Swords of Steel, Volume 2: The Lost City of Tehm

Friday , 31, March 2017 Short Fiction, Uncategorized 8 Comments Morgan reviewed the first volume of Swords of Steel back in February of this year. The second volume was released in 2016, and it provides an excellent chance to analyze each of the twelve stories as part of Castalia House’s on-going effort to review the wealth of short fiction being produced by small and independent publishers. As with volume one, the marketing hook for the Swords of Steel series is that the contents were written by heavy metal musicians. So if you’re too old or too square, then this book offers a chance at the passion, the history, and the glimpses into deeper, darker secrets of life and death, but in the far more sedate prose form.

Morgan reviewed the first volume of Swords of Steel back in February of this year. The second volume was released in 2016, and it provides an excellent chance to analyze each of the twelve stories as part of Castalia House’s on-going effort to review the wealth of short fiction being produced by small and independent publishers. As with volume one, the marketing hook for the Swords of Steel series is that the contents were written by heavy metal musicians. So if you’re too old or too square, then this book offers a chance at the passion, the history, and the glimpses into deeper, darker secrets of life and death, but in the far more sedate prose form.

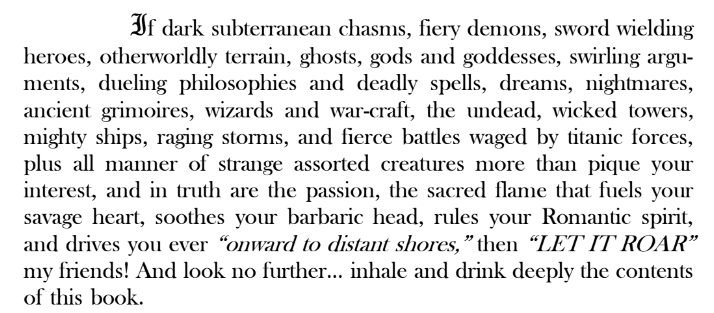

The opening sentence of Swords of Steel, Volume 2, hits the reader with a power chord of a hook:

David DeFeis knows how to write a pulse-pounding introduction. He leaves the reader eager to turn the page, to get to the good stuff~

Moments later the first tale, The Forgotten City of Tehm, by Ernest Cunningham Hellwell, begins with a rip-snorting, high-octane…lengthy geography lesson?

Well, that’s not a good sign. It’s only after two pages of geography and history and political background that the reader – if he has persevered – reaches the first inklings of a story. The tale proper begins with a visit by three western mercenaries to the court of the local potentate, Haru Pesch. Having brought one of his caravans to his palace in Rho Thule, the ruler now entrusts them with a mission to guard the caravan’s return to the great city of Khotar, this time carrying goods of even greater value. With the preliminary negotiations out of the way, we finally get to the adventure of the three mercenaries, right? Not so fast. We also get to spend an evening in a local tavern, where the three meet a famous lost prince of the west turned gladiator turned mercenary, named Tarsus.

The next day, they finally set out on the trail to guard the caravan. The story is eleven pages old at this point, and we haven’t yet had our first intimation of danger. That’s inexcusable for a tale of blood and thunder. How much more effective would this story have been if it opened with the raiders leaping up from their disguised pits in the very center of the caravan’s defensive circle, just as the main force of mounted bandits hit the line of defenders? When the western men don’t break because they know how to conduct a fighting retreat, that’s when you reveal their background. When the blonde barbarian comes riding over the hill to drag the three Comorians to safety, the reader should be left wondering, “Who the heck is this guy?” That sort of subtle and short lived mystery engages the reader’s brain and keeps them turning pages.

It gets worse, but it also gets a lot better. Before we delve into more of the story’s weaknesses, let’s look at Hellwell’s strengths.

