REVIEW: Domains at War (Battles) by Alexander Macris

Monday , 25, August 2014 Tabletop Games 11 Comments Just looking at the earliest rule books it’s hard to imagine how role playing games really took hold like they did. Many of the first wave of products were nigh inscrutable, poorly edited, and amateurishly illustrated. Sure, what they lacked in polish they more than made up in charm. And as S. John Ross’s Encounter Critical demonstrates, you actually can make a surprisingly good game even when you limit yourself to the most debilitating constraints of the old presentation styles. Nevertheless, there was a lot of unusual things going on at the tabletops of the top designers back then that never got fully translated into the rules or the adventure modules of the day.

Just looking at the earliest rule books it’s hard to imagine how role playing games really took hold like they did. Many of the first wave of products were nigh inscrutable, poorly edited, and amateurishly illustrated. Sure, what they lacked in polish they more than made up in charm. And as S. John Ross’s Encounter Critical demonstrates, you actually can make a surprisingly good game even when you limit yourself to the most debilitating constraints of the old presentation styles. Nevertheless, there was a lot of unusual things going on at the tabletops of the top designers back then that never got fully translated into the rules or the adventure modules of the day.

Probably the most well-known example of this is the whole idea of a megadungeon. These sprawling underworlds made up a huge chunk of what Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson actually ran, but nothing remotely like their home campaigns was ever published.¹ There are many artifacts in the rule books that derive from their style of play that look strange in retrospect. For instance, the fact that Dwarves and Gnomes can “detect sloping passages” seems odd now, but those abilities could make the difference between life and death to parties navigating a massive underground environment.² While it took the better part of a decade for people to translate Gygax and Arneson’s rules into something more readily comprehensible, it would take almost three more before guys like Michael Curtis³, James Maliszewski⁴, and Greg Gillespie⁵ could work out how to design and produce those sort of unusually large dungeon designs.

In a similar vein of lost lore, there’s all the minutia in the AD&D rule books about some sort of elaborate domain level game that is never quite spelled out. It’s rare to hear of anyone doing much anything with it. Just making it to second level in the old games is tough enough, never mind “name level.” But it’s all there. For instance, at 8th Level (110,001 experience points) Clerics gain a significant force consisting of a cavalry types and both heavy and light infantry. At 9th level (225,001 experience points), the Cleric can build a castle at half the normal price and if they “clear a hex” in the surrounding territory they get a monthly revenue of 9 silver per inhabitant. (That’s two more s.p. above the fighter’s rate and four more beyond the magic user’s!) Another perk: all of those men-at-arms are fanatically loyal and work without pay as long as the cleric remains true to his faith.

Compare that to the fighter. He doesn’t start into the domain game until he reaches 9th level (250,001 experience points– much later than the cleric.) The body of men-at-arms that show up are going to be of a single type and they’re nothing more than mercenaries. If they aren’t paid, they go away! (Which makes one wonder just how difficult it is to acquire mercenaries under normal conditions….) The real perk here is the leader that comes along with them– he’ll range from 5th to 7th level and will have some significant magic items to boot. Taken together, this says more about the relative import of the church in the implied setting than it does the actual domain game itself. Fighters are late bloomers and don’t have nearly the same level of cachet. And while only a very few gamers these days can grasp the fact that the varying capabilities at first level are balanced by additional experience requirements for leveling up and varying levels of ultimate potential⁶, we can see that there’s an additional level of balancing between the classes introduced by this additional strata of gameplay.

While Gary Gygax might have labored over these painstaking details, precious little of it ever impacted what happened at the table tops of the wider gaming scene. Based on his design approach in Warriors of Mars, we can safely assume that he thought gamers would just figure something out. Sure, there are a few odd notes about waging mass combat battles to “clear” monsters from a hex and there is information on all sorts of specialists the you could hire for that stage… but there was quite a bit more work to be done developing this aspect of the game. The fact that the design work was incomplete is a huge factor in insuring that this aspect of role playing would be quietly retired and forgotten by large swaths of gamerdom over the course of the eighties and on into subsequent decades.

