The Atomic Age Narrative: Half-Baked Posthumous Psychoanalysis

Sunday , 12, March 2017 Uncategorized 11 Comments

The Gruesome Twosome: L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter

L. Sprague de Camp (1907-2000) was another writer who went from writing fiction to book reviews, non-fiction articles and books, and biographies. If you look at his bibliography, non-fiction essays appear to outnumber the number of fictional stories he wrote.

De Camp was part of the Campbellian revolution in the pages of Astounding Stories/Science Fiction in the late 1930s. He was a major writer for that magazine. L. Sprague de Camp was probably THE quintessential writer for Unknown/Unknown Worlds. His fiction had a light-hearted tone, generally erudite but lacking in pathos and gravitas. He did not seem to take his own stories too seriously. De Camp also had a life-long habit of starting series that were strong at the beginning but lost steam and petered out.

He spent some time in the U.S. Navy during WWII at the Philadelphia Shipyard doing engineer work on mundane things (He had a degree in Aeronautical Engineering). If not a man with screwdriver, he was an engineer with a slide rule. During that time, he stopped writing science fiction and fantasy. His return to fiction in the late 1940s seemed to take some time. It was not until 1949 that he was back to his pre-war production levels with the Viagens series.

De Camp discovered sword and sorcery fiction when Fletcher Pratt passed on a copy of the Gnome Press edition of Conan the Conqueror (“The Hour of the Dragon”). He was intrigued about this previously to him unknown genre.

Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories inspired him to write his own series of prehistoric fantasy within what he called “The Pusad Age.” The Tritonian  Ring is from this period. He came up with a great fantasy setting. In fact, the setting is better than the stories that he produced set within it.

Ring is from this period. He came up with a great fantasy setting. In fact, the setting is better than the stories that he produced set within it.

At the same time, de Camp was writing book reviews for science fiction magazines. He reviewed Conan the Conqueror in Astounding Science Fiction, April 1951 issue. He reviewed J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring for Science Fiction Quarterly, August 1955 issue.

De Camp was attracted to heroic fantasy/sword and sorcery. He also had to backhand some of the authors. It is a strange relationship. He seemed to have to throw in some mocking and negative criticism to keep his street cred with the science fiction crowd. He also had a bad habit for indulging into posthumous psychoanalysis.

His review of Conan the Conqueror for example:

“Howard was an almost-very-good writer who might have overcome certain limiting quirks had he not killed himself at an early age…His main fault was a tendency carelessly to throw his imaginary world together anyhow, so that the poor carpentry shows.”

In his review of Conan the Barbarian (Gnome Press, 1954) in the August 1955 issue of Science Fiction Quarterly, he refers to Robert E. Howard as “kind of bush-league Eddison.”

De Camp’s introduction to King Conan (Gnome Press 1953) includes the tale of de Camp going over to Oscar J. Friend’s apartment and meeting Harold Preece:

“Preece told me how frustrating Howard had found life in Cross Plains, Texas; how he could never get very far away because he supported his parents by his writing and because his mother had kept him too closely tied to her apron-strings. This excessively close relationship proved fatal to Howard…Preece echoed my own thoughts: ‘If he’d only gotten away…If he’d only gone out with girls the way the other boys did.’” De Camp also included the line: “And, without doubt, Howard was a psychological case-study…Howard suffered from delusions of persecution, and his end constituted a classic case of Oedipus complex.”

De Camp included this line in The Science Fiction Handbook in 1953 also. So right off, de Camp is figuratively peeing in the swimming pool.

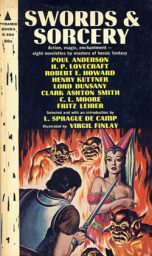

In 1963 with Swords & Sorcery, the first of the sword and sorcery fiction anthologies include the line “Although a big, powerful man like his heroes, he suffered delusions of persecution and killed himself in an excess of emotion over his aged mother’s death.” He did the same thing with the introduction to the H. P. Lovecraft story (”The Doom That Came to Sarnath.):

“He dwelt with two aged aunts, seldom ventured abroad save at night, and indulged in many obsessions and affectations.”

