It does bother me.

It does bother me.

Going back and reading the old books, getting excited about them, wanting to explain what it is I’m seeing, I’ll necessarily come back with an imperfect abstraction. One brief enough that people will actually read what I have to say. And so many people have never even heard of these books and these authors. Or if they have, they’ve heard nothing but bad. So some of them go read for themselves and then they come back sputtering, mostly just due to the pure joy of it all. But also for the pure strangeness of the fact that no one ever told them that this was there.

That happens. But just as often, there are the people that don’t want to believe it. They are content with contemporary science fiction and fantasy more or less as it is. Or maybe they are reformers that only want to make modest, incremental changes. Or maybe they see the cachet that the old works have and want to position themselves as having the same spark and energy. Or maybe they see that people really like the old books and it just hurts that the things that they like aren’t as cool. And they want the things that they like to be cool, too… so without reading they look at the Appendix N discussions, extract out talking points and some sort of checklist… and then they say, “see…? There’s no difference!”

Ah, there is a difference. But how to explain it to someone that can’t or won’t see it…? The world is certainly a different place if your reference points are primarily movies and television. They’re another thing altogether if the short stories, novellas, and standalone short novels of the science fiction and fantasy canon comprise your definition of normal. And the former is the case even for people that really like to read these days.

But something clearly got lost in the translation in the creation of the film adaption of Dune by David Lynch. (It would not be a surprise if it came out that the man didn’t even bother to read the book.) The Peter Jackson adaptions of Tolkien’s work are worse. So much is carried forward from the books and implemented in exacting detail by countless artists. And yet side by side that effort at remaining true to the source material, there is the egregious addenda and revisions necessary to interpolate the story into a cultural context that is both foreign and antagonistic to the source.

The results are necessarily incoherent. And maddening. And anyone that attempts to appropriate a pulp ethos by following a checklist will necessarily fall prey to the same error. It is a matter of culture.

Again, you can take an aspiring artist at random. A twenty year old, maybe. Tell her to be crazy creative. Do something different. Wild. Provocative. Make a statement, something no one else would do. Turn her loose, give her carte blanche to be really off the wall… and it’s amazing. The actual range of what you get is going to very, very narrow. Anyone that’s read a college literary magazine or been to a senior art thesis knows what I’m talking about.

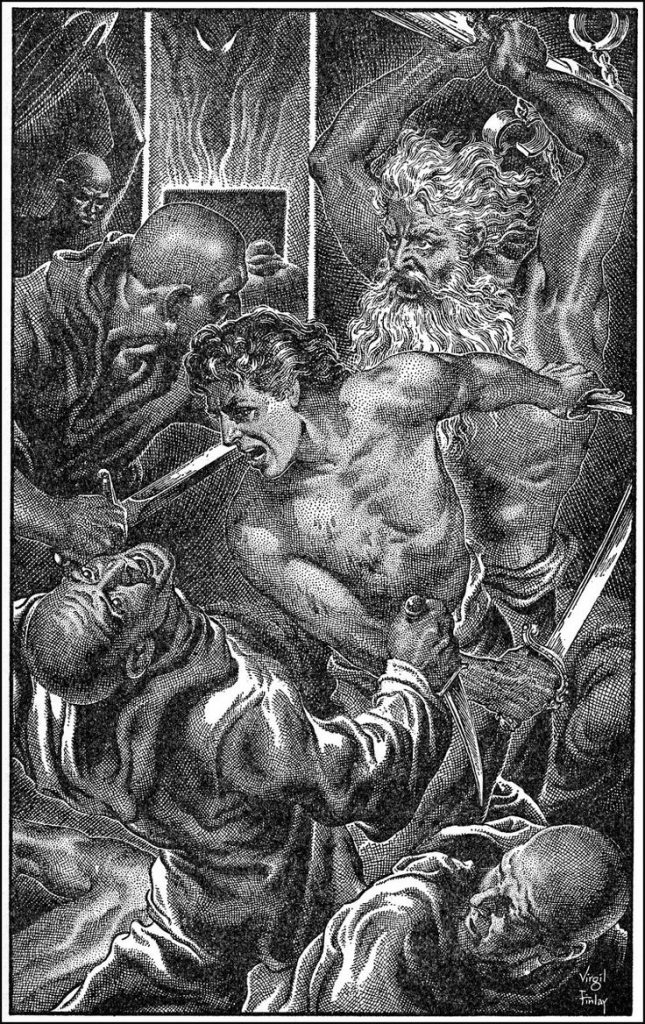

People today won’t just spontaneously write like A. Merritt, of course. Artists don’t get a yen to come up with things like the Virgil Finlay illustrations of his work either. And that impulse that drives people to do something “new” or “clever” or different is almost always in lockstep with culture. And the old books are expression of an entirely different culture.

