RETROSPECTIVE: Warriors of Mars by Gary Gygax and Brian Blume

Monday , 18, August 2014 Tabletop Games 12 Comments Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Mars series is astonishingly influential. It played a pivotal role in the genesis of super hero comics and in the creation of the definitive science fantasy blockbuster film franchise. But while its status the common denominator between both Superman and Star Wars is clear when it is pointed out, its role in the genesis of role playing games is somewhat more obscure.

Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Mars series is astonishingly influential. It played a pivotal role in the genesis of super hero comics and in the creation of the definitive science fantasy blockbuster film franchise. But while its status the common denominator between both Superman and Star Wars is clear when it is pointed out, its role in the genesis of role playing games is somewhat more obscure.

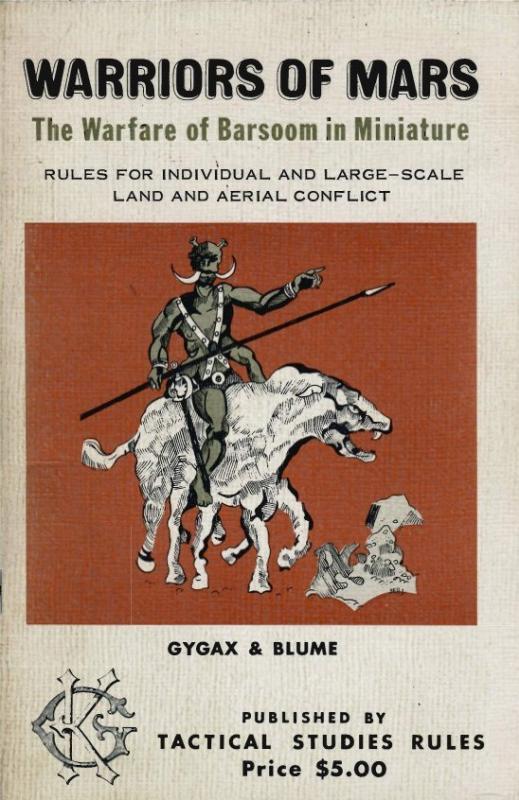

In the forward to the original edition of the first fantasy role-playing game, Gary Gygax put Burroughs as coequal to Fritz Lieber and Robert E. Howard in terms of their ability to capture the spirit of the groundbreaking design.¹ Frankly, the reasons for this are not something that are immediately comprehensible. To find out more, I spent some time investigating this set of miniatures rules for the Barsoom setting which were published in 1974– practically concurrent with TSR’s initial release of Dungeons & Dragons.

The rules for this game are fascinating. They provide not only a window into the sort of gaming that would have been more common at the time D&D’s release, but they also show how Gary Gygax did things at this stage of the game when he could wield creative effort free of the constraints of a dungeon premise and medieval themed fantasy. It can be very difficult to look at any particular aspect of D&D objectively now given just how much play and development the game has received since then. Almost every aspect of the game is wreathed in controversy. These rules are a goldmine because they provide insight into the nature of the game before the juggernaut of fantasy adventure gaming took on a life of its own.

Probably the most compelling aspect of these rules is Gygax himself. When I read his words, there is no doubt in my mind that gaming is just about the most exciting activity in existence. His enthusiasm is positively infectious. More inspiring is his desire to capture a truly epic sweep of conflict on the tabletop:

The essence of Barsoom — the fearless warriors, the men, the monstrous animals, the geography of Burroughs’ Mars, the social customs, the the weaponry — has been formalized into rules which permit the creation of whole new sagas. The tale can be as simple as a minor skirmish between two swordsmen, or it can be as complex as the interactions which arise between several of the Barsoomian city-empires. It can be the lone adventures of a hero pitted against the harsh realities of Martian wilderness, or it can be the epic tale of a voyage of discovery aboard small flier.

