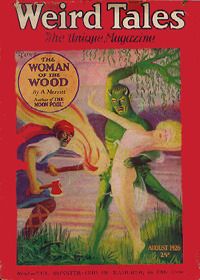

RETROSPECTIVE: The Woman of the Wood by A. Merritt

Friday , 8, April 2016 Appendix N, Before the Big Three 1 Comment Anne M. Pillsworth and Ruthanna Emrys over at Tor.com have covered A. Merritt’s “The Woman of the Wood” and their reaction is I think indicative of just how far contemporary fantasy has strayed from the older styles. They look at this story and they have no idea how to categorize it. It’s that different from anything they’d expect. What’s going on with this…?

Anne M. Pillsworth and Ruthanna Emrys over at Tor.com have covered A. Merritt’s “The Woman of the Wood” and their reaction is I think indicative of just how far contemporary fantasy has strayed from the older styles. They look at this story and they have no idea how to categorize it. It’s that different from anything they’d expect. What’s going on with this…?

Well, starting at about the time Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea Trilogy, fantasy began to be more self-contained and even altogether distinct from Earth and its cultures and histories. It hasn’t always been that way. Whether with Dorothy going to Oz or John Carter traveling to Barsoom or the medieval Jirel of Joiry traveling into a weird an hellish place, it was the norm to have a relatively mundane protagonist with a real world origin. But Merritt is reaching even further back into traditional myths and legends here. The bulk of this tale’s premise is consists of a fairy world that is coexistent with the real one, and which requires a form of “witch’s sight” in order to perceive:

A pillar of mist whirled forward and halted, eddying half an arm length away. And suddenly out of it peered a woman’s face, eyes level with his own. A woman’s face—yes; but McKay, staring into those strange eyes probing his, knew that face though it seemed it was that of no woman of human breed. They were without pupils, the irises deer-like and of the soft green of deep forest dells; within them sparkled tiny star points of light like motes in a moon beam. The eyes were wide and set far apart beneath a broad, low brow over which was piled braid upon braid of hair of palest gold, braids that seemed spun of shining ashes of gold. Her nose was small and straight, her mouth scarlet and exquisite. The face was oval, tapering to a delicately pointed chin.

Beautiful was that face, but its beauty was an alien one; elfin. For long moments the strange eyes thrust their gaze deep into his. Then out of the mist two slender white arms stole, the hands long, fingers tapering. The tapering fingers touched his ears.

“He shall hear,” whispered the red lips.

Immediately from all about him a cry arose; in it was the whispering and rustling of the leaves beneath the breath of the winds, the shrilling of the harp strings of the boughs, the laughter of hidden brooks, the shoutings of waters flinging themselves down to deep and rocky pools—the voices of the woods made articulate.

“He shall hear!” they cried.

The long white fingers rested on his lips, and their touch was cool as bark of birch on cheek after some long upward climb through forest; cool and subtly sweet.

“He shall speak,” whispered the scarlet lips.

“He shall speak!” answered the wood voices again, as though in litany.

“He shall see,” whispered the woman and the cool fingers touched his eyes.

“He shall see!” echoed the wood voices.

The mists that had hidden the coppice from McKay wavered, thinned and were gone. In their place was a limpid, translucent, palely green ether, faintly luminous—as though he stood within some clear wan emerald. His feet pressed a golden moss spangled with tiny starry bluets. Fully revealed before him was the woman of the strange eyes and the face of elfin beauty. He dwelt for a moment upon the slender shoulders, the firm small tip-tilted breasts, the willow litheness of her body. From neck to knees a smock covered her, sheer and silken and delicate as though spun of cobwebs; through it her body gleamed as though fire of the young Spring moon ran in her veins.

This is very similar then to the treatment of fairy that you see in Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword. And the strange combination of the alien, the violent, and the allure of the tree people here calls back to the same view of Elfland that infused the works of writers ranging from Lord Dunsany to Margaret St. Clair. It is about as pure of an approach to fantasy that you can get… and yet the reviewers at Tor.com struggle to pin it down. They want to call it a Dreamlands tale, but this story is not a dream. The tree people retain a certain amount of plausible deniability, sure. But they are quiet clearly real. And the protagonist witnesses none of the action while dreaming, nor does he procure any unusual drugs in order to achieve the sort of dream state that might be required to interact with elfin beings.

That so representative a story could be so hard for people to classify today is yet more evidence for the existence of the Appendix N generation gap. Several decades of tales from the last century have fallen so far off of most peoples’ mental maps, people really have no idea of what they are looking at when they finally come across a stray sample. And fantasy from about 1977 on is largely divorced from the type of fiction that preceded it. One thing we can say about today’s critics, however: they are experts in assessing how problematic words like “swarthy” are in whatever context they find them– and they have a keen nose for flushing out anything that even smacks of Madonna/Whore dichotomies. Whether they need some sort of “witch’s sight” to deliver them from that sort of thing is another matter, however.

Appendix N may mark one of the inflection points in our society where Education divorced itself from Morality.

A cautionary tale, more for the Tor reviewers than others.

“Education without values, as useful as it is, seems rather to make man a more clever devil.” – C.S. Lewis

[A statement to which (not ‘witch’) the Tor writers would likely object most violently.]