Short Reviews – The Vanishing Venusians, by Leigh Brackett

Friday , 13, October 2017 Uncategorized 2 CommentsThe Vanishing Venusians by Leigh Brackett appeared in the Spring 1945 issue of Planet Stories. It can be found here at Archive.org.

I almost wonder if Peacock was going for a theme, running two stories with plant-aliens in a row. While the Sorogasters of Rocklynne’s Sandhound story are truly alien in both form and behavior, Brackett’s plant aliens are uncanny, bearing a strong enough resemblance to humans that their physical differences and behaviors are menacing and horrific.

I almost wonder if Peacock was going for a theme, running two stories with plant-aliens in a row. While the Sorogasters of Rocklynne’s Sandhound story are truly alien in both form and behavior, Brackett’s plant aliens are uncanny, bearing a strong enough resemblance to humans that their physical differences and behaviors are menacing and horrific.

The aliens of Brackett’s The Vanishing Venusians are elves. Not Vulcan homo-superior Space Elves, but weird and creepy Fey Elves (in space!).

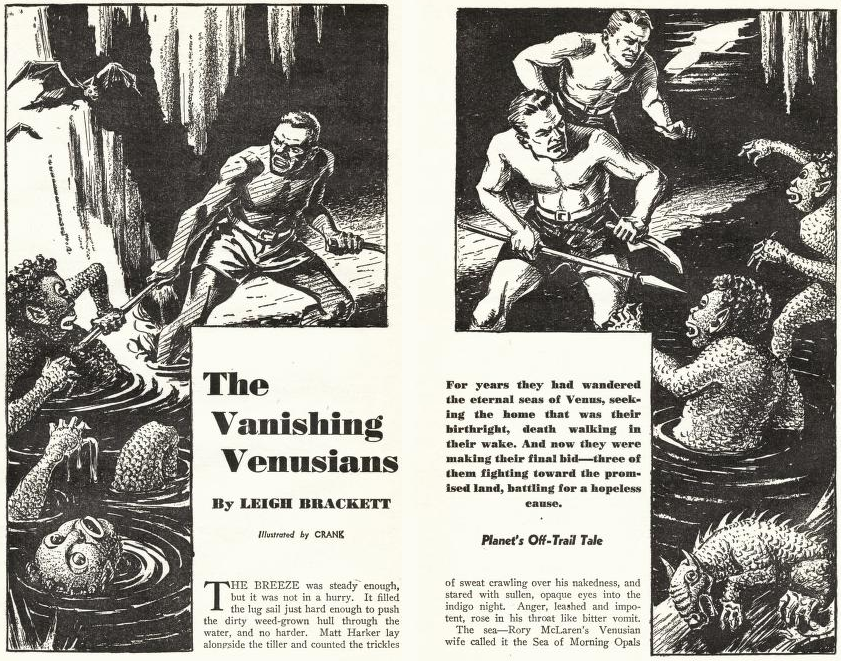

A ship of human colonists on Venus are trying to find a new home on the swampy planet. Many are getting sick, dying and desperate as they sail the Sea of Morning Opals in search of a new home. Matt Harker, one of the first generations of colonists, Rory McLaren, a young expectant father with a native wife, and Sim, a spiritual-singing sailor, go off to explore the land they’ve spotted. Many colonists are pessimistic about the chances (everywhere they’ve found has been swamp and mud, breeding-grounds for fever), but McLaren is desperate for his family’s sake. If there’s good arable land on the plateau, they may be able to finally settle. Unfortunately, the land is already inhabited by “plannies”—the strange plant-animals that are native to Venus.

The Vanishing Venusians is a story in the sub-genre of fantasy wherein the world of man and fey collide, the boundaries of fey are inevitably pushed back and a little bit of magic leaves the elder world. C.L. Moore’s Daemon, Dunsany’s The Charwoman’s Shadow, and Swann’s The Weirwoods are all examples of such tales, however Brackett does things a bit different by setting her story on an alien world and treating the fey element as implicit rather than explicit while still highlighting the moral fulcrum upon which such elf-stories rest. The Vanishing Venusians is about a conflict between goblins, elves, and men.

The first group of plannies the trio encounters, “the Swimmers”, are the goblins: a human-looking combination of fish and flower that accost them as they ascend the plateau via underground tunnels.

They were agile and graceful. There was something unpleasantly childlike about them. There were fifteen or twenty of them, and they reminded Harker of a gang of mischievous kids—only the mischief had a queer soulless quality of malevolence.

The trio has to fight them off–McLaren gets hurt badly, and Sim makes a big-damn-hero sacrifice so that Harker can get McLaren to safety.

It’s later revealed that this tribe had once held plateau but had been driven back into darkness; despite their similarities, there’s an ancient acrimony between these deep elves of the caves and the high elves of the plateau.

The second group of plannies are the elves: flawlessly beautiful and strangely perfect naked beings who live harmoniously with nature and communicate telepathically. These are even more uncanny than the cave plannies—Harker begins falling for the planny he’s named Button, but he knows something’s dreadfully wrong about them. They can’t understand why he’d help McLaren—he’s “spoiled”, “broken”, “finished”, and “useless”—and Harker wakes up the next morning to find they’ve tossed his still-living-but-injured friend into their compost heap.