The comprehensiveness is astounding. Even if he can’t fit in-depth rules for every single thing that happens in the books, Gygax makes a point to at least touch on just about everything. While some of the material is crude by current standards, the alacrity with which he tackles almost any issue in game design is impressive. Nothing seems impossible. He knows that the rules cannot address everything you could conceivably do to them, so he hands them over to you to develop as you see fit. He treats the reader as more of a custodian of a really great set of ideas than as a mere consumer; he fully expects you continue the design work he’s begun as you make it your own.²

The rules for sieges provide perhaps the most extreme example of this:

Generally speaking they are long and rather tedious affairs, and it is suggested that if they must be conducted the major part be done with paper and pencil. That is, the plan of the city being invested be drawn in triplicate. The defender should indicate his dispositions on one copy, the attacker his earth works and dispositions on another, and a referee keep track of both on the third copy. Attempts to escalade, breach a wall, or whatever can then be worked out by the referee, and the opponents informed of the results. Only when a successful foothold has been gained atop a wall or in a breech should play go to the table top.

This is marvelous and stupid and fascinating all at once. It’s marvelous because it demonstrates an incredible method for creating a scenario for miniatures rules. It’s stupid because there really is no actual hard specifications or game design addressing the actual point. And it’s fascinating because it indicates that miniatures players of the day were not dependent on pre-developed and painstakingly balanced scenarios. Those guys had no problem completely leaving the scope of the rules. It appears that they took it for granted that gamers could trust their referee– far more than typical role players of today tend to trust their game masters. What a relic!

This theme is further elaborated upon in the section on miniatures campaigns. The single page on the topic suggests researching the books to determine the size of the various city-states and notes that Helium has relatively vast resources at its disposal. It also briefly goes into how one might set up a smaller, non-historical game with each player running a small force and being on equal footing with each other. However, the text states that “campaign features such as recruiting mercenary troops, researching new weapons, spying, and assassination must also be determined by the referee.” If you were expecting more guidance from a tiny five dollar rule book, don’t panic. Campaign rule sets are practically impossible to design anyway:

We have found it to be practically impossible to write really complete campaign rules, for there is always some new feature cropping up or some new idea which a player wishes to try. If the campaign is begun simply, giving only the information noted above, it will function quite well for a few turns. The referee will then be able to handle each new detail as it arises, and a set of house rules for the campaign will quickly and naturally develop.

It’s easy to poke fun at this, but in my experience… this actually is how things really work. If you keep even a relatively simple miniatures campaign going for fifty game sessions, you have no idea where things will end up. You might even need to run a couple of short campaigns just to get an idea of what your group is hankering for. But mainly, to find out what your campaign is really all about, you need to start playing games. Even if you can’t get a set of players to agree to commit to weekly sessions over the course of a year, you can still have one. A lot of people want to wait until every detail is nailed down and every player 100% on board to begin, and as a result… they never get the campaign of their dreams off the ground.

The thing that separates a true campaigner from all the other gamers is their willingness to play games with whoever will play them and then determine the impact on the campaign’s status quo between sessions. This can seem difficult if there’s not a large player base for your particular game or if schedule conflicts make it hard to get together. But you can describe situations to people that aren’t directly involved individually and then fold in their descriptions of their overall strategies and then use your imagination to interpolate the nature of succeeding scenarios. Just like in real wars, other people that don’t call the shots can play out the actual fighting. If all you’re used to is tightly engineered board games that lack this sort of iterative, freewheeling chutzpah you’d be surprised at how every unit, every outcome, and every event takes on new meaning once it suddenly occurs within the context of this sort of ongoing history.

And yeah, everyone will do this differently and there are very few rule sets out there that effectively capture this sort of thing.³ It’s sort of like… well… the way D&D and Traveller game masters choose which subset of their rules they will use, making modifications to them, and adding in new things to them wholesale over time depending on what strikes their fancy and what all going on at the table top ends up rubbing them the wrong way. Some people don’t even play by the rules per se. They play the role playing game that’s emerged in their brain over time and then occasionally season it with chrome from whatever rules the players think is actually being used. Role-playing campaigns and miniatures campaigns have more in common than might first appear.

The way the rules touch on how you can use these rules to adventure in the pits is delicious, though:

It is not readily possible to explain fully herein the method of preparation of labyrinth maps by the referee in order for players to adventure in the pits which form mazes beneath every Barsoomian city, old or new. It is suggested that if the participants find such play desirable they have their referee thoroughly re-read all eleven of the Mars series by ERB and then pick up a copy of DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns (also available from Tactical Studies Rules).