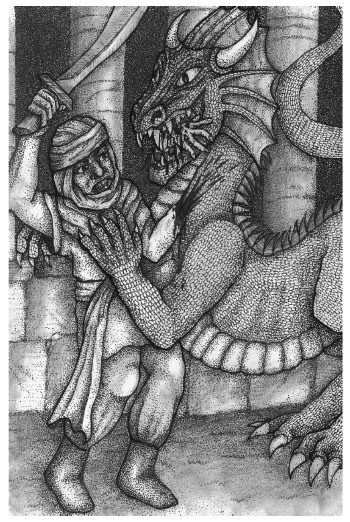

Spoiler Illustration by Eva Flora Glackman-Bapst

Hellwell writes with an undeniable courage, ignoring the societal norms that have sprung up over the decades to great affect. He unabashedly uses the shifting sands and lawlessness of the pseudo-middle-east to lend The Lost City of Tehm an exotic flavor. One simply doesn’t do such things these days when all are one and everything is the same and one mustn’t write for a western audience, but only for a vague and nebulous “everybody”. It’s a small rebellion – this nod to his audience and admission that Swords of Steel isn’t for everyone – but it’s the sort of rebellion that could only survive outside of the established publishing world. This is clearly a group that writes for themselves, and not the approval of distant, effete urban publishers.

Hellwell has a gift for names. Names are powerful things, and when used correctly, they evoke a deep sense of history and meaning. They tie civilizations together and allow for maximum meaning with minimal exposition. The three adventurers who begin our tale are named Braxus, Arrak, and Tarrak. They work for Haru Pesch, ally of Almec Kahn, against the schemes of Khotar of Khijar. With only those names, and none of the preceding eleven pages of introduction, we can already infer that the three men are strangers in a strange land. We do not need to know that they are ex-legionaries of Arcania and Comoria until we need to know that, which should happen just about the time the mercenaries work as a unit against the howling red-sashed bandits. When the lost prince rides to their rescue in the midst of the disastrous raid on the caravan, we can guess that Tarsus is a westerner just by his name.

Hellwell writes from a position of strength and security. Consider the lost prince’s motivation, which one would be hard pressed to find in the sort of pink-slime fiction being peddled at the local brick and mortar store:

That’s the money shot, right there. That’s an introduction. Those two short sentences tell you everything you need to know about Tarsus. We’ve seen the strength of his arms already, now we see the strength of his character. He is a lonely man, but honorable, and loyal even to a stranger who would buy him a drink in a tavern out of comradely affection.

Affection? There’s a word you don’t see bandied about much these days when it comes to male relationships. The forces that control culture have no experience or understanding of what healthy male relationships look like. Normal bonds of brotherhood, the timeless recognition that competent men have for each other, and the unbreakable bonds forged by men who win through adversity together are no longer an acceptable part of mainstream discourse. The language and emotion of the giants of science fiction and fantasy was replaced when the noodle-armed poindexters of the 50s and 60s managed to connive their way like a horse of Wormtongues into positions as leading critics and editors of the genre. The resultant wholesale repudiation of strength and courage and fraternity by the authors of the last half of the twentieth century has drained fiction of a powerful source of conflict and motivation. Into this bland and gray wasteland of meaningless writing strides Hellwell with a plain spoken honesty that resonates with power all out of proportion to word count.

“You called me a brother in arms. I had forgotten that I had any.”

With those two sentences, Hellwell says more about the timeless experiences of men of action than most writers can say in a full length novel. And it’s this fearlessness and ability to convey so much in so few words that makes Hellwell’s shortcomings as an author all the more frustrating. Perhaps Hellwell is new to the game, and just needs more time to find his voice. The prose is uneven with clunky passages rubbing elbows with flashes of brilliance. Perhaps he just needs a better class of editor. This is a self-published work, after all. Perhaps he needs to read a few more “How to Write X” essays. This reads like a love story to the classic works, but written by a writer trying to find his own way through the well-trod wilds of fiction writing.

