The Atomic Age Narrative: Galactic Empires

Sunday , 9, April 2017 Fiction, Short Fiction, Uncategorized 13 Comments“Campbell saw man as a tool-making animal.”-Brian W. Aldiss

Brian W. Aldiss (born 1925) edited some of my favorite science fiction anthologies. I have read a little bit of Aldiss’ fiction but not much. I do respect the guy because he was in the British Army in Burma in World War 2 in Gen. William’s Slim’s “Forgotten Army.” That Anglo-Indian Army inflicted the biggest land defeat on the Imperial Japanese Army at the Battle of Imphal and Kohima in WW2.

Brian W. Aldiss (born 1925) edited some of my favorite science fiction anthologies. I have read a little bit of Aldiss’ fiction but not much. I do respect the guy because he was in the British Army in Burma in World War 2 in Gen. William’s Slim’s “Forgotten Army.” That Anglo-Indian Army inflicted the biggest land defeat on the Imperial Japanese Army at the Battle of Imphal and Kohima in WW2.

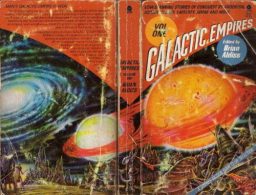

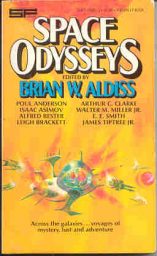

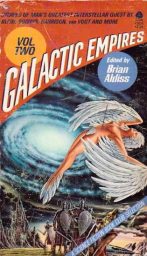

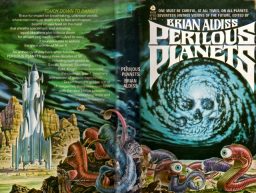

Aldiss emerged as a writer in the 1950s, part of the same generation as E. C. Tubb and Kenneth Bulmer. In the 1970s, he edited some anthologies that were against the grain of the times: Space Odysseys (1974), Space Opera (1974), Evil Earths (1975), Galactic Empires (1976), and Perilous Planets (1978).

This was the time of “inner space” and novels such as Ursula Le Guin The Dispossessed winning the Hugo Award. Yet, there was some push back, Galaxy magazine was publishing David Drake’s “Hammer’s Slammers” and Fred Saberhagen’s “Berserker” series.

Leigh Brackett’s Best of Planet Stories died after one volume. Brian W. Aldiss edited a series of unabashedly nostalgic anthologies that were pulp heavy in content.

His introduction to Galactic Empires Volume One is one of the greatest introductions to an anthology I have ever read. He has some great lines:

“Galactic empires represent the ultimate absurdity in science fiction.

Galactic empires represent a promiscuous liaison between Science and Glamour, with Glamour generally in the ascendant.

Galactic empires represent the spectaculars of the sf field.

As such, galactic empires have often been condemned by the serious-minded. That may be less because of faults intrinsic in the genre than because the serious-minded are practiced in condemnation. ”

“What the authors do in the main is tell us a story adorned with alien creatures, swordplay, fascinating gadgets, and–for preference–beautiful princesses. The story itself is generally fairly traditional, the crux being resolved by quick wits, courage, and brute strength. If this

sounds like the recipe for a fairy-tale, the point about fairy-tales is that they enchant us and enlarge us and enlarge our perceptions. . . Science is thin stuff beside this legendary material.”

“You have to love the way villains or heroes flee across the remote star galaxies in pursuit of each other. You have to love the way Elder Races, Hideous Secrets, Ancient Forces or plain sneaky teleporters crop up at every turn. And you have to love the Imperial women.”

“C. S. Lewis–in general an astute critic of sf–brought another objection against the galactic story, when he complained that the author ‘then proceeds to develop an ordinary love-story, spy-story, wreck-story, or crime-story.’. .Lewis misses the point. We read the love-story, the spy-story, or whatever because it takes place on a fifty-kilometer-long spaceship, because it is set on a planet where the sun goes into eclipse every hour on the hour, because it happens in the capital city of the greatest empire the universe has ever known. Our sensibilities are affected by these settings, and by the knowledge that we are reading about legendary characters living hundreds of years in our future. We would toss the story aside unread if it all took place in Leicester in 1976.”

Aldiss quotes Lewis asking Tolkien:

“What class of men would you expect to be most preoccupied with, and most hostile to, the idea of escape?” Tolkien replied ‘jailers’.”

The contents especially of Galactic Empires volumes one and two are sublime. Aldiss has this zinger of a comment about the run of the mill anthology:

“There are many sf anthologies on the market, few of their editors appear to have studied anything but other anthologies. I am interested in rescuing from oblivion stories, not necessarily by famous authors, which–for one reason or another–can be read and enjoyed today.”

The two volumes contain 21 stories, seven from Astounding Science Fiction, four from Galaxy, and most importantly four from Planet Stories. The stories appeared from 1942 to 1975 with 17 of the stories from the early 1950s.

You have future Pulitzer Award winner Michael Shaara’s first story with Asimov’s first Foundation story, juxtaposed with one of Poul Anderson’s Terran Empire stories.

Volume 2 contains rip-roaring adventures by John D. MacDonald (from Super Science Stories), Gardner F. Fox and Poul Anderson from Planet Stories.

I first read Galactic Empires volumes one and two 29 years ago. I picked up the hardbacks at a used bookstore (Mac’s Back Paperbacks in Cleveland Heights, OH) and read the stories. I especially liked the Planet Stories reprints, but turned the books back in for credit. Years later, I picked up the Avon paperbacks used.

I could quibble that Astounding Science Fiction from the early 1950s is over represented. I also realize that Aldiss was picking stories to fit the subsections of the two books as part of the narrative rise, peak, and decline of the galactic empire.