Things didn’t have to play out that way and we have a lot more options for tabletop gaming today. It’s been a long time coming, but that this aspect of the old game is finally receiving the same sort of attention that megadungeons recently went in for. You see, Alexander Macris’s Domains At War is set up to allow old school D&D characters to take center stage in large battle scenarios that borrow some of the best elements from recent advances in wargame design. While I’m generally a bit more skeptical of anything coming out of Kickstarter these days, in this case Autarch and company really have delivered. We finally have to necessary tools to bring the classic D&D domain game to life.

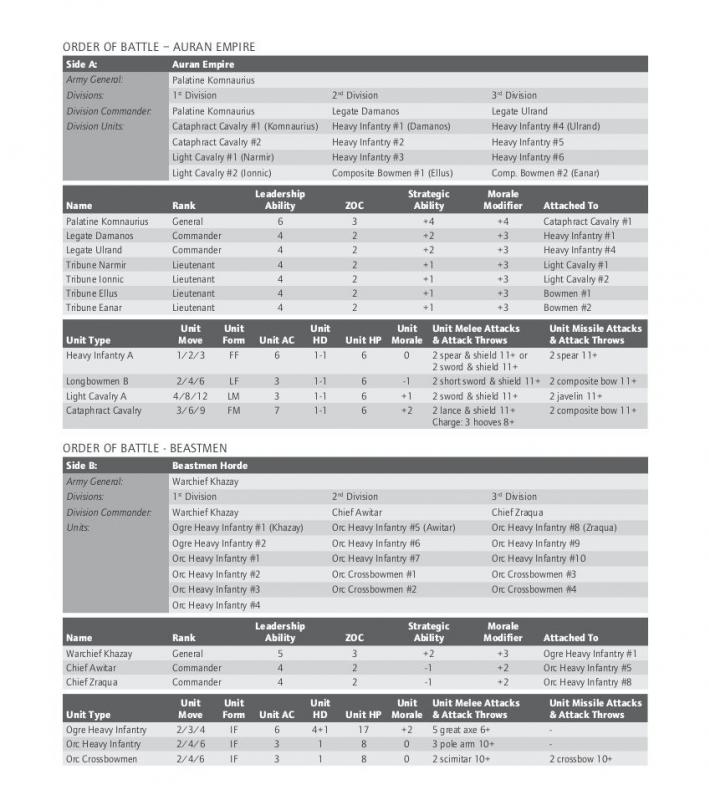

Consider this character rolled up for classic B/X D&D with 3d6-in-order for attributes. STR 15, INT 14, WIS 9, DEX 7, CON 6, CHA 12. Under the rules given in Domains of War this yields an avaerage Leadership Ability of 4 based on the character’s maximum number of retainers which is derived from Charisma. His ZOC is half of that (rounded up) which comes out to 2. His strategic ability is derived from the best attribute bonus of either Intelligence or Wisdom minus the worst attribute bonus of either Intelligence or Wisdom. In this case, that comes out to 1. Finally there is a Morale Modifier which is based on the character’s Charisma bonus, which in this case is zero. This is everything you need to know to let this guy lead an army on the tabletop.

Sure, this character makes a pretty decent fighter. He’s short on hit points, not so good with a bow, and is kind of sluggish and easier to hit than average… but none of that matters in the context of a large battle. With a Leadership Ability of 4 he can lead five or six hundred men into battle and coordinate them about as well as most other leaders. Each point in Leadership Ability allows him to (under normal circumstances) activate one unit of men and move and attack with them. The ZOC of 2 means that he can order units up to two hexes away without penalty. His strategic ability of 1 is used mainly as a bonus on the 1d6 initiative rolls that are made at the start of each turn. Finally, his Morale Modifier of 0 is somewhat underwhelming: he just can’t affort to push his luck overmuch because his unit is far more likely to retreat when it starts making shock rolls and far less likely to rally during morale checks. (Each of these rolls are made on 2d6.) In many flavors of D&D, Charisma is nothing more than a lame dump stat, but as soon as you’ve got five hundred men depending on you, it becomes a very significant dimension of your character’s capabilities, and these rules account for that.

Note that this system assumes the use of some kind of proficiency system on the role-playing side which is absent from the Basic and Expert D&D games I run. This is easily remedied, however. For clerics, I might simply give them a +1 Morale Modifier for every four levels. (And note that clerics with at least average Intelligence are already going to have above average Strategic Ability.) For fighters, I might allow them to take +1 to either Leadership or Strategic Ability every five levels. Halflings might get a single bonus at eighth level, Dwarves at every six levels, and Elves just once at level 10th. All of that would give a significant advantage to the higher level characters while at the same time staying consistent with Gygax’s arcane restrictions on demi-humans that were designed to ensure a tilt towards human supremacy in the default milieu.

