The Dead Zone. A classic Christopher Walken film from 1983, featuring not just one of Stephen King’s better stories, but also a gorgeous Brooke Adams, a heart-wrenchingly beautiful Apple II, and the awe-inspiring 1970’s edition of Mastermind– they one whose cover features a cunning high powered business man doing the Mr. Burns while his sultry Asian femme fatale consort glares at you over his shoulder.

The Dead Zone. A classic Christopher Walken film from 1983, featuring not just one of Stephen King’s better stories, but also a gorgeous Brooke Adams, a heart-wrenchingly beautiful Apple II, and the awe-inspiring 1970’s edition of Mastermind– they one whose cover features a cunning high powered business man doing the Mr. Burns while his sultry Asian femme fatale consort glares at you over his shoulder.

It’s an enjoyable movie. And I do like how some of the older elements of fantasy and science fiction hang on into the eighties. The science fantasy of Krull and The Dark Crystal is one example of this. The extreme Frazetta-ness of the sword and sorcery cartoon Fire and Ice is another. What does The Dead Zone have…? The slow-to-boil pacing of a Jaws or Rocky.

These older movies lack the uber-safe contemporary formula that has been drilled into us over the past couple of decades. Rather than leaning on frenetic action to hold the viewer’s attention, a combination of character, chemistry, acting, and plot is primary. The overall effect is like the difference between being blasted by somebody else’s favorite albums and enjoying live music in a small venue. It’s the difference between a performance and mere spectacle. I come out of the movie theater these days feeling like something’s been done to me rather than feeling like I’ve been brought into something. It’s wearisome.

Now, I say all that in order to convey the fact that I do not hate this film. I liked it. I enjoyed it. I think it was well worth the four bucks I spent to rent it. If you missed this back in the day, it’s well worth looking up if you’re in the mood for something different. (If you want to see what the best of early eighties horror was like, then definitely watch this rather than the funhouse mirror maze version of it that is presented horrible series like Stranger Things.)

But a question comes up from time to time regarding Stephen King’s relationship to the Lord of Fantasy himself, the early twentieth century grandmaster of weird horror, Abraham Merritt. Generally, it’s fans of Stephen King that wander into discussions about pulp fantasy and Weird Tales and think, “hey… that sounds like Stephen King’s work.” Then they want to know. They have to know: Is Stephen King “pulpy”? Is Stephen King “old school”? Is someone that is really into Stephen King novels hip and cool and winsome and smart in the same way that someone digging through old pulp magazines is hip and cool and winsome and smart?

I hate it when this happens, to tell you the truth. Because the answer to those questions is “no,” “no,” “no,” and… lemme think for a second here… umm… okay, it’s “no.” And fandoms being fandoms, no friendship can survive this sort of revelation. Not even those of the tenuous internet variety. Feelings get irreparably hurt.

What then is the difference between Stephen King’s work and the sort of horror that sold like hotcakes back in the twenties? Well I’ll tell you:

- The ominousness of the surgical scissors being used to menace the viewer with…? Gosh, it just leaves me cold. That’s not the sort of thing Merritt would rely on to produce his effects. And the ick and gore factor of a psychopath committing suicide when he’s finally been caught by the authorities…? After doing a deep dive into pulp fantasy, this really does come off as cheap, tacky, and anti-climatic.

- Also, the boobs. Everybody loves boobs. It’s not going to be a big revelation when I say that a psychopath ripping off a helpless girl’s bra is across the line even in the “spiciest” of twenties style pulp stories. But seriously, go look at those old pulp covers. The scantily clad damsels on the verge of having something terrible done to them? It’s there to draw in the reader… to impel the action forward. But no one’s going to show up to save the girl in Dead Zone. You’re not even supposed to want that. Because it’s a fundamentally different type of story from the old pulps.

- Now… Lovecraft has a great many characters that I would characterize as “New England rednecks.” And I have no problem with people in Maine and so forth having adventures and playing their part in horror stories. But watching this, my question is… where in the heck did the Moral Majority “family values” Senator with the Southern accent come from? It is completely out of place in the snowy wasteland we occasionally glimpse.

- Granted, this film combines science fiction and horror in a way that is more typical of the Weird Tales era. But the key science fiction thread here is the one that has been done to death since some time in the forties: the Dr. Strangelove plot of crazy right-wing militarists that are going to start World War III and destroy the earth. If you want to do a pulp style fantasy/horror/science-fiction mashup, you’re going to have to find another plot besides this one!

