SUPERVERSIVE: Pan, Stone Henge, and the Gods of the Copybook Headings

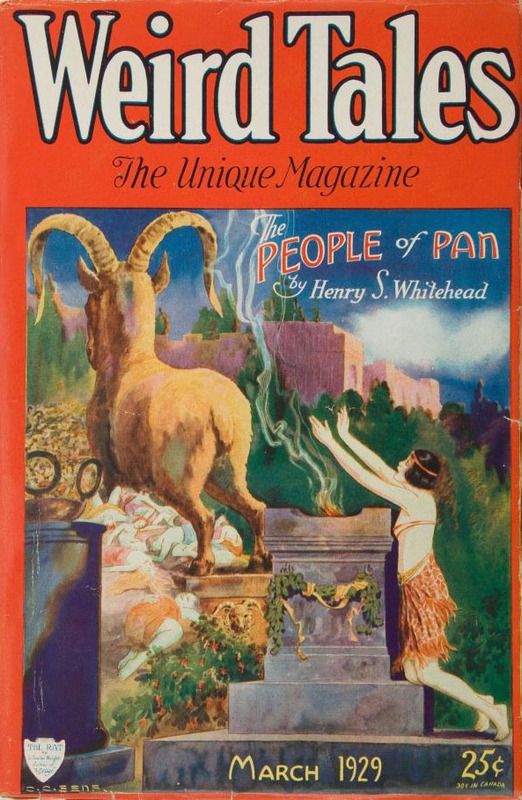

Tuesday , 9, August 2016 Appendix N, Superversive 7 Comments In reading through Appendix N, one of the things that most struck me was how Pan has all but dropped from the literary conversation over time. In Lord Dunsany’s day, that third tier Greek god was something of a rock star. He was so captivating, he was even fundamental to one of the era’s most popular children’s stories. In Dunsany’s tales, he was routinely declared dead, but in the final cadence of the story he’d be up and at ’em again, chasing giggling damsels as if his fate were never in question.

In reading through Appendix N, one of the things that most struck me was how Pan has all but dropped from the literary conversation over time. In Lord Dunsany’s day, that third tier Greek god was something of a rock star. He was so captivating, he was even fundamental to one of the era’s most popular children’s stories. In Dunsany’s tales, he was routinely declared dead, but in the final cadence of the story he’d be up and at ’em again, chasing giggling damsels as if his fate were never in question.

A few decades later it’s different story. In C. L. Moore and Poul Anderson’s take, he is still treated as the central figure of classical myth, but he really is depicted as being on his way out. It’s the advent of Christianity and the burning of the sacred groves that are the end of him. Though he might put in the occasional cameo on some distant isle or Fairyland, he is far from the jollical fellow he once was. He’s downright morose about the passing of the elder days.

A generation or two after the pulp era even this sort of thing drops off, however. I’ve wondered if this was maybe a consequence Tolkien’s displacement of Lord Dunsany as being the guy that is synonymous with the fantasy genre. Dunsany’s lapse into obscurity would necessarily change the conversation in and around fantasy, after all. Misha Burnett’s has a different conjecture on what might underlie the trend, however:

In my opinion Pan became obscure because that which Pan symbolizes went from being a cautionary tale to being an ideal.

Prior to the middle of the 20th Century it was self-evident that lack of self-control leads inevitably to privation at the least, if not outright famine.

Like Aesop’s grasshopper, Pan was the spirit of indolence and dissolution–sex, drugs and rock’n’roll. The potential for violence was certainly evident as an undercurrent, but the real power of the image to terrify was that those under Pan’s influence live for the moment. They don’t plant, they don’t harvest, they don’t plan for the winter.

The unprecedented affluence of post-WWII America allowed a significant portion of the population to escape the consequences of idleness. Of course the hippie generation ceased to fear Pan as a devil, they worshiped him as a God.

So Pan’s mythic potency was tied directly to the fact that pretty well everyone grasped the fact that actually following his lead en masse would be cultural suicide. The fun of flirting with him was part and parcel to the understanding that he is in fact dangerous. Take that away and he’s just another forgettable fantasy hybrid.

You see the same transition in depictions of Stone Henge and druids. In A. Merritt’s Creep Shadow!, for instance, the idea is that these people did such horrible, unthinkably ghastly acts that could very well have triggered the end of the world. Dunsany, too, takes it for granted that whoever was behind Stone Henge was up to no good. The subtext here is that it’s a good thing that only the stones remain: the Gods of the copybook headings surely came down and saw to it that we have basically no idea what they were actually up to. At about the same point that Pan drops out of the discussion, a new frame emerges: the druids were merely harmless, nature-loving astronomers that maybe talked to aliens occasionally.

If we don’t actually know much about who the druids were or what Stone Henge is really for, then I guess maybe that’s as reasonable of a theory as anything. It is, however, one that’s short on either thrill or charm. At first it might appear that myth is merely a function of culture, but I don’t think that’s quite all that’s going on here. These new stories are not adaptations or evolutions of the old. They have an entirely different function altogether.

I just can’t read about Stonehenge without thinking of Spinal Tap: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qAXzzHM8zLw

But more seriously, that is an interesting and troubling thought – that Pan has waned in use because he no longer symbolizes spiritual danger and vice. You bring up Tolkien here, and it reminds me of the conversation about “Tolkien elves” and the sense of danger and otherworldliness having fallen to the wayside.

“Pan was the spirit of indolence and dissolution–sex, drugs and rock’n’roll.”

The Pan in Tom Robbins Jitterbug Perfume might be last breath of the archetype.

Of course all his Novels can accurately be described as the last breath of all hippy archetypes.

“takes it for granted that whoever was behind Stone Henge was up to no good.”

Caeser tells us that the Celts would stuff a bunch of people in giant wooden statues and set them on fire for sacrifice.

Dunsany probably read that. While contemporary authors have not.

-

“Caesar tells us that the Celts would stuff a bunch of people in giant wooden statues and set them on fire for sacrifice.

Dunsany probably read that. While contemporary authors have not.”

I guess I should elaborate on this rather then be a pontificating sperg which I often am in these comments. (sorry about that. I am working on it)

A. Merritt and Dunsany grew up at a time when Latin was still being taught to school children. According to wikipedia Caeser’s Commentaries on the Gallic War was “often lauded for its polished, clear Latin. This book is traditionally the first authentic text assigned to students of Latin, as Xenophon’s Anabasis is for students of Ancient Greek”

In “The Gallic War” Caesar is unkind in his descriptions of the Gauls (Celts) they are dishonourable, craven and as I mentioned above engaged in human sacrifice.

This is why I think writers like A. Merritt and Dunsany take “for granted that whoever was behind Stone Henge was up to no good.”

Because as children they were told in their Latin studies by the horrible pagan dictator Caesar that the Celts were even worse them him.

And not only did they take for granted that the Celts were up to no good but pretty much every English speaking educated person alive did.

Or at least this is what I think and the reason why I think it.

Note: The Celts were probably up to no good. This is not a defence of them just a hypothesis of how and why they were perceived back in the day.