Son of the Pulps Part 2: Farmer’s Tarzans

Saturday , 10, June 2017 Appendix N, Authors, Book Review, Fiction 6 Comments

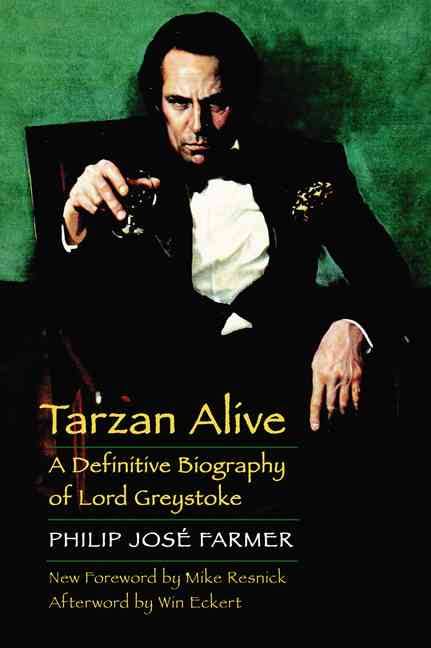

Such an awesome cover that I reused it from last week!

Tarzan as imagined by Edgar Rice Burroughs is a vivid hero that epitomizes full-blooded adventure and influenced generations of writers. The Tarzan of Jose Philip Farmer is better; the ultimate, indomitable hero and my favorite fictional character. As we noted in last week’s column, Farmer was utterly fascinated with Tarzan and wrote several different pastiches of him, involving everything from the linguistics of his adoptive, beastly mother to Tarzan traveling back through time itself. Let’s briefly look at each one and note the differences between the Burroughs original and the Farmer version.

The Tarzan (James Grandrith) of A Feast Unknown-

As a reader on last week’s column noted, this is a book with lots of extreme content! Originally released by a publisher whose other books were all porn, this adventurous work is filled to the brim with graphic, copious bloodshed and sex. It’s also downright bizarre; there are five instances of rape in the work, of which only one is man on woman. (That one, by the way, was perpetrated by Jack the Ripper on the mother of Tarzan and Doc Savage) The others are man on beast, woman on man, man on man, and beast on woman. That last one, incidentally, is utterly comedic.

While those who haven’t read A Feast Unknown likely consider it insane (it is!), this shouldn’t detract from a small point. Which is that the book is absolutely fantastic; as exciting, action-packed, and visceral a yarn as I’ve ever come across. Nevertheless, before we delve into this iteration of Tarzan, it’s fair to ask what Farmer’s motivation here was, as he would never write anything like this again.

To find the answer, we must know a bit more about Farmer’s life. See, Farmer had written the classic short story The Lovers in 1952 and been offered $4,000 and a book contract by a publisher, so he had quit his job to become a full-time writer. Unfortunately, the publisher screwed him and never ended up giving Farmer a penny. As a result, Farmer had to go back to the drudgery of a regular job, that of technical writer. He did this for fourteen whole years, until finally, following the success of Riders of the Purple Wage, he again became a full-time author in 1969. A Feast Unknown was his first book after this.

It was a jubilant, intentional bridge-burning. Farmer made it clear that he never, ever wanted to go to back to technical writing or any other job that wasn’t fiction. He put every bloody, sexual, and ribald element he had ever wanted to during a decade and a half of boring write-ups.

His Tarzan, too, is the most different from Burroughs’ work. “Grandrith” is not an altogether human entity; his emotions and reactions are of a more savage, primal kind. He doesn’t feel many typical human reactions or revulsions, allowing him to survive his harsh environment. Neither is this Tarzan a beast; he is a unique entity.

Towards this end, Tarzan mentions he has engaged in cannibalism and is not the least bit ashamed of this fact. I personally like this wrinkle, since the “taboo” Burroughs invokes in Tarzan of the Apes never made sense to me. Tarzan has survived in a savage jungle his whole life, and has regularly eaten the flesh of fallen foes he has slain, regardless of what kind of beast they are. Why should this particular slain beast, who had killed his dear adoptive mother, and who doesn’t look like him (Tarzan being English and the tribesman being African) be any different?!

In fact, in A Feast Unknown, narrated from Tarzan’s first-person perspective, he chides his “biographer” as a well-meaning but often naive man;

He was a romanticist and, in many ways, a Victorian.