At this point a few examples are worth reading, not so much to criticize as to illustrate:

- “The Khoshite landed gracefully like a cat upon the floor of the lower level.” Yes, cats land gracefully, the use of the adverb followed by the descriptor is redundant. This is the sort of clumsy phraseology that your reader might not notice, but their ear does. Enough passages like this and ‘your reader’ will become ‘somebody else’s reader’ before they finish your tale.

- “Argus realized he was looking at the same man that had been standing in the cart at the caravan watching them ride away.” Subject and clause matters. Commas matter. Long sentences matter. (This is actually the second part of an even longer sentence!) After a bit of thought, Hellwell seems to be trying to convey, “Argus recognized the man as the muscular Khoshite who had stood like a rock amidst the frenzy of pillage as the bandits ransacked the caravan. The man had stared from the bed of a broken cart, and placidly watched as Argus and his companions abandoned their charges to the rapacious tribesmen.”

- “For three more days the caravan traveled with no incident with twenty-five foot soldiers and fifteen mounted cavalry keeping watchful eye for raiding bandits.” It’s good that they had no incident with soldiers and cavalry who were watching for – oh, the foot soldiers and cavalry were on their side. Here’s another strong candidate for tight editing. No incident is one idea. The guards is another. That requires two sentences or better connective tissue, and given that this sentence occurs four days into the journey, it’s probably too late to mention the guards. We’ve glossed over the journey so far but adding 35 more men to the roster now requires the reader to rewind his mental tape and re-imagine the journey, but now with extra outriders and spear catchers.

For authors, these are the sorts of small mistakes that hold back a potentially great work. For attentive readers, these are the sorts of passages that can help you recognize early on whether a work is worth pursuing to the bitter end or not.

Unfortunately for The Lost City of Tehm, it’s not worth the pursuit. Hellwell shows a considerable amount of potential, and one hopes he will pursue his craft, because with a voice of his own and some tighter editing, this could have been a story to remember. As it stands, it’s not a story best enjoyed as a case study in how not to do it.

Jon, you should throw in a link with the review so people can impulse buy it.

I really dig this passage, Jon:

“The forces that control culture have no experience or understanding of what healthy male relationships look like. Normal bonds of brotherhood, the timeless recognition that competent men have for each other, and the unbreakable bonds forged by men who win through adversity together are no longer an acceptable part of mainstream discourse. The language and emotion of the giants of science fiction and fantasy was replaced when the noodle-armed poindexters of the 50s and 60s managed to connive their way like a horse of Wormtongues into positions as leading critics and editors of the genre. The resultant wholesale repudiation of strength and courage and fraternity by the authors of the last half of the twentieth century has drained fiction of a powerful source of conflict and motivation.”

The Left must poison every well, after all.

-

Critics’ constant description of deep friendships between men (or even between women, for that matter) as “homoerotic” is really sad.

-

There is that famous line from “How Harry met Sally” about how men and women can never stay good friends… I am thinking of that, but applied to men too ie perception of male friendship.

Nowadays, you cannot present close male friendship without people projecting homosexuality into it. And they are projecting it backwards too, be it on the hobbits in LotR or to knights in a medieval romance.But that is just one aspect of it. Idea of male camaraderie has been poisoned in so many ways, in our modern pop culture.

Hellwell’s story in the first volume was more of a weird horror with a gothic flair that was easily one of the best in that book. I don’t know how much prose fantasy he’s written, and it could be that he’s simply weaker in that area.

But damn if he doesn’t play some monstrously heavy prog-rock!

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J8hk7c-ZQQk&w=560&h=315%5D

-

Yeah, Manilla Road are native Kansans like myself. An ex-con handed me a tape of theirs back in ’89. They played in Wichita last January but I wasn’t able to make it.

Thanks for taking the time to write such a detailed analysis, even though it was not 100% complementary. An honest, in-depth critique is better than some reviews I’ve seen where it was clear they didn’t even read the book. I’ll pass this along to Hellwell, and I hope you find the other stories in Swords of Steel more to your liking.