SUPERVERSIVE: “Futurama” explores the big ideas while avoiding message fiction

Tuesday , 18, October 2016 Fiction, Superversive 7 Comments

From left to right: Fry, Bender, and Leela

There will be spoilers to endings of episodes. The subject of the post happens not to depend so much on twists, but even so, I recommend watching the show first before reading my review. In any case, all spoilers here on in are unmarked. You’ve been warned.

The more I think about it, the more I lean towards the conclusion that “Futurama” is not only superversive, it is one of the most superversive shows ever made. “Futurama” is the anti-“Rick and Morty”. Some episodes even share similar concepts in broad strokes – like, for example, the dual classics of “The Late Philip J. Fry” and “Rick Potion #9” (if you don’t see it, check out my original “Rick and Morty” article) – while somehow managing to end up almost completely opposite in tone and message.

In its prime, I think you could make the argument that “Futurama” was one of the funniest shows in television history; I defy you to find the man who can watch “Roswell that ends well” without cracking up. Even so, there are a lot of funny shows out there. What makes “Futurama” consistently different is that it nails its moments of sentiment and emotion. I don’t think I’ve ever seen ANY show this good at making me care about its characters. “Luck of the Fryrish” (which actually made me tear up, something I never do), “The Sting”, “The Devil’s Hands are Idle Playthings”, and “Meanwhile” all manage the trick with astounding success, among others.

(We will not speak of “Jurassic Bark”.)

For all of the superversion of the show, one episode really impressed me not just with its superversion, or with the cleverness of its scientific conceit (as with episodes like “A Prisoner of Benda”, “The Late Philip J. Fry”, or, again, “Roswell that ends well”), but with the intelligence and maturity that was necessary to pull off its ambitious premise successfully. That episode, as I’m sure fans of the show can probably guess, is “Godfellas”.

Bender, realizing he has worshipers

And seriously, what an ambitious premise. Remember “Bruce Almighty”, the Jim Carrey comedy about a man who gains the power of God, but only in his home city? It was a mildly amusing movie with an incredible amount of potential that it never quite lived up to. As Tom Simon pointed out in that treasure trove of brilliance, “The taste for magic”, if “Bruce Almighty” actually took the opportunity to seriously explore what it would be like to be God and not pause for things like jokes about the size of Jennifer Aniston’s breasts, we could have seen something truly transcendent. The creators of Superman had a similar opportunity that they lost after a foolish comics editor foisted kryptonite on an unassuming public. Both hint at the potential of a story about a man with the power and responsibility of God, but neither commit to the extent that they should, and the results end up disappointingly lackluster.

“Godfellas” is the take on that concept that “Bruce Almighty” should have been. Not that there aren’t any jokes, but brevity is the show’s friend here: Even the jokes are part of the show’s attempt to seriously explore what it would be like if a normal human being (Bender might be a robot, but he has more humanity than most humans) had the awesome power of God.

The plot: After an attack by space pirates, Bender the robot is accidentally shot off into deep space, presumably never to be seen again. While flying through space he goes through a small asteroid field and inadvertently hits a rock populated with tiny people known as the Shrimpkins, who colonize Bender’s body and worship him as a God.

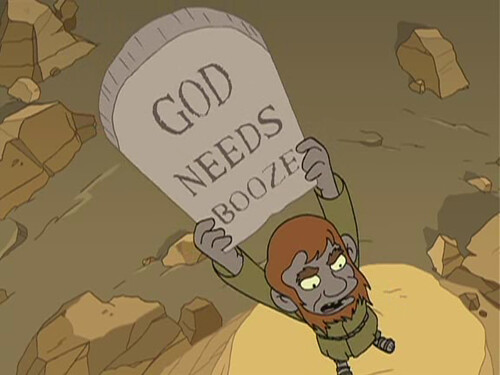

Bender makes “Leviticus” a little easier for the Shrimpkins

At first, Bender is delighted, and uses his newfound Godlike influence to issue “The One Commandment” (“God needs booze”). The Shrimpkins work diligently to create “The Great Brewery” – but all is not as it seems. As the prophet Malachi explains, building the brewery has maimed many of them, the gases emitted from it polluted their air and, of course, it attracted organized crime to the area.

A guilt-ridden Bender attempts to answer the Shrimpkins prayers for rain, sun, and wealth, but only makes their lives worse in the process. He tells the Shrimpkins that he is done helping: They will have to take care of themselves.

Later, Malachi petitions Bender again for help. The Shrimpkins living on Bender’s backside are “atheists” and don’t believe in him, and have started a war with the believers on Bender’s front. Bender refuses to intervene, but to his horror the atheists gain access to his nuclear stockpile. In the ensuing war the entire colony of Shrimpkins, believers and atheists, is decimated in a nuclear strike, and Bender is once more left to drift through space alone.

This scene is one of the best “Futurama” has ever done, mixing humor, horror, and pathos in a way the show never quite achieved again. The saga of the Shrimpkins is totally absurd, and the show knows it’s totally absurd and never lets us forget this: Even in the midst and aftermath of the nuclear strike we get jokes about Malachi’s son “hugging metal God” and Bender searching for survivors in the adult movie theater. At the same time, Bender’s horror at the Shrimpkins’ fates is never turned into a joke, and his guilt over their death is genuine. Bender really is crushed, and the show wisely chooses not to undercut his reaction. The show manages to draw a surprising amount of emotion out of the deaths of characters we met about ten minutes ago.