He would have made up a story of his own, ignoring the real story, as he did with so many of my adventures. He was interested mainly in adventure for its own sake, although he did describe my psychology, my Weltanschauung. However, he never really transmitted the half-infrahuman cast of my mind.

Perhaps he could not understand that part of me, although I tried to communicate it as well as I could. He tried to understand, but he was human, all-too-human, as my favorite poet says. He could never grasp, with the human hands of his psyche, the nonhuman shape of mine.

There is other disagreement with his famous biographer. For instance, Tarzan’s famous adventures in Opar, the golden city where he attracts the love of the high priestess, are debunked in a hilarious, slightly rude manner;

The topography resembles that described by my biographer as the site of the lost city which contained a secret underground chamber full of gold and jewels. My biographer also described the lovely high priestess of the sun cult of the degraded locals and her unrequited love for me. The basis for this romance was an actual ruined city. Or, I should say, about four acres of tumbled stone under earth and some stones uncovered by wind now and then, part of a wall, and the six foot high stub of a tower. It resembled the ruins of Zimbabwe in South Rhodesia. About four dozen people lived among the ruins in wattle-and-mud huts.

With their peppercorn hair, yellow-brown skin, epicanthic folds, and tendency to female steatopygia, they resembled Bushmen. They may have been descended from the builders of the original city. They called the ruins remog, meaning, father-stones. They spoke a language unrelated to any other, as far as I know.

In 1911, during one of my long wandering journeys across Africa, I found this valley and the ruins. I did some preliminary digging at random, and when I found a gold bracelet and a gold figurine not six inches below the surface, I named this place Ophir, after the Biblical city of treasures. I returned with some equipment a few months later and made some deep cuts. I found no more gold, although I did discover broken pottery, a few beads, some carved ivory, and some impressions of weapons which had left a bronze residue. I also found some primitive gold melting and refining equipment.

Later, he describes the alluring woman whose heart he captures;

The shaman of the tribe was a young female whose face was not too unpleasant. She had enormously fat buttocks and full uptilting breasts. She also had a very large vagina and may have been disappointed in the ability of the males to fill her. She came to me that night and dismissed the guards. I was not very responsive, but she sucked on me and worked me up to a full erection. After this, she sat down on me and bobbed up and down like a balloon on a string until we both had come. This went on all night until just before dawn. I fell asleep for a while and awoke with a piss hard-on. A fly landed on my sensitive glans and precipitated another ejaculation. It was caught in the first spurt and died. I have never forgotten that. It may be the only one in the history of flies to have died in this manner.

While he would be less blunt about it in future iterations of the character, Farmer would frequently chide Burroughs as shying away from the earthy, often vulgar realities of the Tarzan character.

Keeping this in mind, it’s notable that Tarzan is more clever and well-educated than the one Burroughs wrote of! His knowledge of human science, culture, and history is exceptionally rich. He is a researcher and occasional lecturer at a British university. He can speak a multitude of languages. And while the Burroughs original showed a certain naivete, allowing himself to be hoodwinked by Rokoff time and again, this one has a deep knowledge of human nature, outsmarting and fooling more devious men than the Russian count time and again. This would be another element kept throughout Farmer’s Tarzans.

And it should be noted that Grandrith still retains many of the characteristics Burroughs wrote of. He is an exceptionally brave, moral creature, never taking the life of an innocent (although this one has few qualms about brutally killing villains!), and going out of his way to protect ordinary, decent humans weaker than himself, especially women.

This more savage, hyper-intelligent Tarzan appeals to me tremendously, and seems more in keeping with the African jungle environment he survived. The Burroughs character is often too much of a typical Victorian hero, with a typical Victorian’s mindset and morality.

The Tarzan (James Grandrith) of Lord of the Trees, sequel to A Feast Unknown-

Interestingly, there is some difference in the Tarzan in the very next entry in the Empire of the Nine series Farmer wrote! The extreme elements of its predecessor are eliminated or severely toned down and there isn’t the same satire as we saw with the story of Opar. Burroughs is still chided as a Victorian-minded biographer who didn’t fully understand his subject, but in a more loving manner.

