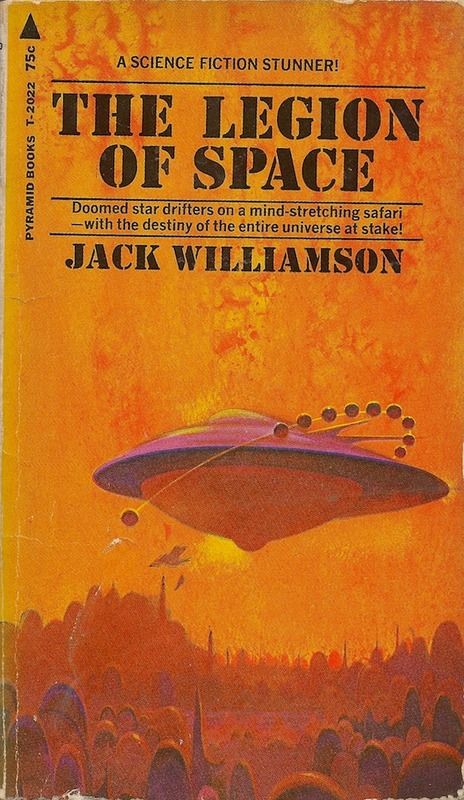

RETROSPECTIVE: The Legion of Space by Jack Williamson

Monday , 24, August 2015 Appendix N 5 Comments Jack Williamson is another one of those names on the Appendix N list that, for too many people, simply doesn’t register as being of any significance. The fact that his career spans eight decades means little now in terms of fame and recognition. That will seem outrageous to some, but I ask librarians and book store clerks about his work and all I get for my efforts is blank stares from them. The same is thing is true for most of the other Appendix N authors with the obvious exceptions of Burroughs, Lovecraft, Howard, and Tolkien, but it’s tough seeing someone of Williamson’s stature treated this way. That he published a novel as recently as 2005 and won a Hugo Award in 2001 doesn’t seem to make the slightest difference.

Jack Williamson is another one of those names on the Appendix N list that, for too many people, simply doesn’t register as being of any significance. The fact that his career spans eight decades means little now in terms of fame and recognition. That will seem outrageous to some, but I ask librarians and book store clerks about his work and all I get for my efforts is blank stares from them. The same is thing is true for most of the other Appendix N authors with the obvious exceptions of Burroughs, Lovecraft, Howard, and Tolkien, but it’s tough seeing someone of Williamson’s stature treated this way. That he published a novel as recently as 2005 and won a Hugo Award in 2001 doesn’t seem to make the slightest difference.

In the early days, he had to get an attorney with the American Fiction Guild to wrangle payments out of Hugo Gernsback. From there he went on to get writing tips from John Campbell. The really big moment for him was when he got a letter from A. Merritt asking to see the carbon copy of his second published story.¹ (The guy just couldn’t wait for the next installment!) He would later become so prominent in the field that he could provide that same sort of kick to someone else: for instance, by sending a postcard to a young Isaac Asimov who was just starting out as a science fiction writer.² If that’s not enough to make clear just how big a deal this guy was, Ray Bradbury declared him to be one of the greats and Arthur C. Clarke would put him on a plane with Asimov and Heinlein.³

I’ve spent a lot of time trying to understand how writers like Fritz Leiber and Fred Saberhagen could go from being nigh unto ubiquitous to being essentially unknown within a single generation, but I don’t have any explanation for Jack Williamson’s lapse into obscurity. It blows my mind. Outside of an increasingly white haired segment of fandom, there is sort of a received wisdom that implies that science fiction essentially got started with “the big three” of Heinlein, Clarke, and Asimov. Except for H. G. Wells and and Jules Verne, just about everything from before them may as well be an undiscovered country. I think more people would want to know what’s out there… but they first have to realize that there’s something there to be rediscovered! Really though, the writers that were just shy of the highest ranks are still quite good.

Cracking open the first novel in Jack Williamson’s first series, we see a snapshot of a medium in transition. Legion of Space was hitting the pulps at about the same time as Stanley G. Weinbaum‘s stories, so the latter’s influence is missing here. Both, however, have moved beyond the single planet focus of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s John Carter stories in order to present a solar system with colonies at just about every conceivable location. While Williamson’s aliens are mere boogeymen not unlike the traditional monsters from War of the Worlds, he does accomplish one thing here that Weinbaum did not touch on: he presents a rather elaborate future history that is precisely in line with the sort of thinking that would serve as the backbone of Heinlein and Asimov’s works.

And while Williamson does present an entirely conventional two-fisted hero that would have been anathema to Lovecraft, he also seems to anticipate another sea-change: an emphasis on a more cerebral scientist type figure as a legitimate hero in his own right. Of course, even as he points to the future of the medium, he continues the Edgar Rice Burroughs practice of framing his tale in such a way that it could actually be a real account:

“Yes, Doctor, I’ve a son.” His thin brown face showed a wistful pride. “I don’t see much of him, because he’s a very busy young man. I failed to make a soldier out of him, and I used to think he’d never amount to much. I tried to get him to join up, long before Pearl Harbor, but he wouldn’t hear of it.

“No, Don never took to fighting. He’s something you call a nuclear physicist, and he’s got himself a nice, safe deferment. Now he’s on a war job, somewhere out in New Mexico. I’m not even supposed to know where he is, and I can’t tell you what he’s doing– but the these he wrote, at Tech, was something about the metal uranium.”

Old John Delmar gave me a proud and wistful smile.

“No, I used to think that Don would never accomplish much, but now I know that he designed the first atomic reaction motor. I used to think he had no guts– but he was man enough to pilot the first manned atomic rocket ever launched.”

