RETROSPECTIVE: The Warrior of World’s End by Lin Carter

Monday , 27, July 2015 Appendix N 5 CommentsLin Carter is better known for editing the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series, but this volume from 1974 is anything but a backward glance at the forgotten classics of fantasy. Rather than a mythic past, this tale is set in a far future where the twentieth century isn’t even a dim memory. And though this volume came too late to have an impact on the development on the earliest iteration of Dungeons & Dragons, nevertheless the strange group of quirky protagonists presented here is immediately recognizable as a group of player characters from a role-playing game.¹ This is basically gaming fiction from a time when gaming as we now know it really didn’t exist yet!

The title character is a Construct, a super-strong “hero” type prematurely set loose from a Time Vault. (And note that we never find out about the peril which was foreseen by the Time Gods and which he was created to forestall.) His Illusionist mentor might well have been the reason why AD&D included that specialized variant of the magic-user class. And the knightrix is right in line with seventies era depictions of both Red Sonja who first appeared in 1973 and Power Girl who debuted in 1976 even though she is occasionally consumed with an overwhelming desire to go shopping. But more than any other Appendix N book, this feels exactly like the implied setting of AD&D. Not only are there vast stretches of wilderness with all manner of unruly humanoid races warring amongst themselves, but there are all manner of domain-like entities competing with one another as well. It’s such a perfect fit for tabletop gaming it’s almost uncanny.

As wild and chaotic as the setting might be, there is nevertheless a single language that these divers cultures and monster groups can converse through:

The naked creature, who certainly appeared manlike, did not seem to understand the language spoken by the periaptist. This in itself was odd, for the same universal tongue is spoken across the length and breadth of Gondwane. And, since the land surface of Old-Earth’s last continent in this age totaled sixty-million square miles– shared between one hundred and thirty-seven thousand kingdoms, empires, city-states, federations, theocracies, tyrannies, conglomerates, unions, principates, and various degenerate, savage, barbarian or Nonhuman, hordes, all holding the same language in common– you could spend a lifetime of journeys without encountering a sentient creature speaking an unfamiliar language. (pages 14-15)

Game groups that would prefer to hand-wave the languages of the monster tribes in their campaign in favor of a universal “common” tongue have in this book a literary antecedent to justify their decision. And for those that chaff against the sort of human dominated world that Gary Gygax had in mind when he added severe level limits to demi-human classes in AD&D, this book provides a look at the kind of setting he might have been trying to avoid:

In these, commonly believed to be the Last Days, trueborn humanity was a dwindling, perhaps a dying species. Evolution had continued its subtle, invisible surgery amid the gene pool of Terrene life-forms, and many new races of beasts as well as sentient humanoids had arisen to challenge Man’s dominance of the Last Continent in the Twilight of Time. The Pseudowomen of Chuu were but the most harmless of these curious and often inimical creatures; the Halfmen of Thaad, the Death Dwarfs, the mobile and perhaps sentient Green Wraiths, the Strange Little Men of the Hills, the Tigermen of Karjixia, the Talking Beasts, the Stone Heads of Soorm, and many another breed shared the supercontinent with True Men, and often on an even footing. (pages 18-19)

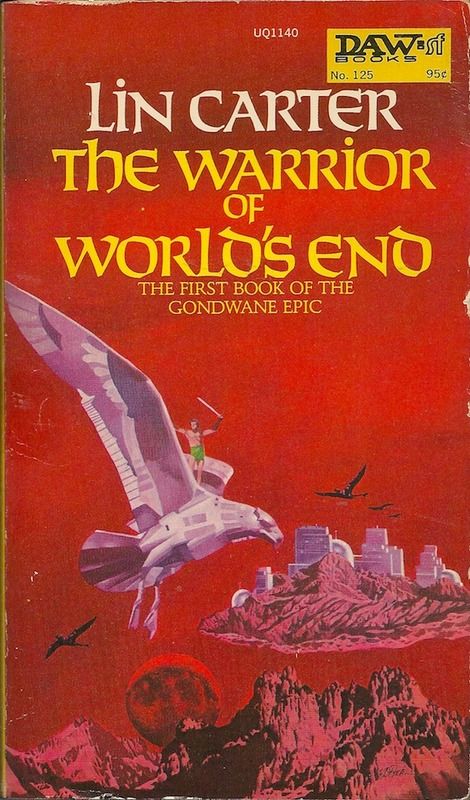

Despite the superficial similarities, this doesn’t really feel like TSR’s Gamma World. There are irreplaceable flying bubble cars that are de facto relics even though they were in production a mere generation ago. One kingdom has the resources to outfit its warriors with crystal armor and electric swords. But there is a uniqueness to most of the artifacts depicted here– as if they were generated by magical engineering rules rather than pulled from canned equipment lists. For instance, the brass Bazonga bird on the cover would count as a golem in most D&D campaigns even though its the ultra rare gravity reversing element yxium which makes it possible for her to fly.