I’ve set up a game board so that you can get a general idea of how these rules play. In the picture above, you can see the game’s introductory scenario. (I do not have a set of counters and maps for Domains At War, so please bear with me.) The first thing I notice is that the hex map from Commands & Colors: Ancients is noticeably cramped in this game. Also, units have substantially more hit points than in that other game: the units of the Roman-themed Auran empire all have six hit points each, which puts a bit of a strain on my block stockpile. The orc units (represented by counters from Dragon Rage) each have eight hit points… so using blocks to track each unit’s “health” becomes too unwieldy to bother with there. The ogre units with 17 hit points each are right out! If you are at all enamored with the potential of this game, you will surely want to get the physical counters and markers from the game’s supporting PDF’s⁷ and as large of a hex map as will fit on your gaming table!

Now, the first thing that happened in this game was that the orc commanders all flubbed their initiative rolls. This is not surprising given that the Roman-style commanders all have Strategic Ability bonuses of +2 or higher. Meanwhile, then orc chiefs on the either flank have penalties of -1! The Roman commanders have chosen to allow the orcs to go first, as the human units here have better ranged weaponry and less staying power. The orc and ogre infantry lack ranged attacks altogether and so choose to hustle in, using a slightly faster movement rate. Their infantry can’t engage the enemy this turn, so they might as well move in as quickly as possible.

One thing you’ll notice is that there is one unit hanging back on each of the orc army’s flanks. What happened there is that those two mediocre orc chiefs could only command four units this turn besides the one that they are attached to. They get to command the unit which they’re attached to for “free” if it isn’t disordered, so they could activate a total of just five units and each had to leave an infantry unit behind. While it seems like these orcs should be able to all march right in while keeping their formation, I actually kind of like the fact that they have to deal with this minor hassle due to their deficiencies as commanders. Units lead by heroes with high Charisma just won’t have to put up with this, so while it is maybe “unrealistic” on some level, I like having some kind of tangible consequences for the disorganized “barbarians” that lack that sort of leadership that would be common among the much better organized Roman-type legions. Note that the presence of a tribune or two among the orc units would have completely eliminated this problem for them, but they just don’t have that kind of leadership available.

Also note that the orc crossbowmen on either flank have a chance to shoot directly at the Roman commanders they are facing. Had the orcs had more in the way of ranged attacks, this could have turned out to be devastating to their opponents. The Romans have made an error in setting up: if they had placed even one unit just a bit further ahead, that group would have had to have taken this fire instead. (Ranged attacks are required to always target the closer unit in this game.) Resolving these ranged attack is straightforward. Each orc crossbowmen unit gets two attacks that hit on 10+. Adding in the Armor Class of 6 of the heavy infantry they’re targeting, they need 16+ on d20 to hit. There are no damage rolls in this game: each hit normally does a single point of damage. This might be considered “fiddly” by board game geek standards, but it’s fast compared to many role playing games and easier to learn and teach than most wargames.

Now, here’s a scene from the Roman right flank on the second turn. The legionaries had chosen to “ready to attack” on the first turn. (There is a marker for this in the game’s counter set– not shown here!) This gives them the opportunity to preemptively attack if anyone messes with them. Better yet, this rule allows tougher units to protect their more vulnerable comrades. Say you have some heavy infantry set to “ready to attack” and they are next to a group of longbowmen that have already fired and are practically just sitting ducks there with their lousy armor class rating of three. If orcs choose to charge the bowmen, the heavy infantry can spend its “readiness” marker to both execute a reactive attack and to become the target of the enemy charge.

But the orc’s charge is foolhardy for multiple reasons here. First, they’ve gotten out ahead of their supporting crossbowmen which will require extra Action Point to activate next turn. (They’re more than two hexes away from their chieftain and are thus harder to manage.) Next, they orc infantry have automatically become disordered as a result of this maneuver (marked with a black heart above) which also causes an extra Action Point to be required to activate each unit next turn while also giving them penalties to their shock and morale rolls. The extra attack bonuses that a charge would give them just aren’t worth all of this due to the limitations inflicted by the orc chieftain’s command abilities.