Yeah it’s easy… if you go read all eleven books first and buy another game! In a time when there were literally no supplements available for role playing games, referees were completely dependent on the literature that inspired the games if they wanted a solid resource for ideas and play material. But this small booklet does in fact contain a reasonably playable role playing game, even if it is rudimentary. The basic thrust of the game-play should be all too familiar by now:

The referee must prepare some large-scale maps of various areas of Barsoom, as well as city plans for the deserted metropolises which ring the edges of the dry sea bottoms. On these maps he will indicate the presence of unusual terrain features, Green Martian hordes, animals, strange races, treasures, or whatever he deems applicable. The adventures will then set out afoot, on thoats, or by flyer in whatever direction they wish– without seeing the referee’s maps. He will inform them of what they find along the way, and gradually the adventurers will develop more-or-Less accurate maps of the areas they have traveled. The purpose of these adventures is not simply to map, however. It is to gain fighting ability that individuals risk their lives in the Barsoomian wilderness, for with each successful combat with men or animals, with the acquisition of lost treasure, the individual moves up the levels towards the unreachable plane where John Carter reigns alone!

Random encounter charts with six entries each are provided for six different terrain types, but as if the referee doesn’t have enough to do already, several of the creatures are marked as being UNUSUAL. You have to make those from scratch of course. On the other hand, there are additional tables for providing additional information about the parties of human-like and green martians that the players come across. (Green martians are liable to have noblewoman or a princess as prisoner, so if you’re at a loss for an adventure hook you’re good to go.) Oddly enough there are no “number appearing” ratings for any of these encounter entries, so be prepared to improvise! “Whatever makes for a reasonably fun game session” seems to be the unwritten rule here.

There is a table for checking for surprise that is influenced by the players’ party size. In an interesting contrast to classic D&D, you get lots of “points” (experience, really) for killing monsters, slightly more for capturing them, incredibly high amounts for freeing noblemen and so forth, and a comparatively paltry amount for obtaining treasure. If it was any other game, I would rail against this. (It should be next to nothing for monsters and one-to-one experience points for gold pieces and that’s it!) But I have to say, this is a perfect fit for the source material. And yeah, a first level character that rescues a princess will jump to sixth level immediately.

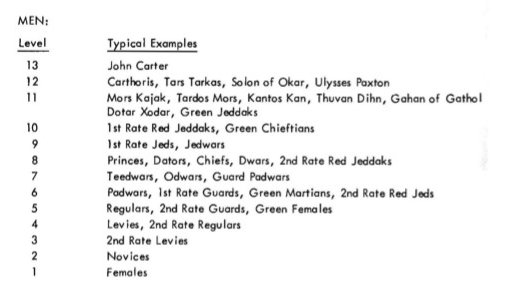

If you’d like to see how someone at the sixth level matches up against characters in the source material, just check this handy chart:

The initiative system given in the miniatures section is particularly interesting as well. Most old hands to tabletop dungeon crawling roll for initiative every turn, sometimes by party and sometimes individually depending on their tolerances for tedium and record keeping. In these rules, the person with the longer weapon attacks first. If each combatant is using a weapon of the same length, then whoever is charging attacks first. Otherwise, the person that elected not to move goes first. These are pretty good rules, but note that they only determine the order of attacks during the melee phases and that’s it. Missiles go first in the sequence of play regardless.

In the 50:1 mass combat rules, movement and formation orders are determined secretly and simultaneously. There’s no advice for how to resolve things when units get closer in, so games at that scale will either require a referee to interpret the orders or (at a minimum) players that can come to a consensus about complicated interactions without slowing down or taking offense.

The miniatures rules become much more playable at the 1:1 scale. The phasing player moves his infantry and resolve their missile fire, all of the non-phasing player’s units move and take their missile fire, and then the phasing player moves his cavalry and resolves their missile fire. After that there is a third missile fire phase that happens simultaneously before the melee round… but note ranged weapons can only fire in two of those phases during the round and javelins can only throw in one.

Combat here doesn’t work anything like what you’d see in a typical role-playing game. The rules assume you’ll have scads of miniatures in formation. There are no die rolls for damage. (!!) A line of red infantry firing bows at some charging green martian cavalry, for example, causes one casualty for each ten bowmen firing. (Note that while short, medium, and long ranges are specified at 1:1 scale in the rules, there is nothing in the charts or elsewhere that defines what difference the different ranges make on combat resolution.) If it takes two turns for the a group of green cavalry to close, those red bowmen will get four shots off. If there were ten of them lined up in a five by two array, they could all fire. (A third rank could join in if they were stations on a hill.)