This really is a great premise for a game, though:

You see, there was once a time when all of human civilization had been reduced to one small country, the Thirteenth Empire it is called. It was almost the Last Empire, because except for Grand Velademar all the rest of Gondwane was a savage wilderness where dangerous beasts and wild, uncivilized Nonhumans fought each other for supremacy. When the Thinker was released from his Time Vault, at a place called Aopharz, the end of the world was only a thousand years away. A barbarian horde was arising in Farj and Quonseca; in time it would sweep across Gondwane, trampling the Thirteenth Empire into the dust, slaying or enslaving the last True Men. This could have been the extinction of mankind; at the very least, it would have meant the end of our civilization. (pages 58-59)

With human civilization being reduced to a single polity, there is no shortage of trouble to be found. However, the fact that there are so few superpowers in this setting means that the foes are at a scale where even a small group of individualistic adventurers could really make waves on the campaign map. Change out several of those Nonhuman domains for thinly veiled Vikings, Teutons, and Anglo-Saxons and you pretty much have something pretty close to a good chunk of the active D&D campaigns from the past four decades!²

For people looking for inspirations for making a fantasy setting that feels different from that of Medieval Europe, Lin Carter shows a world where the “Godmakers” cannot keep up with the demand for the new and the different:

A barbarian chieftain from the Largroolian plains desired a new godling with thirteen heards, each more hideous than the last, and the whole carved from a single block of ongga wood twenty feet high; for that order, Phlesco billed the tribe for five hundred ounces of glelium. A shaman from the community of hermits who inhabited fumaroles in the peak of Mount Ziphphiz in Garongaland commissioned him to create to create a god of the winds and the airy spaces which should be as light as air itself, but durable as steel. Phlesco executed the commision by shaping an immense bubble of blown glass filled with helium, the glass impregnated with strands of boron twelve molecules thick and ninety million long, an thus unbreakable. For that, his fee was princely….

Each Godmaker had his own specialty, and none had cause to resent the success of another; Old Galzolb, for instance, tended to execute colossuses, his principal achievement having been to carve an entire mountain into the form of the Sleeping God of Xoom in his youth; sprightly, affable Izzilp, on the other hand, sculpted gods in miniature, and once reproduced the entire pantheon of the Zul-and-Rashemba mythos on one side of a single pearl….(page 21-22)

This is a truly pluralistic setting as far as religion is concerned; each tribe has wildly different mythologies, cosmologies, and beliefs. It’s downright raucous compared to most fantasy treatments of the topic, many of which seem to assume that religion is largely benevolent, private, and separated from government. Other fantasy religions are little more than watered down versions of the Greek pantheon– which tends to be so unsatisfactory that people will react against it by either using real world religions or else eliminating religion entirely.

In contrast to this, Lin Carter could have a little fun with topic. (The moral panic that held sway over gaming in the eighties was nowhere in sight when he was writing, after all.) When the protagonists show up to a strange city, they are all forced to wear huge pink on asparagus-green signs that say this:

BEWARE, O YE FAITHFUL!

THE WEARER BE AN ATROCIOUS IDOLATOR

OF FALSE GODS AND INTERDICTED CULTS

APPROACH HIM/HER/IT AT YOUR SOUL’S PERIL!

When things get out of hand, there are the inevitable trumped up charges:

“The male creature is guilty of Tabard Discarding, Interruption of Priestly Duties, Disturbance of the Civic Tranquility, Ecclesiastical Assault, Defiance of the Peace Monitors, Unwarranted Flight, Theft of Hierophantic Property, and Exceeding the Speed Limit,” droned a bored Justiciar. “The female, already adjudged guilty of Lapsed Conversion, is newly guilty of Resisting Chastisement, Ecclesiastical Assault, Defiance of the Peace Monitors, Unwarranted Flight, Maintaining a Dangerous Confederate, and in aiding and abetting each of the nine points of Unlawfulness whereof her accomplice has just been adjudged guilty. The case is closed; the culprits are to be sold into slavery for the Public Good.” (page 96)

At the other extreme, Lin Carter presents a man who has made himself a God. Admittedly, this is an old story going back at least as far as Alexander the Great. But there’s something different about it when it’s combined with drug addiction and an array of fantastic futuristic artifacts:

The Elphod was there in all his wrath, moonsilver glittering on his golden armor. An aerial chariot drawn by a dozen Phlygûl had borne him to the scene of battle. He stood erect, thundering imprecations in a mighty voice…. In his right gauntlet the Ephod clutched a curious weapon. A rod of shimmering crystal, it was, terminating into a coppery cup. And that cup held a blazing sphere of naked energy. (page 146)

The guy’s no slouch, either. He’s like a James Bond villain that has actually been able to get away with his world domination schemes for decades. From his city in the sky, he extorts money from the nearby Tigermen. If they don’t pay… he’ll steal their air!

This is not exactly a lost masterpiece of classic fantasy, but the fact that it’s eminently suited to tabletop role-playing makes this volume stand out from the pack. And between the map and the glossary, it’s already half way to being a playable rpg supplement just as it is. If you are looking for something to help you break out of the rut of habit and tradition, then this volume makes for an inspiring contrast to the more derivative works that flooded the market in the decades after its release. If you’re looking for a fresh way to frame up the implied setting of classic D&D, however, then this book will be a goldmine. It doesn’t surprise me at all that Gary Gygax would have included it on his list of inspirations.

—

¹ They really could pass for a set of iconic characters for GURPS Fourth Edition.

² In REVIEW: Points of Light, James Maliszewski says that this style of play has “been a setting assumption of D&D from the start.”

I’d forgotten that I read and enjoyed this novel until you reminded me. I’ve always had a suspicion that the Lin Carter influence on the Lancer Conan books was responsible for the more enjoyable of those pastiches.