There is an unfathomably distant gap involved in this.

What then if someone from today wanted to write something “pulpy”? Most of the time you’ll get a caricature. Or a few things that are cherry picked from older works that are (again) held together by cultural touchstones that are entirely at odds with the way things used to be done. It’s like the difference between a dimensional shambler… and a crazy man wearing the hide of a dimensional shambler. It’s a completely different thing.

So no, you can’t really reconstruct the old pulp idiom from the generalizations I’ve made about them. Checking all the boxes of things I’ve praised in them… you know, that stuff was not even the tip of the iceberg.

I can point out that A. Merritt does absolutely astonishingly things with language that no one would do:

Up from the depths of the turquoise sea thrust thousands of rocks. Rocks blue and yellow, rocks striped crimson and vivid malachite; rocks all glowing ochre and rocks steeped in the scarlet of autumn sunsets; a polychrome Venice of a lost people of stone, sculptured by stone Titans. Here a slender minaret arose two hundred feet in air yet hardly more than ten in thickness; here a pyramid as great as Cheops’, its four sides as accurately faced–by thousands, far as eye could reach, the rocks arose in fantasies of multi-colored cone and peak, aiguille and minaret and obelisk, campanile and tower.

I can point out how he does absolutely astonishing things with his characters that no one would do today:

As though he had called to her, she opened sleepy eyes–sleepy eyes that as she looked at him grew sweetly languorous.

“My own dear lord!” whispered Sharane.

She sat up, motioned the girls to go. And when they had gone she held out white arms to him. His own arms were around her. Like a homing bird she nestled in them; raised red lips to his.

“Dear lord of me!” whispered Sharane.

I can point out how he does absolutely astonishing things with passages that read like description of Jack Kirby artwork:

Kenton looked out upon depth upon depth, infinity upon infinity of space. Myriads of suns were hived therein and around them spun myriad; upon myriads of worlds. Throughout that limitless space two powers moved; mingled yet ever separate. One was a radiance that fructified, that gave birth and life and joy of life; the other was a darkness that destroyed, that drew ever from the radiance that which it had created; stilling them, hiding them in its blackness. Within the radiance was a shape of ineffable light and Kenton knew that this was the soul of it. In the darkness brooded a deep shadow, and he knew that this was its darker soul.

Before him arose the shapes of a man and a woman; and something whispered to him that the woman’s name was Zarpanit and the man’s Alusar, the priestess of Ishtar and the priest of Nergal. He saw in each of their hearts a wondrous, clear white flame. He saw the two flames waver, bend toward each other. And as they did so, shining threads of light streamed out from the radiance, linking the priestess with its spirit; while from the black core of the darkness threads of shadow ran out and cooled about the priest.

As the bending flames touched suddenly the shining threads and shadow threads were joined–for an instant were merged!

And even then, I’ve said nothing of the pulse pounding naval battles or the part where Babylonian gods ask a mortal man for counsel.

Yes, there are countless writer workshops on the topic how to create better action sequences, sure. Thanks to the internet, there is more information than ever available to people that want to infuse such things with greater historical accuracy.

But there are none on the topic of how men today have an entirely different notion of how their fictional characters would even begin to speak to their fictional gods. That the fan favorite pulp fantasy novel from before 1940 written by the man known then as the Lord of Fantasy would write something that was engineered in order to deliver just such an exchange is outside the scope of practically everything people conceive of fantasy as being today.

Don’t take my word for it that this book is absolutely amazing. Don’t react to my claims that there is nothing like this by scrambling to find a book that has a few superficial similarities.

READ THE BOOK FOR YOURSELF.