For instance, it’s noted that Tarzan never emits the ridiculous yodel made popular in the early Hollywood films. This makes sense; why would a skilled, silent hunter warn his prey? And he ridicules the idea that he would ever swing on vines. After all, they are liable to give way under Grandrith’s large, muscular frame, and a fall from that height would kill even him.

Most significantly, this book depicts Tarzan in all his survivalist glory. Faced with a skilled mercenary army tracking him down in an African jungle, our hero is a stealthy shadow, eluding and killing them. He is also able to live off the land, eating insects and roots if need be. Incidentally, Grandrith notes that a normal human would have died eating the same diet he had in his adopted home. However, Tarzan has special genetic gifts inherited from a certain demigod ancestor, from an immune system impervious to regular disease to bones 1.5 times thicker than that of humans.

I love this depiction of the character. It occasionally appears in the original Burroughs works, and is Tarzan at his best. Here, it’s the sole emphasis of the book, and is expanded and enhanced.

There is a third book in the excellent Empire of the Nine, The Mad Goblin, but it is chiefly concerned with Tarzan’s half-brother, a pastiche of Doc Savage.

The Tarzan of Tarzan Alive and related writings-

The book is very much a meticulous labor of love. In addition to introducing his Wold Newton, there is an abundance of great material on Tarzan. Farmer examines the precise linguistics of the “folk” who raised Tarzan, arguing, as he had in the previously examined books, that they weren’t quite apes. The primary reason being that humans who aren’t exposed to any human language by the age of about 5 never learn to talk. How then, is Tarzan an exception? Farmer argues that the folk had a rudimentary language and gives a detailed analysis of what it would sound like, and even its grammatical rules!

There is also a transcript of the interview Farmer conducted with Tarzan that he talks about here. As well as an analysis of Tarzan’s family tree. And, particularly amusingly, Farmer briefly examines all the books in the Tarzan collection.

This Tarzan, unlike Farmer’s previous one, has never engaged in cannibalism. Although Farmer, with his attention to detail, comes up with a more plausible reason than a deep, hidden voice within Tarzan’s ancestry. And reiterates the inaccuracy of Tarzan’s famous whoop and the suicidal concept of swinging on vines.

Incidentally, this Tarzan once made his way to Hollywood to try out for the film role of Tarzan. Only to be rejected by the producers for being inauthentic!

This book is a treasure trove for any fan of the character.

The Tarzan (John Gribardsun) of Time’s Last Gift–

In this iteration, more than all the others, we see an element of sadness to the great hero. Tarzan barely feels human. But here, he is more a wise, savage demigod who resembles a pagan god of the hunt. Indeed, since he travels back in time to the beginning of humanity, it’s noted that the legendary characters Apollo, Hercules, and Gilgamesh are nothing more than stories of Tarzan!

And living so long, and seeing so many people he loves and cares for die, makes Tarzan a sad, almost tragic character.

While this makes Gribardsun vulnerable, and in many ways, all too human, he is also a timeless hero who has seemingly conquered death itself. I doubt most readers will experience the same sensations I did, but even thinking about it now, my hair stands up on end.

In many ways, with his epic ending, Farmer succeeded in immortalizing Tarzan. As long as people have amazing stories about him to read, like in Time’s Last Gift, the character will continue to live on. He too will have conquered death, like Gribardsun.

Hopefully, with this analysis, I have conveyed some of the greatness of Farmer’s Tarzans, and the ways in which he differs from the original. I encourage readers to check out all the books mentioned here. At the very least, they are thrilling, fantastic adventures.

What about Farmer’s THE DARK HEART OF TIME? He finally achieved his wish of writing an actual Tarzan novel.

I would heartily recommend PJF’s Khokarsa/Opar novels. He plays it straight and I’m fine with counting them as Tarzanic semi-canon. Carey has continued the series quite well. Great, pulpish fun.

-

To me, it was good, but not great. Plenty of ERBian/Wold Newtonian Easter Eggs. I would rather read the PJF/Carey Opar books, honestly.

-

I enjoyed his Khokarsa novels and have re-read them a few times. I thought Farmer balanced the world building and action aspects very nicely there. Carey’s follow-ups were quite worthy successors too.

Time’s Last Gift was, in retrospect, a quietly epic piece and the ending has become something of a favorite of mine. The connection with Khokarsa was also well done.

Uggghhh…