- And the Christians. What is it with the way they are invoked here…? They are like props or furniture. Stock characters. They are the picture of normalcy. Conventionality. Blandness. Even stupidity. The protagonist stands apart from it or in contrast to it. You see this in everything from Asimov’s stories written under Campbell to The Last Kingdom on television. One place you don’t see it is in pulp stories from the twenties and thirties.

This is of course going to be completely unpersuasive to someone that is both immersed in and satisfied with a post-Christian world view. They see works of writers like Stephen King as being the baseline. They see writers like King as being the heir to the pulp greats. They see all the various distinctives of pulp literature as being outliers of the genre. Vestigial organs that had to be sloughed off for the medium to properly evolve.

And hey, everybody’s entitled to their own opinion. You love Stephen King novels? Great, knock yourself out! But that’s not what this is about. The question is whether Stephen King is pulpy and old school. The question is… does he have anything like the cachet of an A. Merritt? He isn’t and he doesn’t. And the difference between him and Merritt is like night and day.

Nowhere is this clearer than in King’s handling of the romantic element of this tale. The protagonist starts off head over heels in love. She wants him to stay the night. He wants to save that sort of thing for when they get married. But alas, a car wreck puts him in a coma for five years and he comes out having to endure seeing her married to another guy.

The kind of cringe-inducing scenes where Christopher Walken pretends to be so happy for her and so charmed by the child she’s had with another man…? It’s as foreign to the pulps as it is ubiquitous today. (It’s not just Stephen King characters that are routinely put through these paces. It’s Superman, too, at this point…!)

Now we are supposedly living in more enlightened times where we can finally have all the nudity and explicit sex scenes we can handle. The prudes that kept the pulp literature decent and tasteful back in the day…? They are long gone! Some things are worth waiting for, though. Now that we can cut loose, what do we get?

A broken man in a broken body… his former sweetheart showing up on his doorstep even though she is married and has a son with another guy. And this guy has waited his whole life for this. And she still likes him even though life has moved on from what it was and what it could have been. But there it is: a brief moment of pity sex for a lonesome loser “blessed” with a curse, heading towards a future filled both with alienation, isolation, and despair.

A broken man in a broken body… his former sweetheart showing up on his doorstep even though she is married and has a son with another guy. And this guy has waited his whole life for this. And she still likes him even though life has moved on from what it was and what it could have been. But there it is: a brief moment of pity sex for a lonesome loser “blessed” with a curse, heading towards a future filled both with alienation, isolation, and despair.

What a let down.

Sitting through this, I’m not sure Stephen King could even imagine real pulp horror. And if the old stuff is so facile and formulaic, so predictable and amateurish… I have to wonder why so few people today can compete with the old masters. A. Merritt might have (as Damon Knight noted) “looked like a Smoo.” And say what you will about his prose, but the guy could actually conceive of heroes that were not only worthy to reproduce, but who could also convincingly grab the ultimate “happily ever after” with first rate, classy dames.

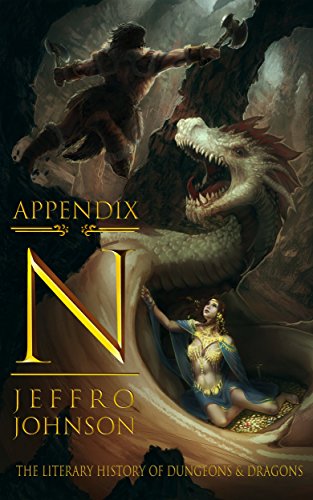

Like the other creators in Gary Gygax’s Appendix N list, he was a better class of author. And he wrote for a better class of reader.

Well, it’s been said before, not just that the folks are happy with the post-morals post-tradition, post-everything worldview, but that they think it is superior, and whatever her name is (Octavia Butler, now that I think about it) is better than Lovecraft. The actually think they and their stuff is BETTER. Mind blowing. And Sad!

The main problem that I see with Stephen King in particular and modern horror in general is an inability to write a Good that deserves to conquer Evil.

The modern horror protagonist is, at best, less bad than the monsters. In the more splatterpunk side of the genre, the protagonist is not even that–he’s just the one who ends up with the bigger gun at the end of the day.

This is not to say that a horror hero must be a saint, but simply that the things for which the hero is fighting–the security of his home and family, the safety of the population in general, or even just his own life–should be acknowledged to be not just his own preferences, but objectively worthwhile.

Moral relativism nerfs horror. If Joe is trying to stay alive and Blargdor is trying to kill him, the author should take a stand and say, “Joe is right to want to live and Blardor is wrong to want to kill him.”

Instead, modern horror writers rely on increasingly gruesome depictions of violence and cruelty to try to awaken the reader’s sense of moral outrage.