The randomness comes into play when morale starts getting checked. But even if the green men take 25% casualties, they are simply not going to break if someone like Tars Tarkas is leading them! Lucky for the green cavalry, they cannot lose their personality figure except in melee. Of course, these guys would be within their rights to return fire with bows or even radium pistols according to the Barsoomian code of warfare. Against red infantry, they will deal three or even four times as much damage as they take in return! I can’t imagine those guys fighting under such unfair conditions, so I will assume that they will not use ranged weapons at all.

Assuming that they started with ten cavalrymen, they will be down to six when the two lines connect. The green cavalry will necessarily be in skirmish formation, so we’ll assume that four of them will be facing off against the five front-row red infantrymen. With only one exception, the weapon types involved in a melee do not affect the amount of damage done, only who resolves their damage first! The four green cavalry will each deal three casualties to the green infantry whether their targets have shields or not. But they also get a bonus of two each for charging with a lance. Those four green cavalry can take out twenty infantry before their opponents can even raise their swords!

That should give you a sense of how the rules work. They are somewhat difficult to learn given that there are very few examples in the text, no scenarios, and the charts are in the back completely separated from the sections that explain them. It’s a mess! But they are engineered to allow you to use large numbers of figures and still resolve things quickly. The figures themselves are sufficient for almost all of the record keeping. But given that calots can move more than a yard each turn, you will need a lot of space to play if you put them through their paces.

It is evident, then, that the miniatures rules are basically incompatible with the section on wilderness encounters called “Individual Adventures.” Gygax’s rules for tabletop warfare are built around the assumptions surrounding actual armies even when they are run with scale set to one figure representing one person or monster. This is why Brian Blume’s dueling rules had to be included even though they’re incompatible with all of the other games here. These “Individual Combat Tables” seem to not require a map, so the role playing style combat is more of a “theater of the mind” sort of deal that would be familiar to most people that played the earlier TSR role playing games. They also appear to have initiative rolled by side when they are applied to situations dealing with groups. Also, if someone loses initiative three times in a row, they automatically gain it the next round. (Shades of Monopoly!)

A quick example should get their general flavor across. We’ll resolve a club-wielding white ape that is charging against a third level hero type character that has a javelin and a sword. First, let’s resolve the javelin throw. (Wow, is this chart hard to read!!) If I’m reading this right, it takes a 13+ on three six sided dice to hit this thing… and six total hits to kill it. Higher level characters would have a chance of killing it in a single attack in melee, however a solid hit with a ranged weapon also results in an automatic kill… and even if you’re close you can still score between one and four hits at once. Ranged weapons are really powerful in these rules and are effective even for low-level characters.

A quick example should get their general flavor across. We’ll resolve a club-wielding white ape that is charging against a third level hero type character that has a javelin and a sword. First, let’s resolve the javelin throw. (Wow, is this chart hard to read!!) If I’m reading this right, it takes a 13+ on three six sided dice to hit this thing… and six total hits to kill it. Higher level characters would have a chance of killing it in a single attack in melee, however a solid hit with a ranged weapon also results in an automatic kill… and even if you’re close you can still score between one and four hits at once. Ranged weapons are really powerful in these rules and are effective even for low-level characters.

Unfortunately, our plucky hero rolls a 7 and misses completely with the javelin while automatically giving up initiative for the first round. It takes four wounds to kill a third level man… and the ape (getting a bonus for its club) will wound the man on 7 to 11 and kill him on 12+. (This is not good.) The white ape rolls a 7 and the man takes one wound. The ape wins initiative and tries again. He rolls an eight, so the man takes a second wound. Now the man attacks. He will wound the ape on a 13 or better. He rolls a fifteen, dealing a single wound to the ape. The odds JUST are not good for our hero here. (Checking a different row on the chart, it is apparent that the Level 13 John Carter would not even be breaking a sweat in such an encounter!) Resolving turn 3, he wins initiative over the ape and misses and the ape finally rolls high with a 14. The man is automatically killed even though he could have taken two more “wounds.” Game over!