Immerse yourself in it. Turn off the part of your mind that is merely trawling for something to gainsay me with. See for yourself an artifact from a culture that has very nearly been erased from the collective consciousness. Step out of the frame of mind that you inherited from generations of people that were dead set on seeing this shabbily destroyed. Experience it for yourself. Bask in it. Steep yourself in it.

You won’t regret it.

Like your mention of what passes for new, clever or different is just something in lockstep with the current good think. Reading that was reminded of the trendy and edgy in late 80’s NYC, all of them different and unique in their uniform all black wardrobes.

“People today won’t just spontaneously write like A. Merritt, of course. Artists don’t get a yen to come up with things like the Virgil Finlay illustrations of his work either. And that impulse that drives people to do something ‘new’ or ‘clever’ or different is almost always in lockstep with culture. And the old books are expression of an entirely different culture.”

Before he ever began writing, Merritt had worked as a cub reporter in Philadelphia — one of the most corrupt cities in the US at the time — before spending time in Central America interacting with the locals and exploring ancient ruins. He came back, got married and quickly became an assistant editor for one of the biggest periodicals in the US. His life was — compared to many modern authors — too “white bread” and “square” while at the same time far more genuinely inquisitive. Merritt held a sincere interest in various exotic cultures around the world. They weren’t simply “vibrantly diverse” boxes for him to check off while simultaneously making them fit the dominant Narrative. All of that is just one reason why Merritt revolutionized SFF.

Merrit had LIVED before he started writing fiction. He’d been places — like Central America — where quarrels were still sometimes settled with blades and where there were no railroads, let alone automobiles. He had walked through serpent-haunted ruins. Merritt had eaten and laughed with people who were basically untouched by modernity. All of that came into play in THE SHIP OF ISHTAR.

Merritt was also the man who discovered and promoted Virgil Finlay, giving him the breaks that made Finlay a superstar in SFF circles. Burroughs may have loved J. Allen St. John’s art and had a great relationship with him, but Ed didn’t discover him.

“It’s like the difference between a dimensional shambler… and a crazy man wearing the hide of a dimensional shambler. ”

Excellent “The Horror in the Museum” reference.

“What then if someone from today wanted to write something “pulpy”? Most of the time you’ll get a caricature. Or a few things that are cherry picked from older works that are (again) held together by cultural touchstones that are entirely at odds with the way things used to be done.”

Ha, this reminds of when Michael Chabon edited an anthology that was supposed to be a pulp revival and a lot of the stories ended up being literary stories about characters having epiphanies while something vaguely adventure-ish happened around them.

And then on the other end, you have writers talking about how they’re making pulp because they wrote about vampires and werewolves fighting Nazis in space or whatever.

Read this book.

Actually, you should read as many of A. Merritt’s books as you can get your hands on, but if you only read one, read this one. There is a reason that fans voted it their favorite 75 years ago.

If you don’t like it, fair enough; to each his own. But if you feel for an instant a thrill to your sense of wonder, images you never dreamed of, and the subtle pleasure of a tale well told, remember this: someone tried to cheat you of this.

I SAW Merritt’s books in the spinner racks in the 70’s; they were everywhere. It was not chance, changing tastes or impersonal, irresistible trends that shoved his work down a memory hole; there was deliberate malice behind it.

Don’t let them win.

Now, READ damn it!

You’ve sold me on reading it.

-

AND! If you schedule a horoscope on it we’ll totally give that a signal boost too!

-

Making A.Merritt Great Again one reader at a time.

-

Whatever it takes.

-

“…so many people have never even heard of these books and these authors…”

That’s the sentiment I was going for when first asked by Deuce to write a guest blog post about A. Merritt for DMR Books.

Great post! The Ship of Ishtar was the first A. Merritt I ever read, and I’ve read it several times since.

I write my own brand of “pulp-style” stories but find myself often going back and toning down the purple prose which I guess I subconsciously sprinkle throughout. Many modern readers either don’t get it or don’t care for it. Any more, it seems it is often preferred that the author keep the story arc moving quickly; I try to strike a balance between minimalist and purply.

Check out the Merritt article if you wish; there are plenty of photos…

https://dmrbooks.com/test-blog/2019/1/20/you-collect-who