RETROSPECTIVE: The King of Elfland’s Daughter by Lord Dunsany

Monday , 13, April 2015 Appendix N 2 CommentsFirst published in 1924, Lord Dunsany’s The King of Elfland’s Daughter was rescued from obscurity by Lin Carter’s work with the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. It was an excellent choice for that project, too. Here we find the forgotten themes that set up the cadence of twentieth century fantasy literature. Here we have a take on elves, trolls, and witches far different from anything on the shelves today. Here we have an undiluted synthesis of the fantasy elements that echoed on into the stories we read growing up. It’s breathtaking in its own right, but being exposed to it somehow makes later, more well known literature snap suddenly into focus due to their shared connection to forgotten lore.

Take for example the way that time is treated as a recurring theme up to about midway through the twentieth century. It seems to behave in rather a strange fashion in Lothlórien where the fellowship of the ring “could not count the days and nights that they had passed there.” And children returning to Narnia could never tell for sure just how much time would have passed there while they were away. In the book Three Hearts and Three Lions, Holger Carlsen’s quest would have ended in disaster if he had gone in to Elf Hill, where “time is strange.” Fantasy since then has gradually developed into something that tends to be much more naturalistic– as if “realism” were now somehow integral to the genre. Something like the Game of Thrones series lacks these sorts of time-related elements altogether.

But Lord Dunsany’s “Elfland” combines these ideas into even broader, more fantastic strokes. Time simply doesn’t exist there. Were a mortal to lose a decade of their life somehow, an elf wouldn’t even begin to know how to sympathize. And they, in turn, not having first hand knowledge of anything having to do with aging could not easily come to terms with the potential for losing their strength or their beauty to the “harshness of material things and all the turmoil of Time.” Indeed, even its most mundane consequences are liable to overwhelm them:

Orion slept. But the troll in the mouldering loft sat long on his bundle of hay observing the ways of time. He saw through cracks in old shutters the stars go moving by; he saw them pale: he saw the other light spread; he saw the wonder of sunrise: he felt the gloom of the loft all full of the coo of the pigeons; he watched their restless ways: he heard wild birds stir in near elms, and men abroad in the morning, and horses and carts and cows; and everything changing as the morning grew. A land of change! The decay of the boards in the loft, and the moss outside in the mortar, and old lumber mouldering away, all seemed to tell the same story. Change and nothing abiding. He thought of the age-old calm that held the beauty of Elfland. And then he thought of the tribe of trolls he had left, wondering what they would think of the ways of Earth. And the pigeons were suddenly terrified by wild peals of Lurulu’s laughter. (Chapter 22)

Elfland is not just timeless, though; it is also elusive. The “friends of Narnia” in C. S. Lewis’s tales never know when or how they will find a way in as the means of travelling there changes with each adventure. In Tolkien’s lore, Eärendil’s finding of Undying Lands is a positively mythical accomplishment. Lord Dunsany’s take on this is much closer to what Poul Anderson did in Three Hearts and Three Lions. The place of the elves is an actual region that exists on the borders of the “the fields we know.” Unicorns stray out of Elfland occasionally just as our foxes skirt the “frontier of twilight” between the two worlds. Strangely, the mundane people that live nearby don’t even seem to be aware that anything even exists in that direction:

And then Alveric began to ask him of the way, and the old leather-worker spoke of North and South and West and even of north-east, but of East or south-east he spoke never a word. He dwelt near the very edge of the fields we know, yet of any hint of anything lying beyond them he or his wife said nothing. Where Alveric’s journey lay upon the morrow they seemed to think the world ended. (Chapter 2)

Just because you have found it once, it does not mean that you will necessarily be able to do so again:

When Alveric strode away and came to the field he knew, which he remembered to be divided by the nebulous border of twilight. And indeed he had no sooner come to the field than he saw all the toadstools leaning over one way, and that the way he was going; for just as thorn trees all lean away from the sea, so toadstools and every plant that has any touch of mystery, such as foxgloves, mulleins and certain kinds of orchis, when growing anywhere near it, all lean towards Elfland. By this one may know before one has heard a murmur of waves, or before one has guessed an influence of magical things, that one comes, as the case may be, to the sea or the border of Elfland. And in the air above him Alveric saw golden birds, and guessed that there had been a storm in Elfland blowing them over the border from the south-east, though a north-west wind blew over the fields we know. And he went on but the boundary was not there, and he crossed the field as any field we know, and still he had not come to the fells of Elfland. (Chapter 10)

