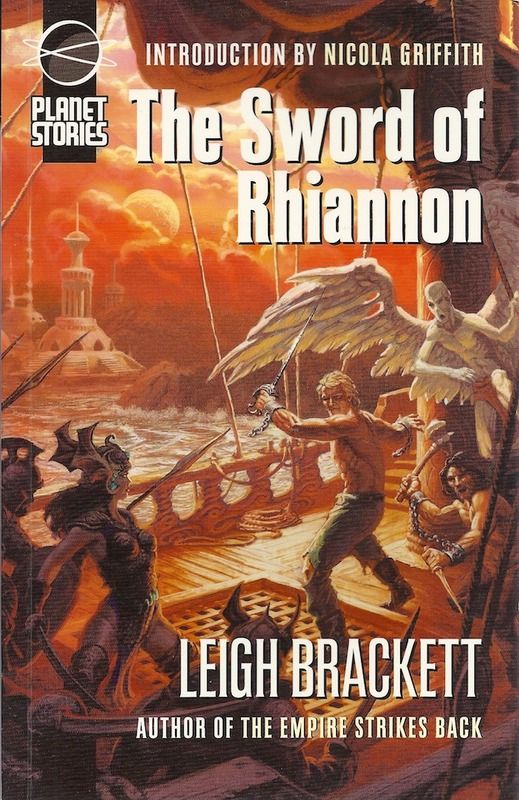

RETROSPECTIVE: The Sword of Rhiannon by Leigh Brackett

Monday , 15, June 2015 Appendix N 13 CommentsThis book is just plain good. As far as I’m concerned, Leigh Brackett’s work can sit on my shelf in a place of honor right beside the work of A. Merritt and Edgar Rice Burroughs. And I’m not the only person that’s had that reaction. Ace actually thought this novel was good enough to run opposite of Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Conqueror as part of their classic “Doubles” line. That’s a tough act to have to follow, but Brackett really pulls it off.

Reading this book it becomes clear just how much the top blockbuster movie franchises owe to the pulp era. Protagonist Matthew Carse, ex-fellow of the Interplanetary Society of Archeologists, makes for a very credible Indiana Jones figure. In fact, the basic outline of the story here is a wild search for the Martian equivalent of the Ark of the Covenant. And given that Brackett had a hand in developing the plot of the first Star Wars sequel, it’s no surprise that themes of redemption play a prominent role here as well. It’s shocking to think how influential she must have been. If you passed over the pulps because you thought they would read like a bad episode of “Lost in Space”, then you’ll be in for a pleasant surprise. If you’re short on cash, don’t look, though. Once you read one Leigh Brackett work, you’ll want more. And you’re liable to watch all the movies that she had a hand in as well– classics like The Big Sleep and Rio Bravo.

Leigh Brackett’s writing is lean and savvy. She knows how to hook a reader and hold their attention. The action never lets up. Everything that’s introduced ends up getting leveraged later. Everything that ends up being important is well established by the time it takes center stage. She has a knack for understanding and conveying the key emotional beats of the narrative. More than any other writer from the Appendix N list, her work reads as if it were a fast paced movie script in novel form.

It’s the characters that really get me, though. The rascally Boghaz plays a similar role as Sallah from Raiders of the Lost Ark. If you recall, he was the good-natured “best buddy” character that provided a sense of camaraderie along with his comic relief. Boghaz is almost precisely of that archetype:

Presently Boghaz found an opportunity to whisper to Carse. “They think now we are a pair of condemned thieves. Best let them think so, my friend.”

“What are you but that?” Carse retorted brutally.

Boghaz studied him with shrewd little eyes. “What are you, friend?”

“You heard me– I come from far beyond Shun.”

From beyond Shun and from beyond this whole world, Carse thought grimly. But he couldn’t tell these people the incredible truth about himself.

The fat Valkisian shrugged. “If you wish to stick to that it’s all right with me. I trust you implicitly. Are we not partners?”

Carse smiled sourly at that ingenuous question. There was something abut the impudence of this fat thief which he found amusing.

Boghaz detected his smile. “Ah, you are thinking of my unfortunate violence toward you last night. It was mere impulsiveness. We shall forget it. I, Boghaz, have already forgotten it,” he added magnanimously. (page 53)

What a guy!

A casual reader might think that this is just Brackett’s take off on A Princess of Mars. And it does owe a great deal to that book, no doubt. But as far as the storytelling is concerned, the tale we get here is much more in line with A. Merritt’s oeuvre. The main thrust of the plot here concerns a high stakes gamble in which a possessed hero has to enter into a romance with an evil space princess in order to accomplish his objectives. While this trope has long since been retired from everyday use, it can nevertheless produce an unparalleled amount of sultry, pulpy drama. And while fans today might have difficulty accepting this sort of premise, I believe that Brackett succeeds in making it work as well or better than anybody:

“Sit down,” said Carse, “and drink.”

Ywain pulled up a low stool and sat with her long legs thrust out before her, slender as a boy in her black mail. She drank and said nothing.

Carse said abruptly, “You doubt me still.”

She started, “No, Lord!”

