Sensor Sweep: Moon Pool, Talismans, Sea Wolf, Jerry Pournelle, New Heinlein

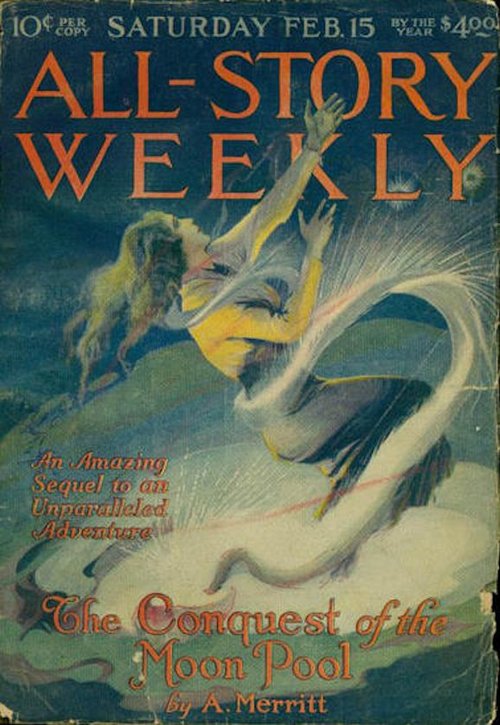

Monday , 18, February 2019 Sensor Sweep 6 CommentsFiction (DMR Books): One hundred years ago today, A. Merritt‘s novella/short novel, “The Conquest of the Moon Pool,” was unleashed upon an eager  public. The story which spawned it, “The Moon Pool,” had been met with such an outpouring of enthusiasm by the readership of All-Story Weekly that the pulp’s legendary editor, Robert H. Davis, practically demanded that A. Merritt write a sequel. Seven months later, Merritt delivered the goods.

public. The story which spawned it, “The Moon Pool,” had been met with such an outpouring of enthusiasm by the readership of All-Story Weekly that the pulp’s legendary editor, Robert H. Davis, practically demanded that A. Merritt write a sequel. Seven months later, Merritt delivered the goods.

Fiction (DMR Books): Welcome to Part Two of my re-read of A. Merritt’s classic and influential novella, “The Moon Pool.” In Part One, I posted a brief excerpt from the “Introductory Letter” which prefaced the original publication of “The Moon Pool” in All-Story Weekly. The letter is supposedly from the president of the International Association of Science, explaining why the story was appearing in an American pulp magazine and also thanking A. Merritt–who actually held a fairly prestigious position in the newspaper industry at the time–for arranging the facts into a publishable narrative.

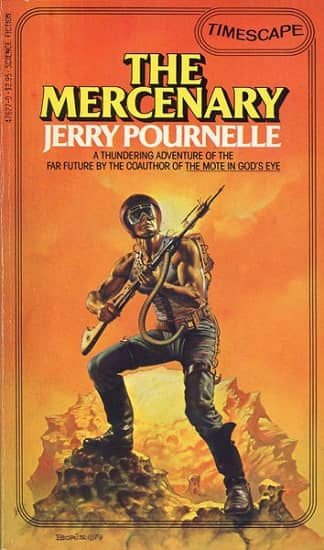

Fiction (Black Gate): The very first Campbell Award, in 1973, went to Jerry Pournelle. Writers are eligible for the award for the two years after their first  professional SF/Fantasy publication. While Pournelle had published a thriller, Red Heroin, in 1969 under the name Wade Curtis, his first SF story was “Peace With Honor,” under his own name, in the May 1971 Analog. This was the first story in his Co-Dominion future history, and the first to feature John Christian Falkenberg, one of his primary heroes. His nomination was based on that story, on another Falkenberg story, “The Mercenary,” and on the novel A Spaceship for the King (set much later in the Co-Dominion universe), as well, perhaps, on three stories that appeared in Analog under the “Wade Curtis” name: “Ecology Now!”, “A Matter of Sovereignty,” and “Power to the People.”

professional SF/Fantasy publication. While Pournelle had published a thriller, Red Heroin, in 1969 under the name Wade Curtis, his first SF story was “Peace With Honor,” under his own name, in the May 1971 Analog. This was the first story in his Co-Dominion future history, and the first to feature John Christian Falkenberg, one of his primary heroes. His nomination was based on that story, on another Falkenberg story, “The Mercenary,” and on the novel A Spaceship for the King (set much later in the Co-Dominion universe), as well, perhaps, on three stories that appeared in Analog under the “Wade Curtis” name: “Ecology Now!”, “A Matter of Sovereignty,” and “Power to the People.”