So how do things play out? The orcs charge in and each of their units eats a reactive attack… which does double damage in this case because the Romans have “set spears.” (This is another bonus that’s due to their decision to “ready to attack.”) But that’s not all. The Romans then get their attack for this turn as well. The unit on the far right pictured above has taken four hits as a result of this. This immediately triggers a shock roll on them which is at -2 for their being disordered and another -2 for their being at half hit points. A nine or less in 2d6 here results in that unit to turn tail and flee four hexes towards its side of the board. A six or less would have caused it to route off the board altogether!⁸

This is a complete disaster for the orc army on this side of the board. If the Roman commander here wins initiative on the next turn, they’ll be able to double up their attacks on these two now-isolated forward units that remain. The orcs on this side of the board will then be so discombobulated that they will have a hard time answering back with anything like the same attacking power. Their only hope is to remain around long enough so that the ogre heavy infantry can engage in the center and crush the enemy general. (Their five melee attacks at 6+ are devastating and not to be taken lightly.) This orc chieftain really shouldn’t have charged in like this and he may well have thrown the entire battle: if his units rout, then the orc general in the center stands a good chance of getting flanked!

—

This is only the briefest overview of what’s in the basic game– just enough information to help get you playing as quickly as possible. But I’ve only scratched the surface of what’s in the book. There are terrain rules that leverage the brilliant dice drop mechanic that was pioneered by Zak Smith⁹. (This is really smart actually because setting out the terrain fairly in miniatures games like this is a very thorny exercise if you want it to be be fun, fair, and consistent with the location’s general terrain description.) There are rules for “hero units” that bring individual player characters to the battlefield. There are rules for upscaling to even larger battles and downscaling to platoon level action. There are stats for almost every kind of unit you could want and rules for converting even more from classic style role playing games. There is also a gigantic scenario with a much more elaborate order of battle that looks like it could take all day to play.

This is only the briefest overview of what’s in the basic game– just enough information to help get you playing as quickly as possible. But I’ve only scratched the surface of what’s in the book. There are terrain rules that leverage the brilliant dice drop mechanic that was pioneered by Zak Smith⁹. (This is really smart actually because setting out the terrain fairly in miniatures games like this is a very thorny exercise if you want it to be be fun, fair, and consistent with the location’s general terrain description.) There are rules for “hero units” that bring individual player characters to the battlefield. There are rules for upscaling to even larger battles and downscaling to platoon level action. There are stats for almost every kind of unit you could want and rules for converting even more from classic style role playing games. There is also a gigantic scenario with a much more elaborate order of battle that looks like it could take all day to play.

Never mind all the details though. This game does for mass combat what Steve Jackson did for tactical combat with Melee and Wizard. Even better, the basic system of armor class, hit points, and d20 to-hit rolls will be immediately recognizable to most role-players. It’s great that people that could never be convinced to sit down to a game of Commands & Colors or Dragon Rage will play this, but the fact that it provides a context for martial characters with high levels of Wisdom and Charisma to really make a difference totally seals the deal. This is something I’ve wanted for a long time even if I didn’t quite know it and it addresses a wealth of design issues that emerge in many of the older role playing games. This is a very big deal, an achievement on par with the development of playable megadungeons.

Now, I’ve run D&D sessions that were made up of multiple lightning raids on a dungeon. I’ve run others that consisted of nothing but random wilderness encounters. Other times a session will devolve into a single epic tactical combat that takes hours to resolve. Domains at War opens up mass combat for a similar kind of treatment in the context of wide open role-playing sessions. The fact that each unit on all sides can conceivably be moving and attacking each turn does mean that things will drag for the first couple of turns, but decisive action is possible given the interactions that can occur with flank attacks, shock rolls, morale checks, and loss of commanders. It is this chess-like sudden death phenomenon is was is lacking in many of this game’s competitors.