The other dead writer, Lord Dunsany, on the other hand is described as “the kind of lord than many people would like to be if they had the chance. He was 6′4″ tall, and a sportsman, soldier, traveler, and a man of letters, with a grand gift of poetic speech.”

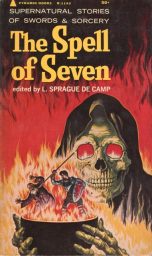

The Spell of Seven in 1965 repeats the formula. It is here the infamous “Maladjusted to the point of psychosis” line is trotted out. That line was reused in 1967 with Conan (Lancer, 1967). I am in the medical field and a comment of this nature is called “editorializing.” If you were to say this about someone living, you would probably get sued. My Legal Encyclopedia and Dictionary describes libel as: “Any malicious defamation expressed in printing or writing and intended to blacken the memory of one who is dead or the reputation of one who is living and expose him to public hatred, contempt, or ridicule is a libel.” A good attorney could probably make a case of libel in this instance.

Conan also included the oft repeated line by de Camp:

“His personality was introverted, unconventional, moody, and hot-tempered given to emotional extremes and violent likes and dislikes.”

An essay entitled “Conan’s Ghost” (The Conan Grimoire, Mirage Press, 1968) recycles introverted personality line, and also an inadvertantly funny  line from Alan Nourse, M.D.:

line from Alan Nourse, M.D.:

“That sleep-walking alone indicates a profoundly neurotic personality–probably hysteric and hyper-suggestible…It’s obvious that here was a fellow who wasn’t wired up just right in the matter of sex.”

“The Miscast Barbarian” (Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers, Arkham House, 1976) is a splicing of “Memories of R.E.H” (Amra, Vol II, #38) and “Skald in the Post Oaks” (Fantastic, Oct. 1972) and recycles previous comments. De Camp paraphrases himself: “It seems obvious that the dominating factor in Howard’s life was his devotion to his mother, which answers to the textbook descriptions of the Oedipus complex.” With incredible hubris de Camp then denies doing what he just did:

”We must bear in mind, however, that posthumous psychoanalysis is at best a jejune form of speculation.” Let us not forget the line– “It is plain he was not a well-balanced human being.”

Dark Valley Destiny (Bluejay Books 1983) does not show anything in the way of growth of understanding of Robert E. Howard by L. Sprague de Camp. You don’t get the “maladjusted to the point of psychosis” line but plenty of lines similar in tone. Here is a montage:

“Robert’s many lapses into phantasy in order to liquidate discomfort.” “Together these elements nurtured the violent phantasies of a youthful writer who never learned to cope with reality.” “Much more real to Robert Howard were the demons and goblins from the depths of hell, the strange and evil creatures from other worlds, and the hate-filled, unregenerate humanity–the larcenous oil men, the prostitutes, and the witches who passed as fellow mortals along the streets of Cross Plains.” “Conversely, girls were not likely to be fascinated by Robert. His repute as the town eccentric, his unconventional views, and his spells of misanthropy and moroseness made him unattractive to the local girls.” “Her son’s pathological dependence on her.”

L. Sprague de Camp was an engineer by education, not a psychologist, not a psychiatrist. The big question is why did he engage continuously in dressing up his writing with faux psychology? Some have attributed sinister motives. Examining de Camp’s writings on other authors, there is a pattern. If the writer was alive, you got a pass. If you were dead, the psychoanalysis would creep in. The more de Camp wrote on a subject, the more psychoanalysis. He engaged in it with the Lovecraft biography. Sunand Tryambak Joshi wrote in his H.P. Lovecraft: A Life (Necronomicon Press, 1996):

Sunand Tryambak Joshi

“Whenever de Camp encounters some facet of Lovecraft’s personality that he cannot understand or does not share, he immediately undertakes a kind of half-baked posthumous psychoanalysis. Hence refers to Lovecraft’s sensitivity to place as ‘topomania’–as if no one could be attached to the physical tokens of his birthplace without being considered neurotic…He was out of his depth: and this makes his schoolmasterly chiding of Lovecraft all the more galling…these value judgements were arrived at through inadequate understanding and false perspective.”