Cinema (Future War Stories): On December 14, 1984 one of the most ambitious science fiction films was released: DUNE. This unique science fiction film saw the merging of the young talented director in David Lynch, the experienced hand of the De Laurentiis family, the music of Toto and Brian Eno, a wealth of talent behind the camera that designed the universe of 10,191 AG. All of this was built on the foundation of the legendary 1965 novel of the same name by Frank Herbert that has been praised as the best science fiction book of all time. To breathe life into the pages of the book was one of the best casts were assembled for a sci-fi film ever.

Cinema (Kairos): Last night I made a special appearance on Geek Gab to discuss my new mecha mil-SF book Combat Frame XSeed and its impending sequel. During the show, I was asked if I’d seen Star Wars Galaxy of Adventures. I hadn’t, because I know that Star Wars’ current owners secretly hate me. Doing some cursory research, I discovered that their hatred is no longer secret.

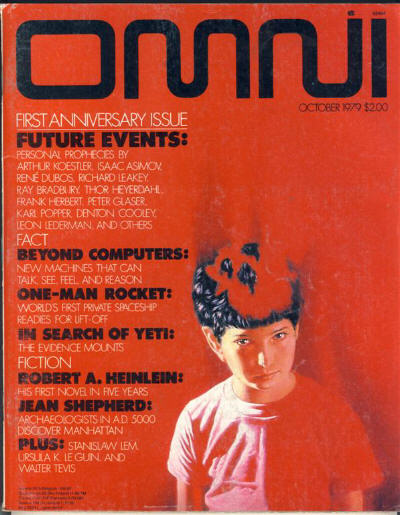

Fiction (Pulpflakes): Phoenix Pick recently announced that, working with the Heinlein Prize Trust, they have been able to reconstruct the complete text of  an unpublished novel written by Robert A. Heinlein.

an unpublished novel written by Robert A. Heinlein.

Heinlein wrote this as an alternate text for THE NUMBER OF THE BEAST. This text of approximately 185,000 words largely mirrors the first third of the published text, but then deviates completely with an entirely different story-line and ending.

Science Fiction Fandom (Between Wast & Sky): Last time we talked about the beginnings of genre fiction and how everything you read emerged from the same place and only split apart due to preferences of those who seized control of the industry in order to mold it in their image. Before the 20th century all stories gelled in very straightforward genres. That is, until self-proclaimed experts decided to redefine words and meanings to fragment out what they didn’t like from their chosen genre and lock them all to isolated islands. Things had changed hard in mere decades.

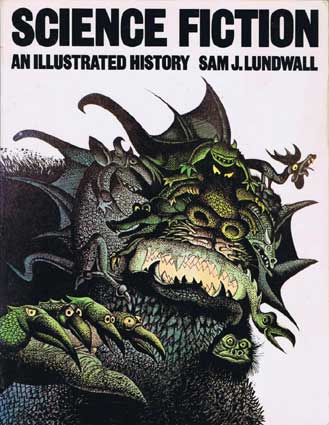

Science Fiction Fandom (Pulp Archivist): Curious in reading Lundwall and Lewis, it is the post-Campbellian magazines of Fantasy & Science  Fiction and Galaxy that appealed to European critics more than the drab technical work of Gernsback and Campbell.

Fiction and Galaxy that appealed to European critics more than the drab technical work of Gernsback and Campbell.

I have previously noted that the Campbelline Revolution never thrives where and when Campbell is not present, and that attempts to graft cuttings from the Campbelline tree onto French and Japanese science fiction inevitably wilted.

Fiction (HiLoBrow): In this grown-up version of Kipling’s Captains Courageous, an effete young intellectual — Humphrey van Weyden, whose favorite philosophers are Nietzsche and Schopenhauer — is rescued from a shipwreck in the San Francisco Bay by a brutal schooner captain, Wolf Larsen, who takes his unwilling passenger along on a seal-hunting voyage. Larsen is a quasi-Nietzschean cynic who believes in nothing but the pursuit of pleasure and the triumph of strength over weakness; he thoroughly enjoys browbeating “Hump” while forcing him to do menial work and learn how to defend himself.