For mankind to find its place, the fey must be driven from elf-land, and Harker and Button realize it about the same time:

Button’s spoken thought cut across the image. “I have seen your thoughts, some of them, since the moment you came out of the caves. I can’t understand them, but I can see our plains gashed to the raw earth and our trees cut down and everything made ugly. If your kind came here, we would have to go. And the valley belongs to us.”

Matt Harker’s brain lay still in the darkness of his skull, wary, drawn in upon itself. “It belonged to the Swimmers first.”

“They couldn’t hold it. We can.”

“Why did you save me, Button? What do you want of me?”

“There was no danger from you. You were strange. I wanted to play with you.”

“Do you love me, Button?” His fingers touched a large smooth stone among the fern roots.

“Love? What is that?”

“It’s tomorrow and yesterday. It’s hoping and happiness and pain, the complete self because it’s selfless, the chain that binds you to life and makes living it worthwhile. Do you understand?”

“No. I grow, I take from the soil and the light, I play with the others, with the birds and the wind and the flowers. When the time comes I am ripe with seed, and after that I go to the finish-place and wait. That’s all I understand. That’s all there is.”

He looked up into her eyes. A shudder crept over him. “You have no soul. Button. That’s the difference between us. You live, but you have no soul.”

After that it was not so hard to do what he had to do. To do quickly, very quickly, the thing that was his only faint chance of justifying Sim’s death. The thing that Button may have glimpsed in his mind but could not guard against, because there was no understanding in her of the thought of murder.

Harker has to kill the princess of elf-land and set the goblins to take their revenge on the elves only to be destroyed by the light of day (it’s an albino-cave species thing, but it works as a great metaphor too) so that McLaren can get away, get back to his pregnant wife, and let the colonists know they have a safe place waiting for them.

So, there are a lot of fascinating things about this piece.

First of all is the character Sim. He’s a black character whose significance in the story is not his race, but his spirituality. He’s introduced to us relieving Harker’s shift on the tiller, singing “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” in the early pre-dawn hours. The line Brackett specifically singles out: “Oh, I looked over Jordan, and what did I see, comin’ for to carry me home.” There’s a lot in this line that works as double entendre: like the Israelites, the colonists have been displaced and wandering, looking for a new home—Harker has just said “[he] was there when this trek to the Promised Land began, back on Earth, and [he’s] still waiting for the promise.”

Sim goes out not just in a blaze of glory, but as a spiritual and righteous man against godlessness:

Sim was singing again. The sound grew fainter, diminishing downward in the distance. The words were lost, but not what lay behind them.

Ultimately, it’s Sim’s faith that is juxtaposed with soullessness of Button and the elf-plannies that grants the story its elf-land context. The thought of Sim’s faith and Sim’s sacrifice weighs on Harker when he’s with the mysterious and alluring Button. Sim was a man who would sacrifice himself for his friends; Button and her people cannot see beyond themselves in the here and now.

While Sim isn’t exactly a proto-Stark, I think it’s noteworthy that he’s an African American sci-fi character in the pulps whose race is neither his defining characteristic in the story or to the characters around him. That’s not to say it’s entirely incidental (like the no-big-deal-it-is-what-it-is interracial couple in The Spider-Men of Gharr) or that it doesn’t shape him in the story; before setting out, a minor character asks him why they’d “want to do all that climbing, maybe to no place”, to which he replies “that’s what my people always done. A lot of climbing, to no place.” If anything, what defines him is his faith and spiritualism paired with his strength and courage that allow his companions to find and settle in the Promised Land, even if he himself will not be able to cross the Jordan, so to speak.

Were the plannies “elves”? No–they were an analog of elves. And therein lies the brilliance. While they were not explicitly fey, their nature raises questions about the soul, the source of morals and morality, and what sets humans apart from animals. Though I’ve encountered several examples of space elves (Vance’s Sacerdotes and Uldras come first to mind), those typically tend to be transplants of more modern fantasy elves; the Vanishing Venusians is one of the few examples I’ve seen so far of classic pre-genre elves transplanted into a science fiction setting. The kind of story Brackett tells here is far more akin to something out of Thomas Burnett Swann’s romances of mythic antiquity than what you’d normally find in the pages of Planet Stories.

Lastly, there are a few easter eggs for Bracket fans in regards to her Venus setting. Though it changed and evolved a good bit throughout her stories, there are a number of elements that carry over and across several titles. The Venusian dragons make a brief appearance here (ones would later show up in The Moon that Vanished and as a pet of the youngest Lhari in Enchantress of Venus). Additionally, the reason that the colonists are wandering the seas looking for a new home is that their first settlement was destroyed by the Cloud People; the Cloud People are briefly cited in Enchantress of Venus as the tribe from which the Lhari descended—sounds like they’ve always been a cruel lot!

Brackett did weird and creepy Fey elves (in SPAAAAACE!) on Mars, too.

“Though I’ve encountered several examples of space elves (Vance’s Sacerdotes and Uldras come first to mind), those typically tend to be transplants of more modern fantasy elves…”

As HP noted, Brackett utilized elf-analogs of various kinds in other tales, right up through her BOOK OF SKAITH. However, Poul Anderson was probably the king of “space elf” SF authors. He had all kinds of analogs, from JRRT-style to only vaguely humanoid “feys” in FIRE TIME and “The Queen of Air and Darkness.” CJ Cherryh likes her space elves as well, but they tend to be somewhere on the SILMARILLION-BROKEN SWORD continuum. She keeps her wild fays in her fantasy fiction.