The Dai Sword, by Manly Wade Wellman

Thursday , 10, August 2017 Appendix N, Fiction, Short Fiction 8 Comments

“…Let the scholar take steel, smelted according to the previous formula, and by his understanding skill beat, grind and sharpen it into a sword. Let it be engraved with the words and symbols ordained, and employed in the performance of mysteries. Let none touch, save those deserving…”

* * * * *

While visiting a merchant with his friend Everitt, John Thunstone is offered a chance to purchase a rare jeweled Nepalese sword. Known as a Dai sword, after the sect who crafted it, the weapon has a jewel in its pommel that entrances Everitt, who draws the sword from its scabbard. The blade turns in the young man’s hands, drawing blood. Thunstone immediately refuses to purchase the blade. Everitt, however, leaps at the opportunity. Worried by half-remembered legends, Thunstone turns to an old Gurkha friend to learn the secrets of of the Dai sect. But most chillingly, Thunstone finds the secret to crafting the Dai sword in the spellbook of his most hated rival, the sorcerer Rowley Thorne. Accompanied by the merchant, he rushes over to Everitt’s, only to find the young man killed by the sword in his hand. Now the Dai sword must be sheathed, but first, it must draw Thunstone’s blood…

Thunstone escapes bloodshed through the silver swordcane at his side. His fencing bests the merchant who crafted the Dai sword, and his blade, crafted by St. Dunstan himself, cuts through the blood-thirsting enchantment in the pommel’s stone.

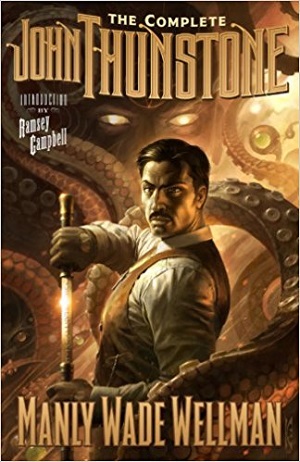

Those more familiar with Manly Wade Wellman’s John the Balladeer may be surprised to find his complete opposite in John Thunstone. Where John was a humble Army vet roaming the Appalachians with his silver stringed guitar in search of rare songs and rare sights, Thunstone was described inside the jacket flap of Wellman’s Lonely Vigils as:

“a hulking Manhattanite playboy and dilettante, a serious student of the occult and a two-fisted brawler ready to take on any enemy. Armed with potent charms and a silver swordcane, Thunstone stalks supernatural perils in the posh night clubs and seedy hotels of New York, or in backwater towns lost in the countryside– seeking out deadly sorcery as a hunter pursues a man-killer beast.”

Where John the Balladeer’s stories always had an air of community to them, Thunstone is often alone, with many of his acquaintances falling victim to the occult menaces he faces. Silver John relies on the knowledge of those around him and the knowledge he knows, Thunstone relies on books, letters, and correspondences, following the conventions of Weird Tales as one of the last homes of Gothic-influenced fantasies. (Early Gothic novels often used the exchange of letters as a form of early narration.) The Balladeer had to rely on reasoning under pressure as he braved the otherworldly mysteries around him, while Thunstone could rely on reams of leisurely research. Where courting and unwanted suitors often filled Silver John adventures, Thunstone’s are solitary and academic. But both men named John would not back down from a fight, whether against men or the dangers hidden throughout the world.

“The Dai Sword” is a more direct story, without the twists that characterize Wellman’s Weird Tales stories. It’s a straight line from the sword’s first cut to the final showdown, interrupted only by Thunstone’s investigations into Dai culture and swordmaking. But like many a simple story, the execution is key, and “The Dai Sword” drips with vivid description that begs to be read aloud. It is also a rare Wellman chinoiserie, mixing Hindu, Nepalese, and Cambodian inspirations in this tale of a cursed sword. The sword fight at the end reflects Thunstone’s technical and precise style–with a weapon at least. And, because “The Dai Sword” was written after 1940, it lacks the sensationalism found in such weird menace tales as Norvell Page’s “When the Death-Bat Flies”. The mystery here is academic and gentlemanly, with the menace of the blade always at a distance from Thunstone instead of ever present over his head and without Wellman’s normally vivid bestiary.

Wellman mentions E. Hoffman Price in the story–and not without reason. Thunstone’s description of the old pulpmaster as “an accomplished fencer [who] understands swords thoroughly” and a recognized student of the Orient can be confirmed though Price’s memoirs and recollections in his Book of The Dead. Skilled enough in Arabic to challenge Lovecraft on the origins of the Mad Arab, discerning enough to choose a proper Persian rug for Farnsworth Wright, and a writer of Chinese-inspired fantasy, Price was well versed in the inspirations for chinoiserie, from Byzantium to Beijing. Price would not be the first of many Weird Tales authors and characters to appear in Thunstone’s adventures. Seabury Quinn’s own occult investigator Jules de Grandin would maintain a correspondence with Thunstone and his teacher, Judge Pursuivant. Rather than creating a shared universe as one might do today, Wellman was content to give the occasional nod to his Weird Tales brotherhood.

Unfortunately, like much of Wellman’s bibliography, John Thunstone’s adventures are out of print, despite some truly amazing–and now expensive–collector’s editions published in the last twenty years. Hopefully, his estate will soon take advantage of the ebook revolution and make these stories more accessible to the general readership. Until then, “The Dai Sword” can be found at many archive sites such as SFFaudio’s public domain page, along with thousands of other short stories.

Complete Thurnstone short stories are available on Audible, as “The Third Cry to Legba and Other Invocations”. Narration is quite excellent, if I dare say so myself, with the exception of the accent narrator gave to Shonokins – it makes them incredibly grating to listen to.

Interestingly enough, one of the final Thunstone shorts – The Last Grave of Lill Warren – reads like a John the Balladeer yarn trough and trough: environment, lyrical feel, Thunstone’s own actions. It was written about the same time when he was starting with John the Balladeer, so one character probably ended up seeping into another.

You can see this same element of modern secular westerner who fails to appreciate an object of different, ancient tradition in “The Golden Goblins”.

There is often this element of respect for other cultures that is far different from the feigned PC one that is common in our modern genre fiction. John will seek help from a well read black priest when dealing with voodoo, another time he will work together with an Eskimo shaman…

Thunstone was a bad-ass. It may sound like heresy, but I slightly prefer Thunstone over the Balladeer in some ways.

Funny thing, but two of my favourite Thunstone stories happen to be ones with least Thunstone in them: one is “Dead Man’s Hand”, other one is the one with soldier, his double and all sorts of occult goings-on in one bookshop’s basement. Thunstone has his active role only in the very end of the former, and latter is told through first person POV of another character.

A great write up…i hope the books would be readily available to readers onlinE aside an archive site.