So then, Blume’s dueling system is relatively quick playing because of it’s built-in chance to kill in a single strike. It’s easier in play due to the lack of damage rolls, but more difficult due to its eye destroying cross-reference chart. However, it does include a system for causing animals to flee when sufficiently frightened– something that would be codified in Traveller’s 1977 animal encounter system. To make the system work in the kind of adventuring campaign indicated in the wilderness section would require the referee to work out a method for the players to gather rumors to determine where challenges were that were on their skill level or else improvise a system that would allow the players to run away if and when they got in over their heads. There is no advice on how to manage that sort of thing here, but those particular issues were often hazy in many early role playing games anyway, so I can’t fault the rules too much for that.

The aerial combat rules represent an entirely different sort of game that is mostly incompatible with everything else here. The flyers are scaled so that they move between about five and eight inches a turn. The sequence of play is not actually hammered out, but the designer suggests either doing secret and simultaneous orders or else a “move-counter-move” system. The thing that Gary Gygax seemed not to realize is that some sort of phased movement like in Star Fleet Battles (1979) or Car Wars (1980) would probably be a much better fit for this type of sub-game.

The aerial combat rules represent an entirely different sort of game that is mostly incompatible with everything else here. The flyers are scaled so that they move between about five and eight inches a turn. The sequence of play is not actually hammered out, but the designer suggests either doing secret and simultaneous orders or else a “move-counter-move” system. The thing that Gary Gygax seemed not to realize is that some sort of phased movement like in Star Fleet Battles (1979) or Car Wars (1980) would probably be a much better fit for this type of sub-game.

The ship specifications are broken down into number and type of guns and their facings, number of bombs and how many can be dropped at once, how much damage the ship can take, what weapons the ship is impervious to, and also the number of gunners, crew, marines, and officers. While there are range bands, damage amounts, and to-hit numbers specified for each weapon type, there are no clear rules that I see that spell out what the exact roll entails. (I would presume that it is a 3d6 roll as it is for most everything else in these rules, but who can tell?) Likewise, there are rules for critical hits, but I do not see under what conditions they take effect. There are also rules for boarding combat that are similar to the earlier miniatures rules, but with a greater emphasis on morale. While these rules do have some examples sprinkled in among them, they do not appear to have gotten the same level of attention as the other sections. Reading them doesn’t make me want to play them– they make me want to complete the design process!

To sum up, then, this is a wonderfully audacious set of rules. Gygax and Blume appear to have completely captured the flavor of the books, and really did deliver on their promises. At the same time, it would be years before this company could produce boxed gaming sets that could conceivably be mastered by people that weren’t already seasoned gamers.⁴ For people that want to adventure on Mars, the encounter charts and experience system provide a head start in helping you rough out a wilderness setting and some objectives.

The real gem, however, is Gygax’s 1:1 miniatures rules. The fact that they allow for massive battles with very little dice rolling is fascinating and looks like something that’s still worth a try today. If you’ve never seen a game built quite in that fashion, you’ll want to at least take a look at it. There’s very little record keeping involved and the miniatures themselves are used to track unit strength or “hit point” factors. I think, though, that the real lesson of these rules lies in how they demonstrate just how much of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Mars stories can translate to the tabletop. And not only that, but how many types of games are implied by the action of his tales. No single game can encapsulate them; it takes several just to begin to capture the scope of it all.

And I think that is Barsoom’s lost legacy to Dungeons & Dragons. The original fantasy role-playing game was never just about delving in dungeons and striking off into the wilderness. It was also about becoming a Lord, establishing a castle, raising an army, and going to war with other powers of the realms. The real difference between role playing games and everything else happening on the tabletop is that you really could go anywhere and do anything. If you really had full autonomy in your ongoing campaign, it should be possible to engage in all kinds of epic battles, not just small scale tactical combat. Just like John Carter on Mars, there’s no reason that the scope of play couldn’t shift back and forth between one-on-one duels to the death in the arena, skirmishes between dozens of combatants, gigantic battles with massive number of troops on each side, and epic aerial battles. And yet something so fundamental to game’s original conception is not only relatively obscure, but for the most part is no longer considered to be an integral part of the game. It doesn’t have to be that way.