Space Odysseys and Space Opera are also great anthologies. If anything, they are even more widely focused in contents. I did not even know about Perilous Planets until this week when researching Aldiss’ anthologies.

Aldiss has this (to me) strange comment in the introduction to Galactic Empires Volume Two:

“The galactic empire is a sort of crystallization of space opera; there are others, of which Sword-and-Sorcery is one.”

One could say the space opera is the next logical step after the planetary romance/sword and planet story. Sword and sorcery fiction does have a little bit of literary DNA from sword and planet but for the most part is the collision of the historical adventure with cosmic horror. Aldiss appears to be retrofitting “space opera” backwards to include sword and planet.

.Aldiss wrote a history of science fiction called first The Billion Year Spree and then the later revised and expanded Trillion Year Spree. Howard gets a very cursory mention on page 173 with:

“Robert E. Howard (1906-1936) created a brawny bone-headed hero called Conan, whose barbarian antics are set in the imaginary Hyborian Age, back in pre-history when almost all woman (sic) and no clauses were subordinate.”

Aldiss dismisses Howard but at the same time waxes eloquently about Leigh Brackett:

“Leigh Brackett had many successes, among them The Sword of Rhiannon (1953), before becoming a high paid script writer in Hollywood. Rhiannon is the most magical sub-Burroughs of them all, the best evocation of that fantasy Mars we would all give our sword arm to visit.”

Aldiss misses the point that Brackett acknowledged her debt to Robert E. Howard and that she was working the same area as Howard. This is again a case of cursing those who look in the past for inspiration while praising those who put the past into the future. Gardner Fox, Poul Anderson, Leigh Brackett incorporated Robert E. Howard’s sparkle and color into their space opera which had been drab under the hand of Isaac Asimov.

Science fiction right now appears to be backward looking considering how “steam punk” and the newer “diesel punk” sub-genres are popular.

If you see these anthologies, pick them up. Unfortunately, Avon paperbacks from that era have a habit of spine cracking. I would love to see the Galactic Empires volumes combined as a Barnes & Noble bargain hardback with the Avon paperback covers used. That was a wrap around by Alex Ebel.

Something that I noticed when going through the various editions of these anthologies, four out of five were reprinted as paperbacks after the success of Star Wars. That movie gave a brief shot in the arm to space opera in the late 1970s before the big change of the 1980s. These books are a celebration of adventure science fiction.

There is plenty of classic space opera waiting to be reprinted. A book filled with blood and thunder could be filled with Poul Anderson, Gardner Fox, Alfred Coppell’s “The Magellanics,” John Brunner’s “The Wanton of Argus,” one of H. Beam Piper’s “Empire” stories, Tom Godwin etc. Considering how Disney is cranking out a Star Wars movie a year, it is time to introduce the kiddies to the source material.

“brawny bone-headed hero called Conan”

Why is it that, whenever one encounters comment about Conan and REH from this period, it reads as if that person never read Conan (or, at best, have only read comments and pastiches written by de Camp et al).

“Why is it that, whenever one encounters comment about Conan and REH from this period, it reads as if that person never read Conan (or, at best, have only read comments and pastiches written by de Camp et al).”

I assume that’s rhetorical?

Aldiss is alright. I’ve read few of his anthologies in the past, and man’s got great and incredibly broad taste. One anthology of his was my introduction to writers like Lernet-Holenia and Collier, for example.

I am less enamoured with his writing tho. I appreciate Hothouse for how all out bonkers it is, but it was incredibly tedious and slow read for me in spite of its short length. And, even though I can imagine that he was going for some sort of scientifically believable Dying Earth premise, his setup ended up being harder to swallow than those that made no such considerations.

Aldiss should’ve stuck to anthologies. His Helliconia books are pretty tedious and he seems to have stolen the life-cycle he sticks in there from John Morressey’s more enjoyable FROSTFIRE AND DREAMFLOWER. Aldiss also talked trash on May’s Pliocene Saga, a pulpy science-fantasy adventure that will be read long after anything written by him.

I find it curious that it was against Aldiss that Moorcock and the British New Wave were rebelling.

-

Moorcock was going to “rebel” no matter what. I imagine that Aldiss didn’t talk trash on the UK and the British Empire long and loudly enough.

-

Going by some of these quotes, he appears to be far removed from Moorcock in certain ways. Moorcock was very much in “antidote to escapism” mode early one, whereas this guy celebrates escapism. He also liked quite a few of those “passe” pulp tropes and authors, by the looks of it. Respected Tolkien and Lewis, too.

And where he disagrees with Lewis, is where people like Jeffro would disagree:

“C. S. Lewis–in general an astute critic of sf–brought another objection against the galactic story, when he complained that the author ‘then proceeds to develop an ordinary love-story, spy-story, wreck-story, or crime-story.’. Lewis misses the point. We read the love-story, the spy-story, or whatever because it takes place on a fifty-kilometer-long spaceship, because it is set on a planet where the sun goes into eclipse every hour on the hour, because it happens in the capital city of the greatest empire the universe has ever known. Our sensibilities are affected by these settings, and by the knowledge that we are reading about legendary characters living hundreds of years in our future. We would toss the story aside unread if it all took place in Leicester in 1976.”

Galactic Empires was a staple in the mid-1970s SFBC offerings so there are plenty of book club editions about.

I read it then and second the recommendation. Some very memorable stories.

I gotta stop coming here. Every time I do, I am introduced to some really cool writer I should have been reading already (in this case Saberhagen), thus I add to the have to steal time to read pile. Too much to read is the best problem to have.

Aldiss wrote a good couple of coming-of-age stories set in primordial societies in Hothouse and Non-stop. Exotic and violent travelogues with deft worldbuilding – they stand up well. I rate him more than Clarke for British SF of that era.

The short fiction I’ve read hasn’t been as good.