Cryptozoology (A Strange Manuscript): In February 1899, a cargo ship brought to Sydney, Australia, the skeletal remains of a huge “two-headed sea serpent” – said originally to weigh seventy tons and extend sixty feet in length – that was found on a beach on Rakahanga island in the Solomons. The find was significant enough to reach the newspapers in the United States. On April 5 of that year, the Los Angeles Herald described the discovery as follows:

Comic Books (Gaming While Conservative): Every time another issue of “Chuck Dixon’s Avalon” hits my inbox, my heart skips a beat.

Don’t get me wrong, I like “Alt-Hero: The Series Not Written By The Legend Chuck Dixon”, well enough. Each issue’s strategy of introducing hordes of named characters that you’d like to see more of but never do because the next issue also has to add six more names to my already overtaxed memory is an exciting and bold new approach to story-telling.

Fiction (Black Gate): The 1930s Golden Age of Weird Tales was in full force with the three main first stringers present: Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton  Smith, and C. L. Moore. Carl Jacobi, while not a headliner author, always produced good-to-excellent horror stories. The Arthur J. Burks story is a reprint from 1927. Burks was the sort of middling writer along the lines of Otis Adelbert Kline and Seabury Quinn that editor Farnsworth Wright was comfortable publishing. The only real weak story was by Dale Clark. Farnsworth Wright has a penchant for barely competent and unmemorable stories of this sort.

Smith, and C. L. Moore. Carl Jacobi, while not a headliner author, always produced good-to-excellent horror stories. The Arthur J. Burks story is a reprint from 1927. Burks was the sort of middling writer along the lines of Otis Adelbert Kline and Seabury Quinn that editor Farnsworth Wright was comfortable publishing. The only real weak story was by Dale Clark. Farnsworth Wright has a penchant for barely competent and unmemorable stories of this sort.

RPG (RPG Pundit): One way to tell a faker from someone (potentially) genuine is to look at the magical accouterments they use. Are they going around with a fancy-looking crystal-encrusted rune-marked perfectly-straight wand that may have been store-bought or ordered from Etsy? They’re 99% likely to be frauds.

One of the best “sweeps” I have read. Gave me two new blogs to read as well as revisiting two others.

Thanks for linking!

Thank you for the link!

Regarding the “NEW” Heinlein:

I wonder if this is the first version of NUMBER that RAH wrote (after his extended illness) that Ginny nixed, saying it wasn’t up to snuff. That version is accessible (or at least was back in 2014) at the Heinlein Archives for a small fee to download. What you got was an uncorrected, typewritten pdf.

-

Did you read the linked blog post?

-

From that linked blog post-

“There has been speculation over the years about a possible alternate text, and the reason it was written, particularly since one book is not just a redo of the other ─ these are two completely different books.”

From the Heinlein biography published in 2014:

“Heinlein was able to write “The End” on the new novel before the trip to Atlanta. He finished it early one morning and left the completed manuscript on the kitchen counter for Ginny to read, as usual, and went to bed.

“Ginny read through The Panki-Barsoom Number of the Beast with growing puzzlement. The story was straightforward enough—two newlywed couples fleeing across alternate realities from alien villains he called “Black Hats” (the Barsoomian name for these “vermin” was Pankera, pl. Panki). She put down the manuscript. While it was perfectly competent yard goods, it just wasn’t a Heinlein novel.

“She knew what she had to do—and she could not bring herself to do it.

“Over the years, Heinlein had always sat down at the typewriter wondering if he could pull it off one more time, and maybe he had just reached the point where he couldn’t. This could be the end of his writing career. It would be devastating for him. It was “not best work,” she told him.60 “I took that responsibility very seriously,” Ginny later said. “The idea that I just had to tell him not to try to publish it was—almost a death-knell for us.

“This was the first time Heinlein had to confront his faculties failing in some important way—and it meant more for him than simple old age. The possibility he would go like his father or his mother—mind gone for years, or flickering in and out—was disturbing. “We just thought it would be that way,” Ginny said simply.”

Patterson Jr., William H.. Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue with His Century: 1948-1988 The Man Who Learned Better: 2 (p. 394). Tom Doherty Associates. Kindle Edition.

I downloaded the manuscript from the Heinlein Archives six years ago.

http://www.heinleinarchives.net/upload/index.php?_a=viewProd&productId=441

-