In Jon Del Arroz’s novella, Gravity of the Game, Commissioner Hideki Ichiro is growing frustrated as his attempts to bring baseball to the moon are frustrated by its low gravity. About to give up, he visits a sickly child in the hospital, whose love of the game rekindle Ichiro’s drive to succeed. But as he is about to pour the time and money needed to develop the technology needed to recreate baseball on the moon, an owners’ dispute threatens to remove Ichiro as commissioner of baseball. Can Ichiro hold onto his position long enough to bring baseball to the moon?

In Jon Del Arroz’s novella, Gravity of the Game, Commissioner Hideki Ichiro is growing frustrated as his attempts to bring baseball to the moon are frustrated by its low gravity. About to give up, he visits a sickly child in the hospital, whose love of the game rekindle Ichiro’s drive to succeed. But as he is about to pour the time and money needed to develop the technology needed to recreate baseball on the moon, an owners’ dispute threatens to remove Ichiro as commissioner of baseball. Can Ichiro hold onto his position long enough to bring baseball to the moon?

Del Arroz’s clever title carries more meaning than just the surface reading. Gravity certainly is the technical issue preventing baseball from being played on the moon. At the same time, Gravity of the Game is a love letter to the love of baseball, focusing not on the action on the diamond, but the impact that the game has on so many people worldwide. And it is this passion, from poor Make-a-Wish children in hospitals to fans at the field and at home, that Commisioner Ichiro has sworn to preserve–and makes baseball so attractive to its fans. Del Arroz brings to life the love of the game again and again throughout the novella, never letting it become cloying, saccharine, or nostalgic. Each character is genuine, and never played to stereotype, whether in culture or behavior.

This refusal to play to stereotype extends even to the plotting. It has become a refrain from authors published by Baen that if you have two separate problems, that there will be a solution that satisfies both. Usually this means throwing one problem at the other. And at first glance, the inventions that make baseball possible on the moon could certainly settle the longstanding owners’ territorial battle that threatens to end Ichiro’s tenure as baseball’s commissioner. Instead, Gravity of the Game chooses to illustrate the costs of clinging to the right action–and the potential rewards beyond.

This quiet dignity and grace fills the novella, and adds to its subtle appeal. Right now military science fiction and Hornblower-style naval adventures are the kings of science fiction, and even in other sub-genres, the crack of a rifle or the flash of a laser is never far behind. Gravity of the Game relies instead on the boardroom, where vision, greed, influence, and rule of conduct settle manners–and without the incipient threat of violence that accompanies such scenes in comics and in space operas. This allows Del Arroz’s characters to be older, and thus Gravity of the Game is a rare science fiction story with characters that live in the wide age gap between young adult and elderly mentor. Ichiro is already retired out of one career, as a baseball player, and he is old enough to have an empty nest. Few science fiction stories deal with the concerns of mature adulthood, whether middle-aged or beyond. Gravity of the Game is a cool sip of water for those bored of the eternal adolescence of science fiction.

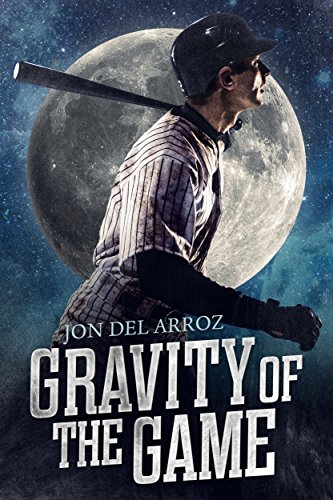

Finally, the artwork and design of the cover for Gravity of the Game is eye-catching, with a simple elegance no longer seen on the bookshelves. The cover for For Steam and Country has similar elements, creating a style unique to Del Arroz’s works. I hope that Superversive Press will continue to use this format in future works, as it is a distinctive signature that stands apart from the exploding spaceships and romance portraits that fill up the shelves and libraries.

In short, those looking for a science fiction story well outside the established banks of the genre should pick up Gravity of the Game.

Please give us your valuable comment