This novella was published last Friday, October 10, 2014. I had preordered it a few days before after reading the description at Amazon’s page.

That description is very misleading. And so is the title. This is not a story about “burned-out veterans, techs who’ve been warned off-planet, medics who weren’t much good on the ground” hauling cargo to the far reaches of explored space. And it is certainly not about a distant colony that “isn’t quite the end of the line, but it’s getting there.”

This book is a highly concentrated dose of loneliness in text form. Not just temporary solitude, but existential loneliness.

A crewmember wakes up from hibernation to find that some accident has caused the death of all her crewmates. She’ll have to spend the rest of the voyage awake and there is just not enough food. She knows she won’t make it but she doesn’t give up. We’re talking of an agony of several years until her supplies run out before she reaches Gliese-D. She knows what will happen. We are told what will happen. She tries anyway.

From time to time this main storyline is interrupted with flashbacks about her life back on Earth. And Valentine slowly reveals how sad and unappealing the protagonist’s life was back there. The only person that he thinks about is her own brother and those memories are blandly sad, not even bitter sad. It all adds to an anemic feeling of pointlessness.

She tries to stay alive but we rarely see her enjoying anything—not even memories or hopes. The only thing that gets her close to joy is listening to music. But that music doesn’t inspire her into any improvement, it is strictly an escapist experience. It often looks like Valentine is trying to draw a caricature of an atheist’s inner life seen through the eyes of a believer: tragic futility, never-ending darkness, and a cold merciless lack of Light… as if the story was begging to ascend towards the Franciscan dictum that all the darkness in the world cannot extinguish the light of a single candle. The protagonist keeps looking for the candle but the author won’t have it.

The only flicker of something resembling love from the protagonist is directed towards her unusual ship’s computer, the AI known as Capella.

Capella must be taking pity on me: it picks a chamber piece, where the notes are still a conversation, but there are only eight voices, and everyone moves forward together. Those stories are alike for everyone, and they realize everything that matters all at the same time. Everything’s settled.

“What is it?” I ask.

“Does it matter?”

Capella knows it doesn’t. I close my eyes.

Of course, that’s not love. It doesn’t matter. Nothing matters much, anyway. In space nobody can care about your defeatism and self-pity.

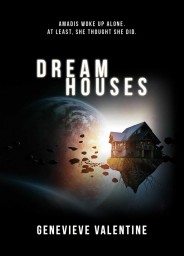

On the cover, however, there is a tagline that is not as misleading as the abovementioned description:

Amadis woke up alone. At least, she thought she did.

The question here is: At least, she thought she did wake up or at least she thought she was alone? Because again and again science fiction has to go back to asking just how lonely we are. And how terrible the answer might be. Then again, if life is tastelessly sad, what kind of company could be an improvement?

Hi Mr. Kratman