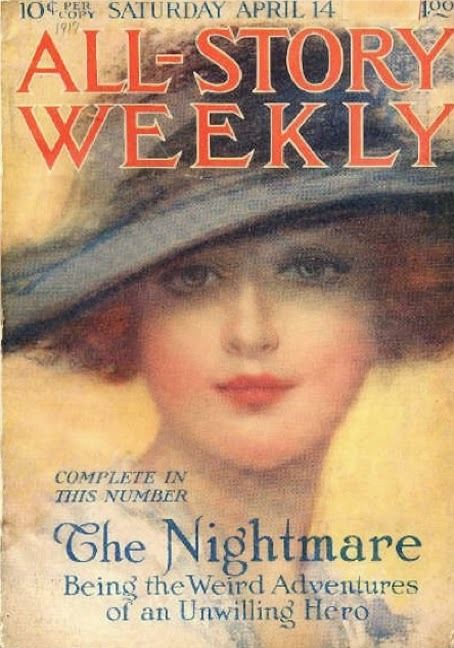

When Andrew Liptak at Kirkus Reviews reported that A. Merritt was influenced by the most significant female science fiction author between Mary Shelly and C. L. Moore, this was something that I had to go see for myself. Merritt produced some of the strangest stories ever made. The chance to see what made his career even possible just seemed like it would be a real treat. And given that Francis Stevens’s “The Nightmare” was published in the year before Merritt would publish “The Moon Pool”, it could very well have played a part in launching his career in “weird” fiction.

When Andrew Liptak at Kirkus Reviews reported that A. Merritt was influenced by the most significant female science fiction author between Mary Shelly and C. L. Moore, this was something that I had to go see for myself. Merritt produced some of the strangest stories ever made. The chance to see what made his career even possible just seemed like it would be a real treat. And given that Francis Stevens’s “The Nightmare” was published in the year before Merritt would publish “The Moon Pool”, it could very well have played a part in launching his career in “weird” fiction.

What’s it like? Well… the most striking thing about this story in this context is its almost total lack of weirdness. Russian princes, bomb-throwing nihilists, and the Lusitania aren’t half as romantic as the lure of lost Incan treasure. Indeed, the real thrills in this piece are downright mundane as often as not– with bits ranging from spontaneously falling stalactites and hastily assembled aeroplanes. The framing device of a nightmare is developed and explained well enough by the end. But with the exception of a recapitulation of a scene from One Thousand and One Nights, there is nothing really mythical tied into the story, nothing of the sweep of evolutionary history, nothing of the flavor of Christian lore, and nothing as alien or remote as the best depictions of fairy.

Even the protagonist is mundane. Rather than a daring man of action that people tend to expect from old pulp stories, the guy is a border-lined coward that doesn’t know how to shoot a gun and that only overcome peril by accident. If you’re the sort to dismiss the entire pulp era as being little more than egregious male power fantasies, then you definitely missed this one. Nowhere does Stevens dis-empower the lead character more than in her handling of the romantic arc.

He ends up looking like a pretty good guy next to his dastardly ally, you might think the guy has half a chance here:

“Believe me, Miss Weston, this charnel odor is no worse than that of the battle-fields to which you were going. I have been there, also. Will you take my arm now? For we must walk through a very disagreeable place.”

“No, thank you!” she–well, she snapped, although it isn’t a nice thing to say of a heroine. “I am sure Mr. Jones will offer all the help I may need.”

This is a woman that knows not only the precise market value of her favors, but also the value men place on the chance to do something for her. And she has no qualms about making it clear to Mr. Jones just what his place in the world really is:

“It is like–it is like a circle from Dante’s Inferno!” exclaimed Jones, laying his hand pityingly on the girl’s arm, and wishing with all his heart that he had never acceded to Sergius’ wishes; that they had left the girl at the caves, or stayed there themselves. What might not the effect of having witnessed such a scene be upon the mind of a delicate, high-strung woman?

But she drew slightly away, and spoke again to the Russian, From first to last she gave Mr. Jones no more attention than one grants to a supernumerary–a necessary adjunct to the play, but scarcely of more human interest than the furniture.

And believe it or not, it goes downhill from there. In a surprise move, she ends up marrying someone she neither flirts with nor rebuffs in the entire escapade:

First I thought it was Paul, and then I thought it was Sergius, only she didn’t want him to know it, and all the while it was Holloway! I’ll bet Miss Weston had Jim Haskins wondering if he wasn’t the lucky one, too. Guess I was the only one not in the running.

Yes, she might swoon once in this story. And by today’s standards, she is strangely eager to distinguish herself by taking on nursing and cooking duties in the adventurers’ camp. But the world this woman seems to thrive on is one of unending courtesies from a whole gaggle of men, each of them competing with the other and potentially coming to blows over the chance to win her favor. Far from being some sort of second class citizen, the impression the various scenes leave is that she is treated like royalty. It’s not so much that she’s a big prize, either– there’s nothing particularly distinguishing about her beyond the fact that she is female. She is just as ordinary as the “hero”, really.

Perhaps the most striking thing about A. Merritt’s work is his depictions of dashing heroes and beautiful, mysterious heroines. Wherever he got the inspiration for that sort of thing, it wasn’t from Francis Stevens– not in this story, anyway. What might he have appropriated in particular? Possibly the whole idea of a lost world as a setting for adventure and romance. But if the lack of more traditional pulp elements weakens the Francis Stevens’s work in comparison to Merritt’s, much more damning is her penchant to leave no mystery unexplained. Indeed, rather than leave a thriving fantasy environment on the outskirts of the known world, she allows her characters to not only loot the place entirely, but also render its unique flora and fauna extinct.

It’s as brutal as the tender ministrations of Miss Weston– and doesn’t leave much to the imagination.

—

Note: The Francis Stevens story from 1918 “The Citidal of Fear” appears to be closer to the style of a good A. Merritt story. We’ll investigate that one in a later installment.

I confess I’ve never read Francis Stevens, though she had a certain standing in SF circles in the 1940s and early 1950s — three of her novels were reprinted in Famous Fantastic Mysteries in 1941-42, and The Heads of Cerberus (possibly not available for FFM, as it was serialised in The Thrill Book rather than a Munsey magazine) was reissued by a fan press in 1952. Cerberus sounds much the most interesting of her works to me, so I’ll be interested to see what you think of it if you decide to read it.

As to being the most significant female SF writer in the century between Mary Shelley and C.L. Moore, I’d have thought objectively that crown was worn by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, though she has the distinct advantage of a utopian studies audience.

I have to say that I think I’ll skip Ms. Stevens. Plenty of other stuff to read.