Regular readers of this blog are certainly familiar with the creeping sense of realization one frequently encounters when reading works written after 1940. Who among us hadn’t become all too familiar with the bait-and-switch tactic used to sell expressly anti-western civilizational works of fantasy and science fiction to an unsuspecting public? It is one of the hazards of being an open-minded and forgiving sort of reader.

Regular readers of this blog are certainly familiar with the creeping sense of realization one frequently encounters when reading works written after 1940. Who among us hadn’t become all too familiar with the bait-and-switch tactic used to sell expressly anti-western civilizational works of fantasy and science fiction to an unsuspecting public? It is one of the hazards of being an open-minded and forgiving sort of reader.

Recent years have provided the flip-side to that coin – the dawning realization that the unfolding story wasn’t written to subvert or mock your culture, but celebrate it. My first experience with that feeling came while reading John C. Wright’s Somewhither – the presentation of Ilya Murmomets’ father as a Catholic knight fighting to keep monsters out of our reality was standard fare, but the gradual reveal that his father was a genuine, white-hatted good guy whose views about the universe were right violated every convention established over fifty years of genre convention. Wright demonstrated to me that contemporary literature that was expressly Catholic in outlook could still be as powerful as Tolkein’s. Following quickly on Wright’s heels came Nick Cole’s Ctrl-Alt-Revolt! which reminded me that contemporary action novels could be completely serious at their core while taking the time to plant tongue firmly in cheek along the way, and Schuyler Hernstrom’s Images of the Goddess proved the opposite – that silly science-fantasy quests could reveal hidden truths about friendship and the instant bonds of brotherhood that arise from dangers faced shoulder to shoulder.

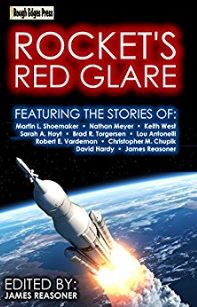

Now you can add Rocket’s Red Glare to the list. I brought a copy of this short story collection edited by James Reasoner sight unseen based solely on the inclusion of a story by Keith West. The rest of the stories were just bonus material. The first story out of the gate, Brad R. Torgersen’s Orphans of Aries¸ provided me with yet another experience of the best kind of slow dawn realization of a story bigger and better than expected, but any of the stories in this collection might have provided the same moment of clarity. Rocket’s Red Glare, as might be deduced by the title, is a collection of stories written from an explicitly pro-American point of view. And not the current trendy style of loving America because of it might be corrupted into something it is not or loving America only while it serves as a healthy host for foreign interests to take advantage of.

Orphans of Aries follows the adventure of an American ex-pat involuntarily trapped out among the stars when the galactic ruling council makes contact with Earth and chooses to treat with the UN rather than the interstellar pioneering American and British governments. In Torgersen’s tale, the Anglosphere tells the universe to get bent, we don’t need your permission to travel. If you won’t allow us access to your jump gates, we’ll just sod off and build our own, thank you very much. Fortunately for the ex-pat, Charlie Esterlan and for the Anglosphere as a whole, the galactic ruling council is as fractious as the UN. A coalition of alien races approaches Esterlan with an under-the-table offer; they have decided that helping the ostracized Americans break the galactic blockade suits their own purposes. Suspicious at first, and sensing a trap, Esterlan initially refuses. Fortunately for the reader, he reconsiders and proceeds to have the sort of adventure that one expects from a book with a cover featuring a rocket blasting away from Earth.

The universe in this first story presents a soft-edged stratification with the typical Precursor races at the top who are wise and powerful, but mostly aloof from the petty squabbles that provide the fun of adventure. At the bottom are those races who are newly come to the interstellar scene, of which Earth is only the latest. In between are the hordes of mature races who have been around long enough to establish themselves in the council and wield galactic standard technology without difficulty. It’s a tight little system that allows for drama and conflict while accounting for variable levels of technology and maturity among the alien races. But the best part about the setting is the underlying notion that the pugnacious Americans aren’t just right, but that for them, picking a fight against the universe isn’t a suicidal act – it’s a fight that they might win. Sure, it might take a while, but victory is possible.

That outlook is mirrored in Charlie’s experience. He used to be a pretty big fish in the pond of Earth, but at the story’s outset he works as a spaceport garbage man. While he might not be happy about the situation he plugs away at life, working diligently, and waiting for something to break his way. When an offer too good to be true drops into his lap, he searches his conscience and turns it down despite the opportunity to move beyond cleaning up the collective wastes of a hundred alien species. Down on his luck, he perseveres and refuses to compromise for the sake of expediency. That’s the sort of hero that a reader can respect and root for, and he makes for an excellent stand-in for the society he represents.

Kieth West’s follow up, Kieth West’s Manifest Destiny, follows suit with the hard science-fiction setting that is his stock in trade. In this two-part story, the UN has thrown off the shackles of the USA’s moderating voice by disbanding the Security Council, and thus the USA’s standing veto. This paves the way for the UN to arrogate to themselves the highest law of the land – the USA objects, and this sets the stage for a hundred and thirty year conflict in which the American forces attempt to isolate their off-world colonies from the cradle of humanity’s grasping one world government.

West begins the action with the American attempt to seal the colonies off from Earth, then picks up the action four generations later when the UN’s heirs finally break through to one colony in an attempt to bring the colonies to heel. The transition between these two chapters in the colonial dispute is seamless, with enough continuity and development to satisfy the reader that they are two parts of a whole, rather than two separate stories jammed together.

Where West’s tale differs from Torgersen’s is in the unspoken admission that the Earth-bound America eventually succumbed to the diktats of the UN. The shining city on the hill may have gone out, but not before its citizen’s took the light of liberty out to the stars where it could be nurtured safely away from the grasping hands of those who are unable to see the clear links between liberty and prosperity.

Based on the strength of the first two stories in this collection, chalk Rocket’s Red Glare up as a win for the good guys. It’s the sort of superversive storytelling that features good men succeeding through a combination of determination, honor, and good old fashioned American ingenuity. That style of storytelling was once ubiquitous but has since been subverted and deconstructed so often that reading tales unabashed respect for the US of A is as refreshing as it is surprising.

Thanks for the review, Jon! Sounds like Poul Anderson would’ve loved this antho, and that’s about the highest praise I can think of.

Jim Reasoner is a great guy. A fine editor, an author who loves the pulps and writes at pulp speed and something of a Robert E. Howard scholar. Meanwhile, he keeps his blog updated regularly. An example to us all.

His blog:

http://jamesreasoner.blogspot.com/

Rough Edges Press:

Jon,

Glad you liked the first two stories. I’m still reading the anthology, but the ones I’ve read so far have the same attitude, although not all are set in space.