It is from that sense of moral outrage that the horror genre gets its power. A hurricane can kill people and destroy property on a great scale, but a hurricane is not a monster. (Granted, you can write a ripping yarn about people trapped in the path of a hurricane and struggling to survive, but it’s not horror.)

To be monstrous, the antagonist must be not merely hazardous, but also wrong. Wrong in an objective sense–Something That Should Not Be.

It is in the deliberate fostering of a sense of injustice that a writer invokes true horror. Killing a monster has to more than personal survival, it must be in itself a morally positive act.

Injustice, however, requires an objective standard of justice to be measured against, and that is something that few modern horror writers are willing to portray.

-

Right on, Misha. The “old-fashioned” conflict you describe is absolutely at the core of Merritt’s BURN, WITCH, BURN which both Bloch and Karl Edward Wagner praised.

Lovecraft liked to do some hand-waving in his tales about the insignificance of moral codes versus a vast and uncaring cosmos, but reading tales like “The Dunwich Horror” and “The Thing on the Doorstep” absolutely demonstrate that WRONGNESS of his eldritch entities.

Lovecraft found the concept of cosmic ambiguity quite disturbing. You can see it again and again in his tales and comments in his letters. IMO, he introduced it in his stories — at least unconsciously — because it produced horror in himself. Modern-day hacks like King don’t know WHAT they believe enough to BE horrified by a blasphemous violation of the moral and cosmic order. It’s said that pros learn the rules and then break them. How can you have horror if there are no rules to break?

-

I had a hand in writing a Lovecraft pastiche (“Special Order,” from *The Disciples of Cthulhu II* as well as an audio adaptation by the Atlanta Radio Theatre Company {end shameless plug}) in which the heroine was rescued from an incomprehensible evil by an equally incomprehensible good.

We were careful to point out that she had no idea whether she’d been saved by an angel, a cop, a PETA activist, or something else altogether. It didn’t matter. The butthurt was palpable. Apparently Lovecraft fans *like* the idea of a nihilistic universe. More than he did, I suspect.

-

-

Stephen King is kind of an odd duck. He rejects organized religion, but claims to believe in God. His straight horror novels tend to be bleak and hopeless, although he subsequently disavowed CUJO and PET SEMATARY for going too far in that direction.

His fantasy novels have a clear conflict between good and evil, heroic albeit grim protagonists, and a vaguely Christian cosmology with elements of Hinduism and Native American religion. Salvation or grace is conspicuously absent. His protagonists usually prevail in the end, but pay a terrible price.

-

I think there’s a lot of self-loathing coming from his years of drug addiction.

-

Lovecraft depicted rational secular men going mad when discovering the universe was not rational or secular at all but in fact the complete opposite.

Howard depicts a faithful man (Conan) braking a magical swords on the back of a demon then slaying it with the shard left on its hilt.

King depicts rational secular men getting all rational-voodoo-macgyver in the face of the supernatural and then depicts Christians, lifetime believers of the supernatural, as somehow being wronger. Often being paralyzed into prayer or becoming mad or cynical Inquisitionists.

Two of these feel as natural as rain one feels brewed and formed from scraped sewer drain plaque of a plastic injection mold factory.

Despite his occasional swipes from Lovecraft, I’ve never connected King with pulp fiction. Whenever he talks about writers of that era, it seems more out of politeness than any real enthusiasm. He’s much more into his immediate forebears such Shirley Jackson or Richard Matheson, I think.

I enjoy King’s stories to an extent (I just read Salem’s Lot recently – a good vampire book. The priest of course turns out to be a drunk with weak faith…) but there’s something facile about his work and his worldview. To use a silly example, whenever he talks about music it becomes clear that he’s not a deep cuts sort of guy. His favorite BOC song is Don’t Fear the Reaper, his favorite AC/DC is Back in Black, his favorite Metallica is Enter Sandman, etc. It’s all sort of lazy and obvious. Maybe I’m not making sense…

-

Makes sense to me. While not lacking talent, King tends to be lazy, obvious and shallow. He is definitely not a cheerleader for the pulps like he is the newer authors you named. King has even taken swipes at the READERS of Robert E. Howard. Doesn’t get lamer than that.

King did admit reading and liking Merritt back when he was a young hack-to-be. He should’ve paid more attention.

I’ve read King (including Cujo), Koontz, Lumley and Laurelle K. Hamilton, among others, and some of them are quite good, but I prefer Merritt and Lovecraft.

I’m not saying those authors are bad, although I agree with deuce’s assessment of King. I just think that A. Merritt and HPL were better.