Short Reviews – The Seal Maiden, by Victor Rousseau Emanuel

Friday , 5, January 2018 Uncategorized 2 CommentsThe Seal Maiden, by Victor Rousseau Emanuel originally appeared in the Nov 13, 1913 issue of ”The Cavalier”. It was reprinted in the February 1950 issue of A. Merritt’s Fantasy Magazine. It can be read here at Archive.org.

Okay, one of the more knowledgeable old-timers here at Castalia needs to help me out. There has to be some sort of encapsulating descriptor for “Story that uses a fairytale/old wives’ tale/local legend as a framing context for a story that parallels those tales in certain significant thematic ways while the truth of those tales is never confirmed nor is the magical element presented in greater magnitude than ‘mysterious’ and ‘elfin’ attributes of places, events, and people within said story.” Because that’s what we have here in The Seal Maiden.

The story is prefaced with a brief explanation of the local legend on Grand Miquelon that seals had once been human, and if a seal woman can win a mortal’s love she can regain a soul. Seal hunters try to avoid killing young seals before killing the mothers; if they do have to kill a mother after they’ve killed the babies, they avoid looking in the mother’s eyes so as not to become bewitched.

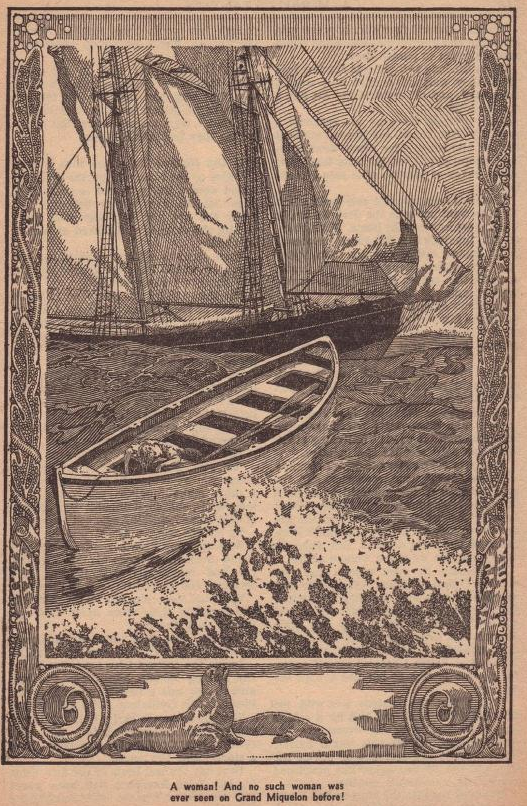

The tale begins in earnest when one seal hunter, Pierre, fails to kill a mother seal after dispatching her young—its sad cries and the mournful look in its eyes cause him to stay his hand. On the hunters’ return, they come across a small boat with a lone, castaway woman in it. Much to the dismay of Pierre’s wife (to whom he’d only been married a few days before the expedition), the hunter brings the strange woman into their home—where she gives birth to a daughter, Marie, then expires. Pierre dies of illness around the time of the next seal mating season, leaving his wife to raise little girl alone , until she too dies, at which point little Marie gets handed off to the cruel mother of Pierre’s hunting partner, Jean, with whom he’d found the strange woman.

What ensues is a romance and bitter love triangle; the elfin girl Marie is in love with a local crippled boy, Achille, who is seen as useless but has talents in song and music, while Jean has become obsessed with the young beauty. The curate has been something of a surrogate father to Marie, so Jean approaches him about getting Marie’s hand in marriage. The curate admits that it’s near time she should marry and would be well provided for; the girl acquiesces (“If you wish it, father”), though she plans to run away with the crippled boy. Jean finds them together, he flips, attacks them, and gets himself superficially injured when Marie fights back.

Jean wants “justice” for the attack, so to press the case, the governor is brought in. The governor, a Parisian, is a romantic sort, thinks Jean’s a fool, and he sympathizes with Marie, who he immediately recognizes is unhappy with the idea of marrying Jean. Additionally, Marie may actually be the grand-daughter of a very important and wealthy fellow—the governor recognizes the man in the painted image within the locket that Marie was bequeathed by her mother at birth. He’ll need to bring his friend to confirm in person, but in the meantime the governor will fix Achille up with a share on a fishing boat and will allow Marie to remain with the Curate until spring, when she will be able to marry Achille. Of course, he stipulates “There must be no more stabbing.”

When her love’s boat is late in returning, Marie remembers the words of Jean’s mother, the admonishments to cast away her fairy charm else she never find a lover. Marie throws the locket into the sea. She doesn’t care about the wealth and privilege of having a noble father whom she’s never met; all Marie wants is the return of her beloved Achille. When the man arrives, certain he must have found his long-lost daughter, promising her all the splendor of Europe, Marie rebuffs him, insistent that he is not the man in the locket. Marie leaves the pleading gentlemen to find that Achille’s boat has at last come in. The tale ends thusly:

“[Marie] looked at her lover and knew that the seal soul, the restlessness of the human heart, was dead at last. All life was here, in Achille’s arms, on Miquelon.”

This is as close as the story ever comes to accepting a magical premise as true, and notably it is such that it can still be interpreted as the character’s own belief and acceptance of truth as filtered through the superstitions ingrained upon her in childhood. All throughout the story, the supernatural and fantastical elements can all be chalked up to superstition and coincidence, but the nature of romance allows for just enough wiggle-room to wonder “but what if?”

The “fantasy” of The Seal Maiden is a far cry from the “horns of elfland”. Indeed, the lead-in teases much more explicitly than Victor Rousseau concedes in the text itself:

“Had mortal love endowed her with a soul, as legend had foretold? And must she now live forever tormented by that poignancy of grief that only the indestructible can know?”*

It is a fairytale with more real than magical realism, yet there is a subdued magic all throughout. And it’s because of that “what if?”, whereby faith in the old stories and belief in the old wives’ tales may grant one access to secret truths and a small degree of mystic control over one’s tiny piece of the universe. Magic or no magic, it sounds like a story that could happen, and should it happen by a touch of magic, how much more wonderful and splendid our world is for it?

*Somebody slap me if I ever write a lead-in that bad.

There’s some superficial resemblance to the animated film “Song of the Sea” here, but that’s focused on selkies and Irish myth….stilll….