I must have goggled, for he explained:

“That was 1956, Doctor– the past tense just seems more convenient. With this– capacity of mine, you see, I shared that flight with Don, until his rocket exploded, outside the stratosphere. He died, of course. But he left a son, to carry on the Delmar name.” (pages 11-12)

(Of course, given the direct mention of Pearl Harbor, it’s clear that this opening chapter could not have been written when the story was first serialized in the thirties. Just as with the opening story in the first Foundation novel, this was written specifically to flesh out the novelization of the old pulp material.)

The action presented here is exactly what George Lucas was going for with the first Star Wars movie: a group of adventurers going from one cliffhanging situation to another in order to rescue a space princess from an alien installation and who must then use her technological MacGuffin power to save the last holdouts of an otherwise doomed rebellion. It’s the fact that the protagonists are all members of the Legion that gives off a more dated feel, though. The reading is almost ponderous at times– there’s no scoundrel character to add spice, no goofy droids to add comic relief, no zen master to add gravitas, and no “farm boy” type for adolescent boys to invest in. Nevertheless, this book’s proximity to earlier works of science fiction seem to lend it an energy which more than makes up for the characterizations.

Phobos is downright scenic, for instance:

John Star had heard of the Ulnar estate on Phobos, for the magnificent splendor of the Purple Hall was famous throughout the System.

The tiny inner moon of Mars, a bit of rock not twenty miles in diameter, had always been held by the Ulnars, by right of reclamation. Equipping the barren, stony mass with an artificial gravity system, synthetic atmosphere, and “seas”of man-made water, planting forests and gardens in soil manufactured from chemicals and disintegrated stone, the planetary engineers had transformed it into a splendid private estate.

For his residence, Adam Ulnar had obtained the architects’ plans for the Green Hall, the System’s colossal capital building, and had duplicated it room for room. But he had built on a scale an inch larger to the foot, using, not green glass, but purple, the color of the Empire. (page 45)

The final climatic moment conveys precisely the same feeling we all felt the first time we saw the Death Star blow up on a gigantic movie screen:

Her voice was perfectly calm, now without any trace of weakness or weariness. Like her face, it carried something strange to him. A new serenity. A disinterested, passionless authority. It was absolutely confident. Without fear, without hate, without elation. It was like– like the voice of a goddess!

Involuntarily, he drew back a step, in awe.

They waited, watching the little black flecks swarming and growing on the face of the sullen Moon. Five seconds, perhaps, they waited.

And the black fleet vanished.

There was no explosion, neither flame nor smoke, no visible wreckage. The fleet simply vanished. They all stirred a little, drew breaths of awed relief. Aldoree moved to touch the screws again, the key.

“Wait,” she said once more, her voice still terribly– divinely– serene. “In twenty seconds… the Moon…”

They gazed on that red and baleful globe. Earth’s attendant for eons, though young, perhaps in the long time-scale of the Medusae. Now the base of their occupation forces, waiting for the conquest of the planets. Half consciously, under his breath, John Star counted the seconds, watching the red face of doom– not man’s now, but their own.

“… eighteen… nineteen… twenty–”

The Moon was gone. (page 186)

No, we don’t get a look at what the consequences of the moon’s disappearance would be on the earth. And this ancient alien menace could be right next door at Barnard’s Star… and which could loot planet after planet for their own diabolical ends: we never find out why it was that they would have left Earth alone for all those millenia when humanity could do absolutely nothing to protect itself!

But no matter. The story ranges from Earth to Mars to Phobos to Pluto to beyond our solar system and back. There are all manner of daring raids and impossible escapes. There is space piracy, treks across alien wilderness, jury-rigged repairs, and A-team style inventiveness. Traveller adventures don’t tend to play out like this… and that’s maybe to their detriment. But the sequence of more or less stand alone puzzle situations presented here is reminiscent of certain strains of text adventure design. There is a great deal of playable gaming material here.

Jack Williamson is not just the author that coined the terms terraforming and genetic engineering.⁴ He played a significant role in helping to move science fiction away from the conventions of planetary romance and on towards a medium of interstellar polities and galactic empires. Looking back at The Legion of Space, it’s hard not to see anticipations of everything from Star Wars to Star Trek to Firefly. But there’s something exciting about going back and seeing what it was like when science fiction writers were having their characters take their first flights outside of the solar system. This is relevant not just to those that want to see how we got to where we are today… but also for those that want to capture again the kind of wonder that we can no longer take for granted.

—

¹ For more on Jack Williamson’s contact with Hugo Gernsback, John Campbell, and A. Merritt, see Larry McCaffery’s excellent interview.

² According to Wikpedia, this is recounted in Jack Williamson’s autobiography, Wonder’s Child: My Life in Science Fiction.

³ According to Eastern New Mexico University’s web site, Ray Bradbury was quoted as saying this in the Los Angeles Times.

⁴ See the SF Site’s Conversation with Jack Williamson for more on this.

Sometimes I wonder if the rocket age stalled out because people stopped reading SF in which the “slow boat from Mars” takes an agonizingly long 7 days to reach Earth.

I need to check, but I THINK I may have the Astounding with The Man From Outside. Wish I had the run that serialized this, though!

Yeah, I like these stories. Fast-paced adventure and Williamson incorporates some really huge ideas in them. I once read a quote from Mark Hamill in which he was talking about how, on the set of Star Wars, he once asked George Lucas where he got all his ideas, and Lucas told him, “From about 400 old science fiction books.” I suspect the Legion of Space books were prominent among those.

I grew up in Portales, where he lived. My mom bought dresses from Blanche, his wife. I once wrote a few chapters of a SF book, and asked him to read it. He was kind enough not to tell me just how bad it was.