But the border between the worlds is capricious and the Elf King can actually cause it to recede in order to prevent people from finding a way into his land:

Then the Elf King rose, and put his left arm about his daughter, and raised his right to make a mighty enchantment, standing up before his shining throne which is the very centre of Elfland. And with clear resonance deep down in his throat he chaunted a rhythmic spell, all made of words that Lirazel never had heard before, some age-old incantation, calling Elfland away, drawing it further from Earth…. So swiftly that spell was uttered, so suddenly Elfland obeyed, that many a little song, old memory, garden or may tree of remembered years, was swept but a little way by the drift and heave of Elfland, swaying too slowly eastwards till the elfin lawns were gone, and the barrier of twilight heaved over them and left them among the rocks.

And whither Elfland went I cannot say, nor even whether it followed the curve of the Earth or drifted beyond our rocks out into twilight: there had been an enchantment near to our fields and now there was none: wherever it went it was far. (Chapter 14)

This is utterly fantastic– exactly the sort of outright magic that was deliberately set aside as fantasy developed from the Tolkien pastiches of the eighties on to the more “grim dark” style of today. And though people borrow from Tolkien all the time, they rarely borrow these particular elements.

Lord Dunsany’s work really is something else, though. The “desolate flatness that stretched to the rim of the sky” that Alveric finds in the place where he’d hoped to find Elfland is stunning. His half-elven son’s ability to hear the horns of Elfland blowing at eventide is… well… it’s positively fantastic. But there is one other ingredient here that further heightens to distance between our world and that of Elfland. You see this plainly in Poul Anderson’s fantasy where Christendom and Elfland are diametrically opposed to each other– even going so far as defining the opposite ends of what would become the Dungeons & Dragons law/chaos alignment spectrum.¹ This is far different from the watered down “good versus evil” approach that most people played it as. It originally had more to do with the inherent conflict between the mundane and the magical– between the human and the alien.

You see this opposition forcefully expressed by the Freer:

“Curst be all wandering things,” he said, “whose place is not upon Earth. Curst be all lights that dwell in fens and in marish places. Their homes are in deeps of the marshes. Let them by no means stir from there until the Last Day. Let them abide in their place and there await damnation.

“Cursed be gnomes, trolls, elves and goblins on land, and all sprites of the water. And fauns be accursed and such as follow Pan. And all that dwell on the heath, being other than beasts or men. Cursed be fairies and all tales told of them, and whatever enchants the meadows before the sun is up, and all fables of doubtful authority, and the legends that men hand down from unhallowed times.

“Cursed be brooms that leave their place by the hearth. Cursed be witches and all manner of witcheries.

“Cursed be toadstool rings and whatever dances within them. And all strange lights, strange songs, strange shadows, or rumours that hint of them, and all doubtful things of the dusk, and the things that ill-instructed children fear, and old wives’ tales and things done o’ midsummer nights; all these be accursed with all that leaneth toward Elfland and all that cometh thence.” (Chapter 31)

Tolkien is of course at pains to avoid an explicit reference to this sort of enmity. It is nevertheless present in The Lord of the Rings when Butterbur scolds Frodo for causing a disruption at The Prancing Pony: “We’re a bit suspicious round here of anything out of the way– uncanny if you understand me; and we don’t take to it all of a sudden.” Bilbo’s reputation took a similar hit what with all “outlandish folk” that were dropping by his hobbit hole. Bag End’s a queer place, and it’s folk are queerer.

