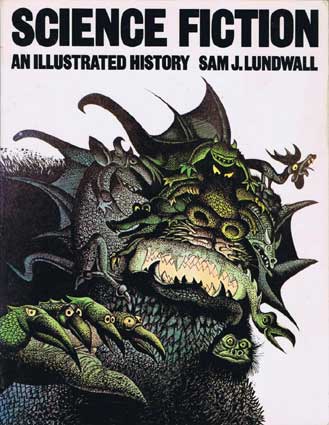

Author JD Cowan examines Science Fiction: An Illustrated History, by Sam J. Lundwall in the first of many parts. Written in 1975, during the tumultuous years just after John Campbell’s death, Lundwall’s account offers an examination of science fiction history unclouded by the revisionism that accompanied the latest editorial handover in the mid-2000s. Lundwall, a Swedish member of SFWA and other SF organizations, set out to “prove that science fiction is a worldwide phenomenon that hadn’t blossomed in English speaking countries until post-World War I.”

Written in 1975, during the tumultuous years just after John Campbell’s death, Lundwall’s account offers an examination of science fiction history unclouded by the revisionism that accompanied the latest editorial handover in the mid-2000s. Lundwall, a Swedish member of SFWA and other SF organizations, set out to “prove that science fiction is a worldwide phenomenon that hadn’t blossomed in English speaking countries until post-World War I.”

While a European perspective is welcome, as it counteracts American science fiction’s continued provincial myopia concerning World science fiction, Lundwall does a disservice to Poe, Wells, and Burroughs in his claim. Furthermore, English language science fiction was thrust in the limelight after World War I because France, Germany, and other nations involved in both science fiction and World War I lost the spark of hope for the future needed to write science fiction and abandoned the field. American and English science fictions were the loudest voices in a much-diminished choir.

Lundwall and Cowan’s conversation on science fiction sparks many points of discussion, such as the earliest works in the form, how science fiction’s secularization killed its spirit of wonder, and more. Lundwall offers science fiction as the mythology of progress, while Cowan is quick to point out where the mythology diminishes itself:

Mr. Lundwell continues to pry a genre definition from half-formed ideas and made-up terms in order to put to paper what science fiction is. The fact is that it doesn’t have one, and that might be because it is not much in the way of a standalone genre.

Unlike, say, mystery which is about mystery, or romance which is about romance, or adventure which is about adventure, if your genre requires mental gymnastics to explain to a child then you should go back to the drawing board. One sentence should be enough. Genres aren’t aesthetics or themes. Genres are defined by what emotion and sense they are meant to invoke in the reader. This is why the average reader picks up a book. They choose one based on the experience it will give them.

What they are fumbling around to define in the above definitions is Wonder. Wonder is a trait from adventure fiction and its subgenres fantasy and horror. It is the adventure of exploring new lands, peoples, and possibilities. Pair that with the origins of those listed in the paragraph above and you will see where I am going with this, and why the battle for an original definition has been fruitless for well over a century. It’s never going to have one, and that is a point that should be discussed more than it is.

That science fiction might be closer to chinoiserie than mystery or horror is a point to ponder. But it is the following exchange which highlight Lundwall’s claim of science fiction as a global phenomenon–and gores a sacred cow of science fiction in the 2010s:

And to quash another canard, the author continues:

“When some critics argue that the English author Mary Shelley invented modern science fiction with the novel Frankenstein (1818), they forget that she was drawing upon more than fifty years of Marchen literature, most of it infinitely better and more modern than Frankenstein was.”

No, that wasn’t written by Jeffro Johnson. In fact you will soon see that the author is no friend of the pulps or the old stories at all. There is a larger point here. This is a man who stood at fandom’s heart, and here he is admitting what no one currently in that position will. If you accept Mary Shelley as science fiction (and horror, when it’s convenient to the argument) you have to accept many other works that came before hers. You do not get to pick and choose.

You have to accept fantasy and horror as a whole connect to science fiction, and she did not create either of those. She merely continued on in a tradition that started long before she was born and continued long after she was dead. Despite fandom’s best efforts to rewrite the past, she did not create the genre. She was a participant in a unending conversation called art and had her piece. This should be enough.

Those using Shelley as a bludgeon for political reasons are doing her work and those who came before a disservice and are actively whitewashing history–a history, I might add that was crystal clear from all the way back in 1977. Even fandom understood this.

Let’s turn again to Lundwall for an explanation of Marchen literature:

“Modern science fiction in a sense appeared with the German romanticists of the late eighteenth century–Clemens Brentano, Achim von Armin, Adalbert von Chamisso, E. T. A. Hoffman and others. These romantic Marchen writers wrote what in effect were fairy tales for adults, including all the various paraphernalia common in modern sf, such as robots, monsters, strange machines etc, set against a curious background. They demanded an almost boundless credulity from their readers, for they described life, not as a reality, but as a dream of sorts–not what it is, but as it might be.”

We see once again the influence of Romantic literature, with this branch in fairy tales, joining English Gothic tales and Poe’s mysteries as the venerable roots of science fiction. Cowan and Lundwall will disagree yet again over the merits of the Gothic tale, this time, over the appeal of materialism:

But here is where we get the writer’s real opinion of adventure fiction. What follows is his description of The Castle of Otranto, the single most important and popular Gothic novel.

“It had form and no substance, it horrors all lay on the surface as it were . . . the seminal The Castle of Otranto succeeded only in building up baroque facades without much content. In many ways this was the forerunner to the Penny Dreadfuls and the pulp magazines–lots of form, no content.”

I will translate this from arrogant fandomese for the paupers in the audience. “Form and no substance” means the horrors are spiritual, implied, and obvious to those reading, and not explicit.

Cowan describes further the importance of the Gothic:

The Gothic is the beating bloody heart in any good traditional romance story and is what gives it the universal core so needed in fiction. White against black. Dark against Light. Hero against Villain. Eternal Life against Endless Death. Temptation against Virtue. It goes beyond the surface into weighty themes of the Ultimate, God, and True Justice. The knowledge of a battle between forces beyond both parties at play that haunt the scenery and the overall world behind the story. It underpins every action and decision, and the thought that salvation or damnation is a stone throw away is the most nail-biting experience of them all. Now those are stakes, and they were an integral part of all fiction until the second half of the 20th century where the worst thing that can happen to you is that a monster might kill you in the dark where you can’t see it.

Really makes you think.

Indeed, it does, with this discussion of the first chapters leaving readers much to ponder over. I look forward to the rest of this series, and the continued conversation between 1970s’ science fiction orthodoxy and 2010s’ independent rebels.

Please give us your valuable comment