But this combat system doesn’t have to end up hogging an entire session. I can see these rules being used to make a four hour session that culminates into a smaller one hour mass combat sequence as a climax. The thing that most interests me about it is that it will present a problem to the players that will strongly reward them if they can manage to coordinate their tactics and at the same time punish them severely if they fail to do so. In my opinion, this is the bread and butter of role-playing sessions, and I’m glad to have one more method in my arsenal to make it happen. The fact that commanders are the last to die in a unit also means that epic combat scenarios can be run with a much smaller chance of losing player characters.¹⁰

The only thing lacking in this rule set– and I say this because I am positively dazzled by the possibilities of this system– is that it really needed an additional scenario book probably even more than it needed the campaign guide that it does have. It deserves to have a tight set of point build scenarios along the lines of what you see in Steve Jackson’s G.E.V. or in BattleTech or Star Fleet Battles. It deserves to have a set of linked scenarios that allow you to follow the exploits of a single commander over the course of several engagements while gradually introducing new rules and new units. (This style of campaign design is more often seen in computer gaming in titles such as Starcraft and The Battle For Wesnoth.) It deserves to have a stripped down set of campaign rules that allow for quick play without the need for spreadsheets to track all of the kingdoms and armies– and maybe with some sort of doubling cube type rule to eliminate all of the trivial battles from having to be played out. It deserves to have some sort of sandbox module that allows the players to form alliances and play out battles– sort of like Dwarfstar’s classic Barbarian Prince game but with more opportunity for large scale engagements.

This game is a wonderful resource, not only because opens up new possibilities for continuing role playing campaigns, but also because it brings to life and solves many of the problems surrounding the domain level play that is an integral part to the earliest role playing games. From a board gaming standpoint, it is not quite the complete package that something like Commands & Colors: Ancients is… but it nevertheless allows for a much tighter integration with the tropes and elements of role-playing games. While you might not fall into the target audience of this game’s niche, it nevertheless brings a great deal to the table for those that do. And it is far more likely to see actual play than a lot of other miniatures rules I’ve seen. This is a great game that deserves more attention.

—

¹ See James Maliszewski’s post Schrödinger’s Dungeon for more information on these dungeons which are an “adventuring site so large, open-ended, and dynamic that it becomes a campaign setting unto itself.”

² Joseph Bloch’s Megadungeon-Based Game Mechanics shows how design elements of AD&D are “much more pertinent to a large-scale dungeon environment, with multiple levels, [and] multiple possible objectives….”

³ The way that Michael Curtis’s Stonehell Dungeon leverages the one page dungeon concept while providing additional background information separately is quite remarkable.

⁴ James Maliszewki’s Dwimmermount megadungeon is now completed and available, brought to you by the same folks that published Domains at War.

⁵ Greg Gillespie’s Barrowmaze sees quite a bit of play and has garnered a great deal of praise.

⁶ Thieves are widely considered to be the most useless of the first level character types, but they are often the first to attain third level due to their extremely low experience requirements. Magic-users are similarly weak at the first level and have numerous constraints, but if they can survive to the higher levels they soon become the most powerful of all the classes. Modern design approaches tend to insist on complete balance between various class archetypes at all levels with uniform leveling thresholds. That’s how you do things for the fairness-obsessed “everybody gets a trophy” crowd.

⁷ You can get the counter sets using the POD option at RPGNow, but Tavis Allston tells me that they’ll be available in stores and on the Autarch website before long.

⁸ Note that this sort of morale system is an integral part of the Moldvay Basic combat rules and is essential to having the game being more than just about combat. Domains at War really seems to capture that sort of “diceyness” in the context of a larger battle. It may not be quite as elegant as the retreat flag dice results in Commands & Colors: Ancients, but the personalization of the attached commander’s moral modifier is well worth the hassle. Note that formed foot units get a bonus to shock rolls if they are adjacent to two friendly units, so keeping your lines intact is rewarded here as you would expect.

⁹ While Zak Smith’s Vornheim: The Complete City Kit may not be the original source of dice drop mechanics, it is surely among the chief popularizers of the concept. See page 38 for an ingenious method of using d4’s to generate floor plans. Also, instead of rolling on charts to generate a list of businesses on a city street, Zak has you dropping a handful of dice onto a page of boxes. Then there’s a method for determing to-hit, damage, and hit-location with a single d4 dice drop. Possibly the ultimate evolution of this idea is “Toss & Trace” method of mapping and stocking a location simultaneously. You can learn more about this last technique over at Telecanter’s Receding Rules.

¹⁰ Note that back in third edition Gamma World, this was one of James Ward’s recommended methods for helping low level characters survive their first few levels.