But there is much more to this than homespun culture or even fear of the unknown. There is a very real divide between elves and men. And there is a theological aspect to it and it would be a mistake to think that Tolkien was unusual in his tendency to fret about these things in his notes and letters. Tolkien might have had his reasons for wanting to tiptoe around this within the context of his best fiction, but Lord Dunsany had no such compunction:

And in those seasons, wasting away as every one went by, she knew that Alveric wandered, knew that Orion lived and grew and changed, and that both, if Earth’s legend were true, would soon be lost to her forever and ever, when the gates of Heaven would shut on both with a golden thud. For between Elfland and Heaven is no path, no flight, no way; and neither sends ambassador to the other. (Chapter 32)

This is almost the exact same estrangement the Elrond faced with the prospect of giving Aragorn his daughter’s hand in marriage. It is a bitter thing, and it is no wonder that he would do this for no less a man than one that could reunite and restore the Northern and Southern kingdoms of Gondor. And yet, the precise relationship of the elves to heaven is not nearly as explicit there as it could be.

Lord Dunsany is willing explore this in depth, however. Instead of simply ending the story with the match being made between man and elf after the fashion of the fairytale romance, we get to see just how extensive the culture clash between Alveric and the Elf King’s daughter really is. The Freer could hardly stand to oversee the espousal in the first place. “I cannot wed Christom man,” he says, “with one of the stubborn who dwell beyond salvation.” (Chapter 14.) But though he did have “rites that are proper for the wedding of a mermaid that hath forsaken the sea,” Lirazel could never quite acclimate herself human ways. She could never “never read wise books without laughter,” she could “never care for earthly ways,” and she could never feel particularly at home. After all, how could the very few years she’d spent among men compare to how “all the centuries of her timeless home” had shaped her?

Their conflicting views of worship would make it all but impossible for them to get along with each other:

And Alveric seeking her in the wide night, wondering what wild fancy had carried her whither, heard her voice in the meadow, crooning such prayers as are offered to holy things.

When he saw the four flat stones to which she prayed, bowed down before them in the grass, he said that no worse than this were the darkest ways of the heathen. And she said “I am learning to worship the holy things of the Freer.”

“It is the art of the heathen,” he said.

Now of all things that men feared in the valley of Erl they feared most the arts of the heathen, of whom they knew nothing but that their ways were dark. And he spoke with the anger which men always used when they spoke there of the heathen. And his anger went to her heart, for she was but learning to worship his holy things to please him, and yet he had spoken like this.

The presence of these sorts of explicit references to Christianity are shocking today, but for these authors, Christian concepts were integral to the very axioms of fantasy. This strikes us as “conservative” today, but their works were in fact revolutionary. Had Sir Arthur Conan Doyle read tales more like those of Tolkien, Lewis, Anderson, and Lord Dunsany, he would not have fallen so for the Cottingley Fairies hoax. The fact that he did indicates that he was very much a product of his times and had a radically different notion of what elvish creatures “actually” would have been like compared to us. But as influential as Tolkien became over the course of the twentieth century, even so his particular take on fantasy would also fade away just as his Third Age gave way to the far less mythical period that followed it. Lord Dunsany makes it clear just how much we’ve lost.

—

¹ See my previous retrospective on Poul Anderson’s Three Hearts and Three Lions for details.

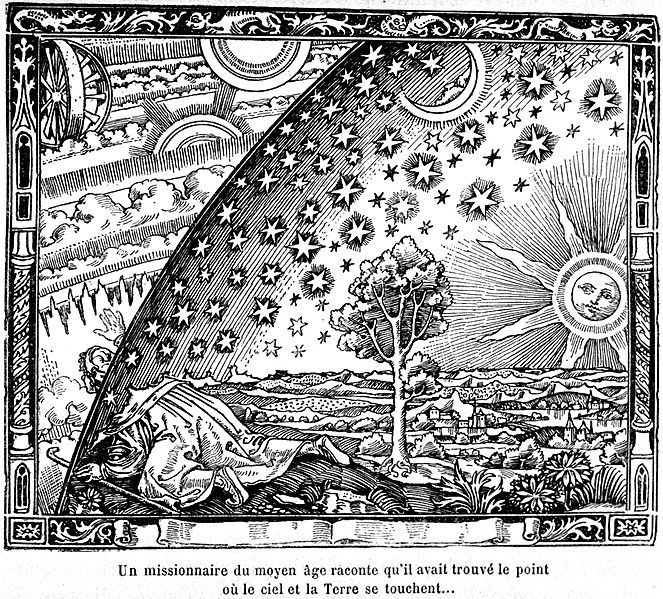

The image of the Flammarion Engraving is from the Wikimedia Commons.

Please give us your valuable comment