Seabury Quinn, A Lesser Light that Still Shines for Those Who Care To Look

Wednesday , 12, September 2018 Pulp Revolution 9 Comments Flipping through the bright and evocative covers of old pulp magazines such as Weird Tales, the name Seabury Quinn pops up with a regularity at odds with his current place in the annals of fantasy and science fiction. His stories of occult mystery served as excellent source material to inspire the sort of titillating eye grabbers that helped to make the pulp magazines of the day so popular. Unlike many of his better-known pulp contemporaries, Quinn earned his living as a lawyer specializing in mortuary jurisprudence, a handicap that didn’t prevent him from publishing four or five stories every year during a career that spanned more than four decades. Depending on how one counts, the man published sixty-seven short stories, thirty-four essays – many published in the letters section of Weird Tales – and forty-six tales of Jules de Grandin. (Infogalactic and the Intenet Science Fiction Database disagree on the final count.) Where most of the pulp author hall of fame writers achieved that distinction by way of an all too brief career filled with home runs, Seabury Quinn earns his place as a consistently entertaining writer whose works never fail to entertain, even if they never quite rise to the level of fun of a Lovecraft or Howard or Moore.

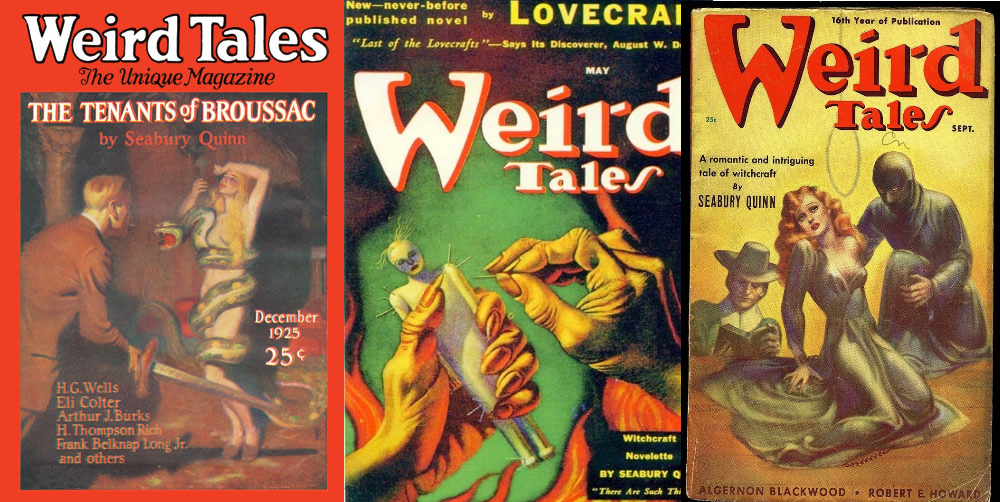

Flipping through the bright and evocative covers of old pulp magazines such as Weird Tales, the name Seabury Quinn pops up with a regularity at odds with his current place in the annals of fantasy and science fiction. His stories of occult mystery served as excellent source material to inspire the sort of titillating eye grabbers that helped to make the pulp magazines of the day so popular. Unlike many of his better-known pulp contemporaries, Quinn earned his living as a lawyer specializing in mortuary jurisprudence, a handicap that didn’t prevent him from publishing four or five stories every year during a career that spanned more than four decades. Depending on how one counts, the man published sixty-seven short stories, thirty-four essays – many published in the letters section of Weird Tales – and forty-six tales of Jules de Grandin. (Infogalactic and the Intenet Science Fiction Database disagree on the final count.) Where most of the pulp author hall of fame writers achieved that distinction by way of an all too brief career filled with home runs, Seabury Quinn earns his place as a consistently entertaining writer whose works never fail to entertain, even if they never quite rise to the level of fun of a Lovecraft or Howard or Moore.

Just a few of the many covers that use his name to move copies

I suspect that his stories don’t have as much cultural traction among genre fans because unlike authors such as Howard or Lovecraft, they don’t provide the natural fodder for tabletop gaming that played such a heavy role in keeping the works of those authors alive. They fit into one of those little nooks and crannies between fantasy and hardboiled detective that results in stories that don’t quite appeal to either fanbase these days.

His most popular series, the Jules de Grandin mysteries, feature a diminutive French doctor and occult dabbler drawn into mysteries that traipse along the border of reality and the supernatural – a more robust and blonde, blue eyed version of Hercule Poirot. The narrator of his adventures, and Watson to de Grandin’s Sherlock, is friend Trowbridge, a doctor of a more mundane persuasion who serves as an audience insert character to whom de Grandin can explain the clues that lead him inexorably to the solution to the puzzle of the story. “I am never mistake,” he boasts and not without cause.

Facing down werewolves, Satanists, ghosts, Hindu demons, and every other sort of night creeping boogeyman, de Grandin mysteries typically feature a strange set-up, an illness to treat, a haunted house to exorcise, or a medical coroner’s error to rectify. Between the set-up and resolution, the reader can expect frequent interrogations with witnesses cooperative and otherwise, creeping moments of dread in hot pursuit of a mortal threat, and a little gunplay on the part of the veterans de Grandin and Trowbridge. Where de Grandin separates himself from his clear inspiration, the aforementioned Sherlock Holmes, is his friendly and open attitude and unabashed romantic side. Many of his mysteries revolve around an unrequited love that either causes the problem or inspires him to greater efforts to resolve it so that love can flourish in the wake of his solutions. Unlike other series, particularly the mysteries popular in titles such as “Dime Mysteries”, one never knows whether de Grandin faces actual forces of the occult or if the mystery unravels to provide a mundane solution that owes more to science and reason than religion and witchery.