You could take out Lovecraft’s name in that passage and insert Howard’s and be correct.

De Camp does it to Henry Kuttner in “Conan’s Compeers”:

“A mature writer, however, assimilates these influences, so that his writings no longer betrays imitation. Kuttner never reached this stage. This fact, together with his lavish use of pen names, suggests a deeply-rooted lack of self-confidence.”

After Lin Carter died, de Camp started the comments about Lin Carter saying he never grew up. In the early nineties, de Camp was even asking the opinion of a psychologist when describing some de Camp non-admirers in REHUPA (Robert E. Howard United Press Association). He then published the doctor’s opinion in one of his letters in one of the mailings.

I think at the end of the day, de Camp used the psychological mumbo-jumbo to give a patina of authority to his opinions. For whatever reason, he could not just give his opinion and leave it at that, he had to dress it up with pseudo-scientific sounding language as a defense mechanism. I would never think of trying to diagnose a condition of someone dead based on subjective comments given to me by other people. Interestingly, Karl Edward Wagner was a Medical Doctor who did his residency in psychiatry. If anyone could have waded into this area, it was him. His forewords and afterwords for the Berkley Conan books have not a word of psycho-babble.

De Camp’s review of Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring is laughable today.

“Professor Tolkien’s central characters (he teaches English at Oxford) are hobbits–a species of pudgy, hairy-footed dwarf that may be described as a cross between an English white-collar worker and a rabbit…I too found Tolkien’s ‘dear, silly old hobbits’ too dreadfully sweet for my drier taste at times.”

Years later, de Camp could not resist sniping at Tolkien in Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers for Tolkien’s indulgence of names for the same character in different languages: “Aragorn who is also “Elessar, also Dunadan…All of which seems a bit much.”

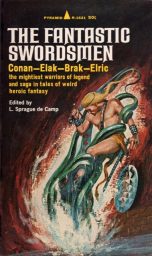

L. Sprague de Camp is a mixed bag. He loved heroic fantasy. He did edit the very first paperback anthology of the genre: Swords & Sorcery (Pyramid Books, 1963) and later books including The Spell of Seven, The Fantastic Swordsmen, and Warlocks and Warriors. These are important anthologies despite some of the odious author introductions. Combining the four books into two or better three mass market paperbacks might help educate some of our younger readers and introduce legacy sword and sorcery fiction to those who have no knowledge of it. De Camp’s attraction to psycho-analysis is a strange thing in of itself, perhaps worthy of psycho-analysis itself!

Spraguey was also a member of the Buds of Hard SF Club. Not surprising, since a couple of his fellow Navy engineers at the shipyard were Heinlein and Asimov. I call this particular Fellowship of the Screwdriver the “Three Enginers”. Somebody should photoshop a pic where all three are standing together, clashing their sliderules above their heads.

https://www.kirkusreviews.com/features/asimov-de-camp-and-heinlein-naval-aviation-experim/

Spraguey made very sure to cover the time dilation effects of near-lightspeed travel along with numerous other items of “hard” punctiliousness. In some ways, he was the the Hardest Bud of the Three Engineers when it came to SF. All three of them fell hook, line and sinker for several dubious postulations of the social “sciences” of the time.

The psychobabble was very much of its time. The popularization of Freudian psychoanalysis in the 1940s — and the “scientific” use of it by advertisers and propagandists — made it seem to a lot of people that the mechanisms of how the mind works had been solved. A lot of 1950s and 1960s SF involved psychological “technology” allowing accurate and reliable prediction or manipulation of human thought.