Note: For a description of the sort of miniatures battles that Gary Gygax was playing in the context of some of the earliest role playing sessions, please see Fight On! #2, which has an article by Victor Raymond that dissects a fascinating session report from an obscure issue of The Strategic Review from 1975.

I love how the Castalia House blog is catering to old-school nerd nostalgia. I remember the Boy’s Life serialization of The White Mountains, and now you’re name-checking practically every game I owned in high school!

-

You had really good taste in games!

-

Hey! It isn’t nostalgia if I’m reading them today!

There are no damage rolls in this game: each hit normally does a single point of damage.

That is very nice, although I’m surprised it takes half the hit points (If I’m reading that correctly, which I may not be) before flight becomes a serious risk. But as I think of it, can hit points be recovered? In other words, is the number of hits more correlated with fitness and exhaustion than casualties? Are casualties calculated as a factor of hit points lost?

Too often full hp refers to full and able-bodied ranks. I think this makes for more sensible attrition rates and a more fluid game. I must play.

-

Good question, because this really is the heart of the game.

Any unit damaged by magic and/or which is reduced to 1/2 hp or less by an attack must make a shock roll. This can result in anything ranging from standing firm to a total rout. While attached officers can add their morale modifier to the roll, being disordered, being at 50% hp, and being flanked accrue additional penalties. (And like I say about, formed foot get a bonus for being adjacent to two friendly units.)

Morale rolls occur when the general is destroyed or routed… or when the entire army is at 1/3rd units remaining. (Take out the general!) Morale checks mean every remaing unit rolls 2d6, with results ranging from rout to rally. If a unit rallies (result = 12+) then it actually gains a hit point back.

“Hit points” is a very rough term, to be sure… and as you can see units can rally sometimes, so it does not have a strict definition in this game. There are actually rules for pursing routed units with cavalry, so there’s more to this than what I’m saying, but for damaged units hold the field at the end… the percentage of hits taken is the casualty rate. Half of those are crippled/dead and half are wounded.

Thank you very much for the exceptionally kind and thorough review. I did not in my wildest dreams aspire to be compared to Steve Jackson.

I almost want to retire as a game designer now because I do not think I could get a better review than this for any future product ever.

Um…do you want to see the megadungeon I worked on?

-

I stand by the comparison.

When Steve Jackson created Melee and Wizard, rpg combat was mostly a rough, hand-wavy “theater of the mind” affair. He nailed that corner of the scene down with some extremely playable rules that are completely air tight. As far as I know, you’re the first to do something comparable on the mass combat side. (Not that people haven’t tried. I just don’t think it was possible to address this sort of thing well until after Richard Borg’s Commands & Colors series came along.)

But don’t quit designing, yet! There’s that scenario book I mentioned… and you might want to co-author a book with Kyrinn S. Eis to bring domain level play to 5th edition D&D.

-

Dragon Heresy borrows Alex’s domain rules alternate directly for domain level play using a modified SRD5.1 rules base.

I’m actively editing and formatting the final manuscript. I expect that the first half of 2018 will see a “basic rules” released *without* the domain game, because it’ll cater to levels 1-4 or 1-5, but if that does anything like “well” the full game will emerge this year. Mostly I just need the money to fill it with art.

-

Exciting to see the ACKS innovations begin to be more broadly used. Looking forward to DH!

-

The domain game is a core part of the setting at the mid and upper levels. One of the main reasons for sending folks into Tanalor, the basic trope-filled adventure and dungeon-filled stomping ground, is to collect revenue for the King of Torengar to prosecute a seemingly never-ending invastion by the “Neveri clansmen” (think mongol hordes) in the south, and officially opening up the ranks of the nobility to anyone that can pay the King’s Gift (the noble duty) accomplishes two things. It replenishes the treasury, and it also takes hordes of murder-hobos and gets them out of the realm.

-

-

-

I have owned Melee and Wizard since the 1980s in their original Metagame pocket boxes. I couldn’t agree more on how great those games are. I love them so much that I sometimes wish I’d built ACKS on The Fantasy Trip chassis. Having D@W compared to them is really a very kind compliment indeed.

Is someone working on 5th edition domain play? I don’t know Kyrinn S. Eis. 5th Edition is my favorite D&D edition in many years so it would be great to see it supported in that way, or help do so.