Short Reviews – The House Where Time Stood Still, by Seabury Quinn

Friday , 23, June 2017 Uncategorized 10 Comments The House Where Time Stood Still by Seabury Quinn appeared in the March 1939 issue of Weird Tales. A scanned pdf of this issue can be found here at Luminist.org.

The House Where Time Stood Still by Seabury Quinn appeared in the March 1939 issue of Weird Tales. A scanned pdf of this issue can be found here at Luminist.org.

I’m sure that if I had the time and money to delve deeper into Weird Tales, I’d find myself wondering why and pontificating on the injustice that Lovecraft is one the only horror writers from that magazine who is still talked about. Seabury Quinn’s The House Where Time Stood Still is a damned creepy story that’s almost certain to give one nightmares. This is some real Cronenberg/Lynch stuff here, except decades before either of them. In fact, I hate that I have to use contemporary frames of reference to describe stories like this, because it should be the other way around.

Quinn’s story begins, more or less, with his famed Occult Detective Jules de Grandin explaining to his friend and Watson, Trowbridge, the philosophical differences between medicine as art (physicians/healers) and medicine as science (doctors); “followers of Aesculapius”… ”are concerned with individual cases” and “alleviating suffering in the patient”, while “the doctor, the learned savant, the experimenting scientist”… “cannot see [man the individual] for bones and cells and tissues where micro-organisms breed and multiply to be a menace to the species as a whole.” Needless to say, this conversation serves to foreshadow the villain of the tale, who embodies the worst attributes of the latter. If this were an English paper, I’d be more prone to also discuss the repeated references to Faust throughout, reinforcing the theme of the mystical vs. scientific, spiced with notions of damnation, predestination, unholy inevitabilities, and yes, also salvation, but I’ll suffice it to say it’s there.

Quinn serves up a clever misdirect, as Grandin is interrupted by the arrival of some copper pals from England. Some important dispatches from the embassy have gone missing along with the lad sent to deliver them; they hope to enlist Grandin and Trowbridge to look for the young man, last seen zooming off into the countryside in a conspicuous red hot-rod. Of course, this just serves to set-up the tale for Trowbridge to be in the right spot at the right time to fall into the hands of a megalomaniacal supervillain who’s been using an insane asylum as cover for his experiments in vivisection.

Doctor Friedrich Friedrichsohn was a brilliant surgeon during the Great War who also took some liberties with human anatomy. He was thought to have died in a mental hospital in Vienna, but he actually escaped:

“They had many things to think of when the empire fell to pieces, and they forgot me. I did not find it difficult to leave the prison where they’d penned me like a beast, nor have I found it difficult to impose on your credulous authorities. I am duly licensed by your state board as a doctor. A few forged documents were all I needed to secure my permit. I am also the proprietor of a duly licensed sanitarium for the treatment of the insane. I have even taken a few patients.”

Doc Freddy Fredson is a great villain, who is not only insanely evil, he is so dangerously genre savvy that he knows that he’s a Batman revolving-door-justice-system badguy:

“I’m not mad, really, but the general belief in my insanity has its compensations. For example, if through some deplorable occurrence now unforeseen I should be interrupted at my work here, your ignorant police might not feel I was justified in all I’ve done. The fact that certain subjects have unfortunately expired in the process of being remodeled by me might be considered grounds for prosecuting me for murder. That is where the entirely erroneous belief that I am mad would have advantages. Restrained I might be, but in a hospital, not a tomb. I have never found it difficult to escape from hospitals. After a few months’ rest I should escape again if I were ever apprehended. Is not that an advantage? How many so-called sane men have carte blanche to do exactly as they please, to kill as many people as they choose, and in such manner as seems most amusing, knowing all the while they are immune to the electric chair or the gallows? I am literally above the law, mein lieber college.”

So, what sort of horrible experiments does the good Doctor Fred perform? One of the most horrific set pieces in this tale is revealed when, after Trowbridge hears some melancholic strains of violin from upstairs, Freddy recounts the story of a woman who spurned him and her lover:

“When I was at the university before the war”—his voice had the hard brittleness of an icicle—“I did Viki Boehm the honor to fall in love with her. I, the foremost scientist of my time, greater in my day than Darwin and Galileo in theirs, offered her my hand and name; she might have shared some measure of my fame. But she refused. Can you imagine it? She rebuffed my condescension! When I told her of the things I had accomplished, using animals for subjects, and of what I knew I could do later when the war put human subjects in my hands, she shrank from me in horror. She had no scientific vision. She was so naïve she thought the only office of the doctor was to treat the sick and heal the injured. She could not vision the long vistas of pure science, learning and experimenting for their own sakes. For all her winsomeness and beauty she was nothing but a woman. Pfui!” He spat the exclaimation of contempt at me. Then:

“Ah, but she was beautiful! As lovely as the sunrise after rain, sweet as springtime in the Tyrol, fragile as a—“

“I have seen her,” I cut in. “I heard her sing.”