There’s also the fact that Freudian psychology, for writers of fiction, is a perfect dramatic tool. Consider the “narrative” of every psychoanalytical case-study:

1. A person is troubled, unable to achieve happiness, possibly afflicted by drink, drugs, or sexual problems.

2. The sufferer is counseled and taught by a wise, enlightened person who has secret knowledge (a psych degree).

3. With the aid of this wise counselor, the sufferer strips away illusions, lies, and self-deception to learn truths about himself, and discovers the ancient wound or trauma which is the source of his affliction.

4. Equipped with self-knowledge, the sufferer achieves happiness.

There’s a reason why that remains the bog-standard template for nearly ALL contemporary fiction: it’s an absolutely perfect dramatic structure! Even though Freudian psychoanalysis is a rarity, viewed by most psychiatrists as a quaint relic, it is still THE model for all “character arcs” in modern fiction. That is why all superheroes have Daddy issues.

So I think Mr. DeCamp was simply writing at a time when psychobabble was all the rage.

(And if anyone thinks that sort of thing no longer happens: how many of you know your Meyers-Briggs personality type and believe it’s a useful predictive tool for your interactions with others? Somewhere Mr. DeCamp is laughing at you.)

Lewis Terman, a researcher and highly influential pioneer in educational psychology (he created the Stanford-Binet IQ test) got it into his head to study about 1,500 high IQ children. He monitored them from youth to old age. De Camp was one of the gifted children.

De Camp explains in Time and Chance: “In 1922, when I was at Hollywood High School, Doctor Terman gave intelligence tests to 160,000 California school children. From the results, he and his staff chose 1,500 high scorers. During the ensuing decades, they followed these subjects and their careers to see how far the tests could predict a subject’s success in school and in later life.”

A good book on Lewis Terman is Terman’s Kids by Joel N. Shurkin. De Camp is mentioned briefly. The book concentrates mostly on Terman and how his research was often flawed by his interference in the children’s lives. One of the most lucrative successful of “Terman’s Kids” was Jess Oppenheimer, the creator of the I Love Lucy television show.

De Camp, again from Time and Chance, tells of one of his follow up meetings with Terman: “Citing my own personality problems, I asked Terman if I should have myself psychoanalyzed. He answered, “No. For one thing I don’t think you need it.”

This was around 1949. De Camp was a successful writer, happily married, a proud father, and he had a circle of colleagues with whom with he shared professional and personal experiences. No doubt, Terman was correct, de Camp had a pretty good life.

But de Camp mentioning personality problems raises an eyebrow. One of de Camp’s best short stories is “Judgment Day.” (I wrote an article about this story a few years ago comparing it to REH’s “The Supreme Moment.”) De Camp stated it was one of the most autobiographical stories he ever wrote.

The main character in the story is Wade Ormont. Wade, as a child, was skinny, stubborn, and precociously intellectual. At school he was bullied and held lifelong grudges against his tormentors. Wade takes notes of people talking (similar in the way it is said de Camp took notes of conversations to find humor.) Wade grows up to be a scientist and discovers a simple way to start a nuclear reaction. Publishing his paper on the subject will almost certainly allow some goofball to destroy the world. He publishes the paper.

The story is similar to REH’s “The Supreme Moment.” With increasing study it becomes clearer that de Camp and REH were quite a bit alike in certain ways. An obvious example is the way de Camp sympathized with REH’s views on bullying, and always spoke highly of REH’s exercise regime turning himself into a man of mostly solid muscle. I understand why de Camp was attracted to REH and especially Conan.

