This is a guest post by Rich. Take it away:

It has now been more than forty years since small press stalwart David Madison shot himself dead in an Arlington railway yard. He was twenty six years old. I do not presume to understand why he did this. And I am not about to engage here in some De Campian style cod Freudian post-mortem analysis to try and explain it. He did what he did for reasons that seemed valid to him and we have no choice but to respect them.

It has now been more than forty years since small press stalwart David Madison shot himself dead in an Arlington railway yard. He was twenty six years old. I do not presume to understand why he did this. And I am not about to engage here in some De Campian style cod Freudian post-mortem analysis to try and explain it. He did what he did for reasons that seemed valid to him and we have no choice but to respect them.

Madison had a surplus of gifts as a fantasy writer, and we are all the poorer for being deprived of the work he might have produced. Such only makes it all the more of a shame that more effort has not been made into collecting together the work he did complete. Anyone who loves an imaginative and witty sword and sorcery yarn really owes it to themselves to track down Madison’s small press appearances. There really is nothing quite like his idiosyncratic Marcus & Diana stories.

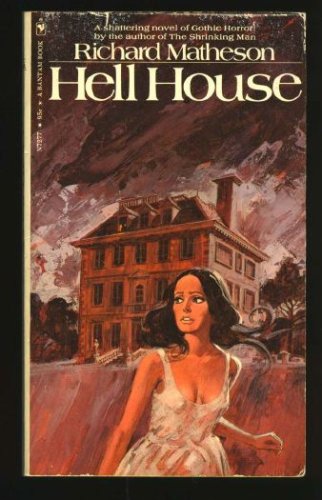

But for all Madison’s unquestioned talent as a fictioneer he was sometimes guilty of betraying his own emotional immaturity as a critic. Take the review of Richard Matheson’s HELL HOUSE which he published in July 1975 in an obscure and short lived fanzine called Kaballah, The Worlds of Fantasy.

Madison displayed no interest in appearing impartial, setting out in stark terms his intent to “flay” the book and “roll it in salt”. He then went on to call it the worst novel he has ever read before even beginning to address the novel’s supposed faults and failings. In a kangaroo court of this sort neither Matheson nor his work was ever likely to receive a fair hearing. Having stated his intention Madison proceeded to take issue with the book’s “concoction of trite dialogue, half-baked pseudo-science [and] illogical plotting”. He didn’t actually bother to back up these accusations with many examples of what he found so objectionable, trusting to his own Ellisonian sense of apoplexy and outrage to convince the reader.

But what appears to have really irked and irritated Madison most was the book’s treatment of its sexual themes. Madison berates the “sadistic sex scenes” and accused Matheson himself of being “a prude who treats lesbianism as an evil”. The hysterical tone of Madison’s umbrage on this point probably says far more about his own sexual hang ups than telling us anything useful about Matheson’s.

But if all this suggests that I am about to launch into a defence of the book and a rabid denunciation of my own of Madison’s arguments then the fact of the matter is that I’m not. Because if one takes the time to drain the emotional vitriol out of Madison’s criticisms then the stark truth is that he wasn’t altogether wrong about any of it.

For a book that continues to bask in its own classic status it can be disconcerting to discover just how sloppily written HELL HOUSE is. There are several instances of changes of scene which aren’t properly delineated, and at least one instance of a sequence segueing into a flashback without any kind of differentiation. Nor are these cute literary gimmicks either. But to what extent they are examples of poor copy-editing or Matheson’s own carelessness is open to question.

Boxes of scientific equipment miraculously appear without explanation also.

As Madison identified the book’s dialogue is flat and banal, which is surprising considering Matheson’s stature as a screenwriter. The plot is thin and largely uneventful for the first two thirds of the book. I personally lost count of the number of glasses of water that were run, the cups of coffee that were drunk and the amount of time characters spent settling down to sleep instead of doing anything more proactive. The shocks and scares are also quite humdrum [none more so than a levitated bed sheet saying “Boo!”]; at least until the possession of Florence Tanner late in the book belatedly injects a genuine frisson into them.

But although such criticisms are largely a question of individual taste Madison certainly was right to highlight the book’s strange sexual predilections. The problem isn’t that Matheson wrote a misogynistic book – which he had every bit as much right to do as the viragos penning rabidly misandristic fables do today – but that in doing so he contradicted his own central premise of Hell House being a hub of indiscriminate all inclusive torment and abuse. Because while the male characters of the book are subjected to physical violence none of it is sexually directed. But the female characters are on the receiving end of almost nothing but. The book takes an almost lascivious relish in having the prim and pious Florence Tanner expose her breasts not once or even twice but on no less than nine separate and distinct occasions. And Dr Barrett’s sexually conflicted wife Edith gets four opportunities to strip as well. In describing these scenes Matheson seems almost to adopt the voyeuristic persona of Emeric Belasco himself.

Now I daresay few people would have complained about seeing the lovely Gayle Hunnicutt and the beautiful Pamela Franklin disrobing to this extent in the film version, which Matheson himself scripted. But the film’s use of nudity is wholly innocuous and coy in comparison to the novel. A fact which forces one to query why Matheson believed explicitness so necessary in one medium and not in the other. Whatever the answer, the book’s abuse of its female characters cannot fail to cast in a strange light Matheson’s decision to dedicate the book to his daughters.

Madison and I part company at the juncture where he exhorts people to read HELL HOUSE for no other reason than to find confirmation of their own about how wretched the book is. Matheson was simply too accomplished a writer to produce something so shorn of all merit.

There is an interesting set of dynamics and tensions at work between the four principal characters which both compliment and counter-balance each other and in so doing cleverly mirror the book’s central conceit of the role of opposing physical polarities accounting for all psychical phenomena. And for a book which appears ostensibly to ridicule and refute orthodox religious doctrines there is a certain fitting symbolism in having four characters acting as evangelists for differing perspectives which, when fitted together, reveal a fundamental ‘truth’.

And it was unnecessarily churlish of Madison to deny the excellent head of steam which the book builds up towards the end when Matheson finally slips the shackles he’s been working with and unleashes a torrent of genuine horror.

But despite having these points in its favour HELL HOUSE is, in the end, a book which belies its reputation; much as the Belasco mansion itself does ultimately. For it is simply too preposterous to be taken seriously and has too little of the Grand Guignol about it to qualify as schlock.

The curious are better advised to watch the film instead which effectively boils the story down to less exploitative stock. And there one has the added pleasures of being able to see the late great Roddy McDowall at work in his prime and to gaze in awe at the ravishing Pamela Franklin.

“…trusting to his own Ellisonian sense of apoplexy and outrage to convince the reader.”

That’s a great little dig right there.