—

¹ “These rules are strictly fantasy. Those wargamers who lack imagination, those who don’t care for Burroughs’ Martian adventures where John Carter is groping through black pits, who feel no thrill upon reading Howard’s Conan saga, who do not enjoy the de Camp & Pratt fantasies or Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser pitting their swords against evil sorceries will not be likely to find DUNGEONS and DRAGONS to their taste.” — Gary Gygax in the forward to the original edition of Dungeons & Dragons

² “Still, all games are in a sense fantasy, and games based on fantasy need know no bounds, so play it as you see it, and have fun.” — Gary Gygax in the introduction to Warriors of Mars

³ Car Wars is a tightly designed game by Steve Jackson that was first released in 1981. Even though it allows for both fast paced arena combat and continuing role playing characters, players are left to themselves to determine what the specifications of each scenario in the campaign is going to be. In practice, this turns out to be whatever people are in the mood for, whatever previous sessions indicate is a likely follow up, and whatever happens to exist among the various on hand and relatively tested scenarios. It would be all but impossible to play the game regularly without coming up with a dozen house rules and rules clarifications.

⁴ I’m of course referring to the Holmes Basic D&D Set (1977), the Moldvay Basic D&D Set (1981), and the Mentzer Basic D&D Set (1983) each of which initiated massive numbers of people into the hobby.

I own this book and am not, in any way, astonished (or “strickem with sudden fear”). I think it is useful but do not, in any way, believe it or Burrough’s work to be influential to all but the most old school of gamers.

“All but unknown” might be a better descriptor (rather than “astonishing” or “influential”) to one not given to yellow journalism.

-

I think you underestimate Edgar Rice Burroughs’s significance. He was at least as influential on the genesis of D&D as writers like Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber. For a generation that thinks that Disney’s John Carter was ripping off films that were, in reality, actually inspired by Burroughs’s works, I think his place in gaming really is astonishing. Gary Gygax was not shy about acknowledging his debt to the man. I won’t be shy about it either.

-

“Edgar Rice Burroughs never would have looked upon himself as a social mover and shaker with social obligations. But as it turns out—and I love to say it because it upsets everyone terribly—Burroughs is probably the most influential writer in the entire history of the world.” — Ray Bradbury

I don’t think Burrough’s influence can be overstated, especially taking his whole oeuvre into account, Tarzan, Pellucidar, etc… All the authors I grew up reading grew up reading ERB. And then I read the reprints. Without authors like Vance and Burroughs gaming might be very different. Is today’s average gamer even aware of Burroughs? Maybe not. And that’s fine. But one doesn’t have to be aware of something to enjoy its influence. I’ve never read the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 but its never stopped me from traveling on an interstate.

-

Over at The Black Gate, Ryan Harvey says Edgar Rice Burroughs “re-shaped popular fiction, helped change the United States into a nation of readers, and created the professional fiction writer.” It’s astonishing that an author that influential is now “all but unknown.” Talk about the narrowing of science fiction and fantasy…!

I don’t even notice Jeffro’s yellow journalism anymore. You read one tirade against King Alfonso and you’ve read them all. I think Jeffro holds the Spanish responsible for GDW’s closure in 1996.

-

Free the Expo 67!

I imagine that “Level 1 – Females” is yet another one of those relics like trusting your referee, not the rules, to be both creative and fair.

I think people would be shocked if – at a Warhammer Demo or something – a player staged a siege on another and the first thing they whipped out were sketch pads. The funny thing is, this is exactly how the game was played back then. Our DM’s flipped coins, held lie-telling contests, and even occasionally set fire to things. Pictionary-type resolutions were not out of bounds. Neither were blowtorches and hot wheels for Car Wars sessions (which occasionally morphed into real-time stunts and ramming attempts.)

Some of that had to do with the remnants of young boy games…but some of it had to do with a sense of trust and open gaming. Grown-ups tend to be better players, but there is something to be said for raw enthusiasm.

-

I’d rather play a game I don’t care for with someone that is on fire to play it than do just about anything with someone that isn’t particularly enthusiastic about it.

Car Wars with Barsoomian Air Ships????

Sign me up!

is ripping off the innumerable films inspired by Burroughs — the Barsoom novels were hugely influential for decades. They are, in many respects, the wellspring from which contemporary fantasy and science fiction flow, even if the debt both genres owe to these seminal books is often unacknowledged. Gary Gygax, though, was not shy in acknowledging the debt he owed to Burroughs. He mentioned his name in both OD D and in Appendix N of his

[…] RETROSPECTIVE: Warriors of Mars by Gary Gygax and Brian Blume […]