“So? You shall see her once again, Herr Doktor. You shall look at her and hear her voice. You recall her fragile loveliness, the contours of her arms, her slender waist, her perfect bosom—see!”

He snatched the handle of the door and wrenched it open. Behind the first door was a second, formed of upright bars like those of a jail cell, and behind that was a little cubicle not more than six feet square. A light flashed on as he shoved back the door, and by its glow I was the place was lined with mirrors, looking-glasses on the walls and ceiling, bright-lacquered composition on the floor; so that from every angle shone reflections, multiplied in endless vistas, of the monstrous thing that squatted in the center of the cell.

In general outline it was like one of those child’s toys called humpty-dumpty, a weighted pear-shaped figure which no matter how it I may be laid springs upright automatically. It was some three feet high and more than that in girth, wrinkled, edematous, knobbed and bloated like a toad, with a hide like that of a rhinoceros. If it had feet or legs they were invisible; near its upper end two arm-like stubs extended, but they bore no resemblance to human pectoral limbs. Of human contours it had no trace; rather, it was like a toad enlarged five hundred times, denuded of its rear limbs and—fitted with a human face!

Above the pachydermous mass of shapelessness there poised a visage, a human countenance, a woman’s features, finely chiseled, delicate, exquisite in every line and contour with a loveliness so ethereal and unearthly that she seemed more like a fairy being than a woman made of flesh and blood and bone. The cheeks were delicately petal-like, the lips were full and sensitive, the yes deep blue, the long, fair hair which swept down in a cloven tide of brightness rippled with a charming natural wave. Matched by a body of ethereal charm the face would have been lovely as a poet’s dream; attached to that huge tumorous mass of bloated horror it was a thousand times more shocking than if it too had been deformed past resemblance to humanity.

Friedrichson had removed Viki’s arms and legs and infected her with virulent elephantitis. He turned the woman who rejected him into a blob monster, stuck her in a room where she was forced to constantly see her misshapen body, and occasionally will use a cattle-prod on her lover to force her to sing.

Quinn manages to bring the story full circle when it’s revealed that the lad from the embassy with the dispatches has not gone AWOL and sold the intelligence to foreign powers, but has fallen, along with a gorgeous dame, into the hands of the mad doctor. Friedrichson’s ultimate experiment is to determine what combination of face, body, and personality human attraction springs from. So, he’s been keeping the couple together, letting them meet, and then knocking them out with sleeping gas repeatedly, so that they’ll fall in love. Once he’s certain that the couple is in love, he’s going to do to them what he’s done to Viki, sticking them in a large mirror room together where they’ll be forced to see how hideous they are. He reasons that if the couple are still in love and not completely repulsed by one another, he can rule out the body as the source of attraction; if they are repulsed, then the body is more important than the face or personality.

So, yeah, next time someone says “pulps are just kids’ stuff”, tell em to read this one.

Holy angels, in heaven blest,

My spirit longs with thee to rest…

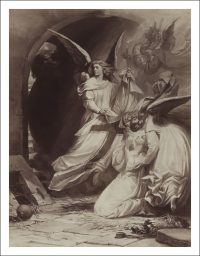

Sounds interesting. I love the end picture.

-

The ending pic there is actually one of the Kreling engravings from Faust, depicting the angels receiving Margaret in the scene alluded to in the story. It wasn’t in Weird Tales, but it’s a great piece and a great scene, so I thought I’d toss it in.

That is quite different from those few de Grandin stories that I’ve read in the past. It’s the sort of scenario you’d expect to find in contemporary bizarro horror fiction. I do like the underlying message he seems to be going for there, too.

One of Seabury Quinn’s creepiest efforts.

Thanks for posting this one. I know that some people don’t like his de Grandin stories, but some (like this one) are quite effective, and great for ideas for any Call of Cthulhu campaign that doesn’t want to spike the Sanity meter every session.

Indeed, this sounds like an early version of body horror, so the comparison to Cronenberg makes sense.

Intriguing stuff; will give it a shot.

I’ve never read this particular story, but it interesting to point out how HPL thought that Quinn could’ve been one of the finest writers of his generation. Most of the time though, he wasn’t even trying, given that he kept churning out prodigious amounts of text with easy money being his only goal. So, with him you have flashes of brilliance in this ocean of muck.

I read this tale once when I was a teen in a book my father has. Still remembering it years later. =-P