Lewis Terman published The Gifted Child Grows Up in 1947. This is two years before the previously mentioned visit. The book does not identify any of the subjects by name. I believe, but can’t be 100% sure that de Camp is discussed on page 102 as subject M234:

“M234, who is at the upper level of category 2 [some maladjustment], has had considerable success in his chosen field. His college record was excellent, and he has held fairly good positions. However, his personal adjustment has always been unsatisfactory. He grew up avoiding sports and the usual recreational pursuits of boys, and devoted much time to reading, with the result that he developed an introverted, withdrawn personality, which made social contacts difficult. In his relationship with others he is on the defensive and sometimes gives the impression of being hostile or unfriendly. Endowed with a certain cleverness and wit, he has used it to the point of rudeness in compensating for his sense of inferiority. These feelings of inadequacy extended to matters of sex. He sought psychiatric help for this problem and a few years later was married. Professional success and a happy marriage have done much to help, but there appears to be sufficient basic weakness in his personality adjustment to make his rating 2. He was not called for military service because of his important scientific work in a war industry.”

Again, I can’t be 100% sure, but it sounds like de Camp or at least Wade Ormont to me. If it is not about de Camp, then it at least shows the type of intense psychological scrutiny the “Terman Kids” were subjected to.

There is no doubt in my mind that de Camp’s experience of being under Terman’s observation made him susceptible to observing others with the same scrutiny. Like it or not, de Camp called things as he saw them. As Asimov said, “even when he disagrees with me, he does so honestly, logically, and calmly.

Oh Sublime Eugenic Seeder of the Eons: You don’t know how much this means to us that you showed and wrote this very long comment.

Can it be?!? YES! The Seeder of the Eons has blessed us with His Sublime Presence on this day, as foretold. To wit: “Lo, for the Seeder shall make his presence known to the Elect upon the Day of the Saving of the Light.” — Farr-Nash-Finn the Atheling.

To quote Dunsany from an unpublished, perhaps lost, letter to Arthur C. Clarke:

“Amongst the Mussulmen, God is given but ninety and nine names. Nine hundred and ninety-nine are the names of Gary.”

Let us all celebrate the Year of Gary, the best son Spraguey never had.

However, Gary is wrong if he thinks this person discussed in The Gifted Child Grows Up is de Camp. De Camp did serve in the military; he commented that he was slightly uncomfortable in his naval officer’s uniform around Robert Heinlein, who had been to Annapolis but had been turned down for service due to health issues and other complications.

-

I kinda interpret what Terman wrote:

“He was not called for military service because of his important scientific work in a war industry” as maybe saying M234 wasn’t drafted for combat because he was performing scientific work. Terman always tried to disguise/generalize his subjects a bit when writing about them.In any event M234 is a similar guy to de Camp. Did you ever read Phillip Farmer’s description of R. Dubious Warfield? (A parody of de Camp.) It fits M234 like a glove.

De Camp came from a time when many people that that Freud’s theories explain everything about the world. Now in the case of REH, we have a man who kills himself just after his mother died. Now Freudian is not going to miss all the Freudian symbolize of this act.

De Camp was an example of the type of hard SF writer that Campbell wanted. He also saved REH’s manuscripts and kept the S&S genre alive for future generations to enjoy.

“[De Camp] also saved REH’s manuscripts and kept the S&S genre alive for future generations to enjoy.”

Where did you learn that? From one of Spraguey’s self-serving intros? What an amazing man LSdC was. If you didn’t know better, one would get the impression from de Camp’s writings that men like E. Hoffman Price, Robert Barlow, August Derleth, Glenn Lord, Fritz Leiber and Don Wollheim never existed or had very little to do with preserving REH’s typescripts or with the rise of the S&S sub-genre. Funny how that works.

He sounds like insecure, envious little creature.

Also, that praise of Dunsany’s character feels out of place. Kinda makes me want to apply this guy’s method on him, and write how he yearned for traditionally masculine, aristocratic daddy figure.

De Camp’s smug sniping at his betters via baseless, posthumous psychological blather is only marginally less odious than the same sort of speculation from shrinks with actual degrees. For all their reams of observation and theorization, psychologists still know very little about the workings of the human mind. Some psychologists are helpful not because they’ve studies psychology, but because they’re good “people persons.” Psychology is a non-science.