Carse laughed. “Don’t think to lie to me. A still-necked, haughty wench you are, Ywain, and clever. An excellent prince for Sark despite your sex.”

Her mouth twisted rather bitterly. “My father Garach fashioned me as I am. A weakling with no son– someone had to carry the sword while he toyed with the scepter.”

“I think,” said Carse, “that you have not altogether hated it.”

She smiled. “No. I was never bred for silken cushions.” She continued suddenly, “But let us have no more talk of my doubting, Lord Rhiannon. I have known you before– once in this cabin when you faced S’San and again in the place of the Wise Ones. I know you now.”

“It does not greatly matter whether you doubt or not, Ywain. The barbarian alone overcame you and I think Rhianon would have no trouble.”

She flushed an angry red. Her lingering suspicion of him was plain now– her anger with him betrayed it.

“The barbarian did not overcome me! He kissed me and I let him enjoy that kiss so that I could leave the mark of it on his face forever!”

Carse nodded, goading her. “And for a moment you enjoyed it also. You’re a woman, Ywain, for all your short tunic and your mail. And a woman always knows the one man who can master her.”

“You think so?” she whispered.

She had come close to him now, her red lips parted as they had been before– tempting, deliberately provocative.

“I know it,” he said.

“If you were merely the barbarian and nothing else,” she murmured,” I might know it also.”

The trap was almost undisguised. Carse waited until the tense silence had gone flat. Then he said coldly, “Very likely you would. However I am not the barbarian now, but Rhiannon. And it is time you slept.”

He watched her with grim amusement as she drew away, disconcerted and perhaps for the first time in her life completely at a loss. He knew that he had dispelled her lingering doubt about him for the time being at least. (pages 132-133)

There’s a reason why the genre is referred to as “planetary romance.” And yes, if you were going to make a trashy romance novel targeting an audience that’s made up largely of adolescent boys, then this is how you do it.

Of course, the best days of this type of story are long gone by now. It was practically ubiquitous up through the sixties… but today it’s shocking to see it delivered with not even a hint of snark or irony. Mentioning the very idea this sort of thing in mixed company is liable to produce a whole raft of negative responses. We live for the most part in a culture that is primed to turn up their noses at this stuff.

Now, I eat this stuff up. It is by far among my favorite things about the Appendix N list. I have been vaguely dissatisfied with movies and novels for decades now, but I could never explain to you why. And maybe I missed something, but I’m telling you… we are now as a culture so vigilant about suppressing this sort of story that before I started reading these old books like this, I couldn’t even imagine that stories like this could exist. Which leads to the question of just how exactly did we get from Leigh Brackett to… I dunno… Mad Max: Fury Road.

Well it’s been a long and winding road, that’s for sure. It all started I guess about the time fans of comic books began self-consciously denouncing a good chunk of their favorite medium as thinly veiled “male power fantasies”. People acted as if they needed some kind of excuse or cover to indulge in such guilty pleasures. This transitioned to a point where, say, Galaxy Quest (1999) could relentlessly lampoon Captain James T. Kirk’s propensity to turn the tables on space-faring femme fatales.

There was a dim echo of this sort of shtick cropping up in the 1996 film Star Trek: First Contact, but you really don’t see it much anymore. I mean I give them credit for trying, but I have to say it loses something seeing this sort of thing play out between a nervous android and and mass murdering cyborg sociopath. Even something as aggressively pulpy as 2004’s Chronicles of Riddick carefully sidesteps the issue. Indeed, the “strong female character” presented in that property seems to conflate both the “best buddy” figure and the “love interest” in one stroke. Consequently, the film simultaneously loses both a sense of romance and camaraderie. As entertaining as it might have been, I can’t help but feel that it’s missing something.

Meanwhile there’s no shortage of hand-wringing over the fact that boys just tend to not read as much anymore.¹ There’s all sorts of speculation in the press about what might account for that and what might be done about it. But somehow… no one ever seems to mention the fact that we’ve spent decades collectively ridiculing the sort of books that boys have traditionally enjoyed. The fact that they have largely just quit reading altogether doesn’t surprise me in the slightest.

—

¹ Robert Lipsyte’s Boys and Reading: Is There Any Hope? from The New York Times Sunday Book Review would be just one example of this sort of thing.

Leigh Brackett is like the sci-fi equivalent of rough sex followed by a Kent Cigarette: You’ll come for the filter, but you’ll stay for the taste!

I read many of these “retrospectives” back in the 60’s and 70’s when they were “re-discovered” the first time. Seeing the enjoyment in your words brings back the wonder I felt when I first read them….

Combine this vague sense of decades of decline in blue SF with the coup quotes from prominent editors in the 1990s…editors who are still very much leading figures today, and it is no wonder that the boy barbarians are at the (gamer)gates…

What a great choice!

I still have a copy of a book called ‘Sea Kings of Ancient Mars’. It a thick, almost exhaustive anthology of Brackett’s best stuff. I bought it on my honeymoon from a used bookstore in Hamilton, Bermuda. I love that book.

I read Brackett’s 1st draft of Empire Strikes Back, and it was very tight and focused. From what I can tell, it provided the framework whereby Lucas’ big iconic moves and surprises actually make sense.