The Aristocrat by Chan Davis appeared in the October 1949 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. It can be read here at Archive.org.

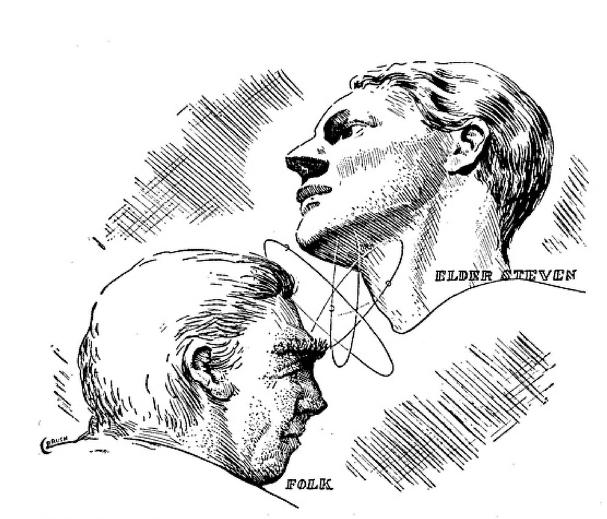

Someone forgot to remind Brush that Stevan is spelled with an A.

My next issue of Astounding begins promisingly enough with Chan Davis’ The Aristocrat. While it certainly falls into the category of “thinky stories,” this one manages to strike a balance between the actions and the thinks, though it’s front-loaded with the latter and takes a while to get to the former. It also manages to work a decent enough scientific puzzle into its thinks, while highlighting a struggle between rationalism and realism.

Set After the EndTM, The Aristocrat tells the story of Elder Stevan and the village he presides over. After the bombs and radiation, mankind diverged into two groups—the Folk, who were ignorant and savage but immune to the worst effects of the radiation, and the true Men, who were unmutated and retained the keen intellect of those who had lived in the City, but were weakened and sickly in the radioactive wasteland.

The Men set themselves up as curators of the old knowledge; they sought to guide the Folk, who they deemed as inferior but necessary to the survival of the human race, and act as lawgivers and holy men. They are the Elders. The story is told 1st person from the perspective of Elder Stevan, who has the misfortune of being the village elder at the time when the system collapses.

The only thing the Elder really has going for him is the reverence the Folk hold for his position; if that’s ever lost, things are over for him. Stevan needs to strike a balance when handing out his punishments for disobeyal that the perpetrators are sufficiently rebuked but not driven to desertion or further rebellion. When the story begins, a hunting/scavenging party has gone off without the blessing of the Elder; he’s obligated to punish them, but the party’s success accelerates the collapse of the system for three significant reasons:

Firstly, the party was more successful than anyone could’ve hoped and punishing success would drive a further wedge between the Elder and the community, even those loyal to him. Secondly, the party encountered wandering hunter Folk, likely descended from Folk who had left the village a generation previous, and won a victory over them. Thirdly, the party returns with a captive: a beautiful and, more importantly, healthy young woman who is Human and not Folk.

The Elder has the girl, Barbi, declared an Elder and takes her as his wife (Elder is relative; he’s like 30). She has all of the intellectual acuity of the Elders, but like the Folk, she is unaffected by the radiation that renders True MenTM feeble and sickly. While he teaches her from the books in the library, Stevan considers the genetic puzzle that could result in a healthy woman: a mystery which grows when Barbi bears him a child who is Folk at the same time that two of the Folk in the village give birth to a child who human. Stevan learns that the Folk had been giving birth to humans for years, but in the past they would usually kill them because they couldn’t survive the radiation anyway and previous Elders had commanded it.

To make matters worse for Stevan, after a year, all of Barbi’s reading has her woke and questioning the system that the Elders have in place:

“Let’s see what your excuses are for this ‘Elder’ business.” I swallowed hard, stood stockstill at the window. Her voice came clear and brisk from the shadows behind me and fell weirdly on my tired brain. “You want to save time, right? You don’t want civilization to have to start at the beginning again, you want to save time by keeping hold of the knowledge from before the War. But this isn’t the way to do it—keeping the Folk here as your slaves.”

Weakly, “The Folk aren’t slaves.”

“Some of them want to stay here,” she conceded. “But some of those would be dissatisfied if they thought they had alternatives. Look. You know what a civilized world’s like, you want to see one built. Well, if it’s done, it’ll be done by the people. You can’t just decide what it’d be nice to have happen. The men who are going to do it have to want to do it.”

Her earnestness frightened me; so I tried to sound amused and academic. “You seem pretty confident of your theory of history.”

That stopped her. She’d learned a lot in the last year, but she realized how much there was she didn’t know. “O. K.,” she said. “I’ll be specific. You might like the idea of a race of farmers, sticking peacefully to one place. But if there’s an easy living to be made by hunting, somebody’s going to take to the idea. If there’s an easy living to be made by raiding villages, somebody’ll take to that, too. Your books won’t stop them.”

Barbi leaves the village and rejoins the hunters, taking a number of the renegades from the village with her. There’s a pretty epic battle, where Elder Stevans digs up the last of the rifles from the bygone ages, and he and the remaining villages make a vigorous stand at the library in the early hours against the raiders. But it’s to no avail. The remainers are defeated, Stevans is knocked out and taken captive, and the library nearly escapes the torch.

What we end up with is a story about a woman who, after reading several books on history, science, and philosophy, decides to overthrow a Theocratic Technocracy and replace it with an anarcho-feudal system in which scholars will be slaves—keepers of knowledge, but with a stigma attached that would prevent them from setting themselves up as aristocrats. And it’s pretty rad.

While the story is a bit on the long side and is definitely a slow-burn, this is one I thoroughly enjoyed. Did it have action and heroics? Well, maybe not from the protagonist. But looked at as the view of a hero’s struggle against an oppressive social structure from the perspective of the system she is overthrowing, sure—Barbi’s definitely an action heroine. She’s not a “burn it all down” revolutionary, either. She understands the value that the knowledge which the Elders’ have kept has to offer. But no society can thrive dictated top-down, even with the best interests and best intentions. While Stevan tries to rationalize the importance of his position as a scholar and keeper of knowledge, Barbi is a realist: Men are equal in their creation, rights and freedoms, though not in their abilities and desires—best to accept these truths and allow men their opportunities to pursue their livelihoods as they see fit than to force and dictate to them how they should live.

Once again, we learn that nothing good ever comes of educating women…