I’ll skip away for a moment to get to the “B” story: Fry and Leela, who were on the ship when it was attacked, are traveling the world trying to figure out a way to find Bender. Their search leads them to a monastery in the midst of the Himalayan mountains, run by monks who spend their lives using the world’s most advanced telescope to search for the physical embodiment of God living among the stars, where they will send him a message. The show takes the opportunity to make some good jokes (I particularly liked the bored acolyte randomly swinging the telescope around going “No…no…I found hi -! – never mind, no…”). Fry and Leela lock the monks in the monastery’s laundry room and commandeer the telescope for three days straight to search for Bender.

Bender, God. God, Bender. You kids have fun.

We’ll skip back to Bender now, and move onto yet another all-time classic scene in an already stellar episode: Bender, drifting through space, comes face to face with God Himself, or at least a physical manifestation of God in some form. Bender and God have a brilliant conversation about the responsibilities of God to man and man to God, and what it means to answer prayers. When Bender tells God of his experience with the Shrimpkins, God replies that His interactions with those who pray to Him tended to end in very similar ways. God claims he needs to use a “light touch”, like in “safe-cracking, or pickpocketing, or a guy who burns down his bar for insurance money, if you make it look like an electrical thing.” He famously tells Bender “When you do things right, people won’t be sure you’ve done anything at all.”

This is a remarkable scene, made all the more so when you realize that showrunner Matt Groening is a known atheist. He is giving, in effect, an apologetic for why the answers to God’s prayers don’t always appear obvious – and not only that, it’s a really good one. God has a responsibility to help people, but at the same time if people become dependent on God it leads to more problems than it solves. It requires a “light touch”.

As it turns out, prayers get answered after all. God hears one last cry from Fry about how much he misses Bender, and uses this to pinpoint the direction of earth. Bender is sent hurtling back, landing directly next to Fry and Leela in the Himalayas (prompting Leela to point out that “This is, by a wide margin, the most unlikely thing that has ever happened”). Bender manages to get in that “First he was God, and then he met God” before Fry and Leela put a damper on things when they realize they accidentally left the monks locked in the laundry room. Fry figures that their God will surely help them, but Bender rejects this – “Fat chance! You can’t count on God for jack! He pretty much told me so Himself. Now, come on. If we don’t free those monks, no one will.”

This leads into the final punchline, as we zoom out back to God in space, who gives a chuckle and reminds us that “When you do things right, people won’t be sure you’ve done anything at all.”

The psychic was actually pretty helpful too

When I originally watched this episode, I was annoyed at an early gag where Fry asks a (multi-religious) Priest for help, but Fry rejects his offer of prayer, asking if the Priest can do something useful. Of course, the Priest says no. Originally, I thought this was a needlessly mean jab at religious folks who, after all, are actually offering their help to people. In retrospect, the scene gains new brilliance when you realize that Fry essentially DOES pray to God for Bender’s safe return…and his prayer is answered, directly by God, no less. Fry’s love for his friend and faith that what he’s doing will somehow be worth it end up being the crucial factor in Bender’s rescue. In twenty minutes the show manages to deconstruct and then reconstruct the concept of prayer and even God in general.

“Godfellas” was written in season three, when “Futurama” was at the height of its powers. It’s a brilliant example of how to tackle a serious and ambitious subject while straddling the line between funny and poignant, getting across its worldview while making sure to not to sacrifice its story.

If you want to point to an episode to make the case that prime “Futurama” was one of the funniest, smartest, and most superversive shows on television you can do worse than pick “Godfellas”. While I wouldn’t necessarily recommend it as an opening episode for the new fan (maybe “A Prisoner of Benda”, actually, which is ironic considering it’s from the generally, though not always, inferior Comedy Central era of the show), I think every long time fan of the show will agree that it’s one of the finest episodes of one of the finest shows ever made.

Nah, it was just plain subversive. Lot of good math and general nerd jokes though. And select episodes are ok to pull up and watch now and again for me as an adult. But I would never show it to anyone under about 25.

Subtle corruption is perhaps the most dangerous and Futurama was much worse in this regard than, say, the Simpsons, which used such broad strokes that it’s safer in some ways for younger folks to watch if one really wants to give them an example of 90s or early 2000s pop culture.

-

That’s hardly convincing. It was certainly often satirical, but there was a genuine sense of wonder and even optimism that makes it far from subversive. “Godfellas” isn’t even close to that, for reasons I argue hard for here.

-

Also, being inappropriate for kids isn’t equal to subversive (but 25 seems kind of high).

-

Although, I will concede that “Futurama’s” premise was broad enough that it could switch effectively from being subversive sometimes and superversive other times.

Though I still don’t think satire is necessarily subversive. Both Tolkien and Lewis used satire quite effectively in their books.

-

I am a mother of young children (all under 10 and most under 6). My views about how cartoons can operate on very young, unformed minds are not the same as those of people who have the luxury of not using tv as part of the child management toolkit or who don’t have kids.

I purchased the entire series before it was revived and discovered many new episodes I’d missed catching it on Fox originally. Then I had kids old enough to watch tv and it was simply impossible to take the chance when it was so easy to avoid accidental viewing.

This is one of those topics I wish I got enough sleep to discuss at greater length because part of subversiveness is being corrupting and from what I’ve seen, it’s full of potential risk for even teenagers and young adults. Oh well! Only Bender’s Big Score is interesting of the new stuff, I pretend the rest doesn’t exist.

-

Somehow I never saw this episode. I’ve got to remember to check it out later!

My kids love that show. There are a few episodes in every season that they can’t watch for obvious reasons, but overall it’s been a positive experience for my family. It’s definitely one that you have to watch with them, though. We’ve used it as a springboard for conversations about everything from history (The Hall of President’s Heads) to science (pausing to show them that the formulas on the blackboards are legit mathematical constructs) to relationships (Bender might be the most Red Pill character ever shown on TV).