The de Grandin stories also generally feature happy endings, for most of the participants at any rate. The required minimum body count of one, to raise the stakes of the drama, means that innocent bystanders or red-shirted allies of the doctor find themselves pressed into service of a mortal nature. Despite the setbacks, good triumphs, love wins, and the forces of western civilization prove to be more powerful than their rivals. Though not always, as in Gods of East and West, the doctor finds himself calling on the services of Celtic mythology and the Lakota faith to help defeat a Hindu demon that simple Christian faith alone could not withstand.

The de Grandin stories also generally feature happy endings, for most of the participants at any rate. The required minimum body count of one, to raise the stakes of the drama, means that innocent bystanders or red-shirted allies of the doctor find themselves pressed into service of a mortal nature. Despite the setbacks, good triumphs, love wins, and the forces of western civilization prove to be more powerful than their rivals. Though not always, as in Gods of East and West, the doctor finds himself calling on the services of Celtic mythology and the Lakota faith to help defeat a Hindu demon that simple Christian faith alone could not withstand.

Which leads us to the blue-haired elephant in the room, and that’s the contemporary mores of the stories Quinn provides. A man of his time, his characters exhibit the usual sort patriotism and omni-nationalism that has fallen out of favor among the literati of our day. Which is not to say that the tales are racist or nationalist so much as that the characters, as well-rounded examples of the day, hold such views. And unlike the current assumption of two major factions, Europeans against a rainbow coalition of the rest of the world, the slight asides are as likely to be between members of those tribes as against anyone else. Americans sling stones at French, French dint Spaniards, and everyone sneers at the Irish. Except for de Grandin, whose open-mindedness to matters of occult carries over into open-mindedness in matters of culture. He’s a “best tool for the job” sort, and a bit of an Indiana Jones precursor in his professed preference for stolen or liberated treasures from around the world to be returned to their rightful owners or placed in a museum for proper care and study. A five-volume collection of the de Grandin mysteries can be found on Amazon, though only two appear to be available in digital format today.

Seabury Quinn’s last published work, Alien Flesh, was published eight years after his death, suggesting some last lingering interest in his works. The story of a male Egyptologist magically transformed into a woman, Infogalactic describes this novel as a sexually explicit erotic fantasy. So maybe Quinn’s place on the shelf more properly belongs nearer the New Age perverts than the pulp miners after all. As a well-adjusted and decent man, I’ll give the novel a pass, but the numerous short works I’ve read of Seabury Quinn provide solid and entertaining reads that won’t keep a man up at night worried about tings that go bump in the night, nor will they keep him relentlessly turning pages to find out what happens next.

What they will provide is a fun glimpse into the foreign country this is our past, and a better appreciation for the “out there but not too out there” stories that provided an important stepping stone from the myths of the 19th century to the serious cultural business of sci-fi that marked the latter half of the 20th century. If the 21st century’s writers can dilute the seriousness of the latter with the wonder and cultural pride of the former, we’d all be a lot more satisfied with life in the west.

Thanks for putting a spotlight on an author who should be better known. Is he as good as Howard or Lovecraft? Nope, but he’s still better than 90% of what is written today. He’s good enough and he’s consistent; I know that some people don’t like the De Grandin stories, but they’re entertaining enough if you don’t binge on them.

* That 5 volume collection isn’t complete yet; volume 4 comes out this month and vol 5 is due in the spring of ’19.

* I found the De Grandin stories to provide a wealth of material for low level scenarios (my players were weenies) for my Call of Cthulhu campaign. Took a little bit of work, but was doable.

Received the hard-bound Volume Four in the mail within the past hour. And just before reading Jon’s post.

The four current volumes are very handsome sitting side-by-side on the shelf. Thank you to Jon for his article, and to Night Shade Books!

And all are now available on the Kindle. Even #5, when it is released in March 2019.

Seabury Quinn was the original WT’s most prolific contributor. I also suspect he may have been more popular with many of the magazine’s readers/buyers of the time than Lovecraft, Smith or Howard. Clearly his work was welcomed by the editors and, as you note, provided inspiration for some good covers. One-time pulp editor R. A. W. Lowndes reprinted many of the De Grandin stories as lead items in his late 1960s revival digest Startling Mystery Stories, and again they proved very popular with the readers.

Quinn also wrote “Roads”, the best Weird Christmas Tale I’ve ever read, featuring Santa Claus as a gladiator made immortal by a grateful Christ Child.

Quinn was indeed the most popular Weird Tales author during it’s original run. But I have to say, he was without a doubt the definition of a hack writer.

I read the first volume of his collected Jules De Grandin stories, and I can certainly see why he is not well remembered today. He recycles plots over and over, Dr. Trowbridge is constantly shocked at supernatural occurrences even though roughly the same thing occurred last week, his twists are never clever, etc.

This is the kind of muck that gives pulp fiction a bad name.

Roads was okay, though.

Quinn was indeed the most prolific author within Weird Tales. Jules de Grandin took up a 100 issues, 2 of which were reprints.

He moved also to Short Stories Magazine, Jungle Stories, Thrilling Mysteries and over 125 stories were not about the accursed little French Man!

As you said his main work was writing articles about Mortuary Juirisprudence, first for Sunnyside and Casket, then, having fallen out with the owners of S&C, for the Dodge Chemical Company and their in house magazine.

He was not above recycling plots and ideas, but who wasn’t at the time? His last story appeared in 1964, Master Nicholas, which echoes Daniel Webster and the Devil.. A fun story, as many of them were.

His Pofessor Forrester series, which are crime stories with hints of bizarre happenings are really original.

Chris Worthington

[…] Seabury Quinn: the Lesser Light that Still Shines […]

Beware all men who claim they are “well-adjusted” and “decent”.

It’s just a rule I have.

😐