The Forsaken Sequel: The Unforsaken Hiero

Monday , 1, May 2017 Appendix N, Authors, Book Review, Fiction, Uncategorized 8 Comments Appendix N entry Hiero’s Journey by Sterling Lanier is one of my favorite books. A thrilling masterpiece of fast-paced creativity and high adventure from start to finish. Its protagonist is Hiero Desteen, a powerful telepathic Christian warrior riding a “morse”, a mutation of a moose and a horse, in a post-nuclear wasteland filled with oddities, horrors, and endless danger. He befriends a telepathic bear, fights the nefarious Brotherhood of the Unclean, and saves a half-naked black princess.

Appendix N entry Hiero’s Journey by Sterling Lanier is one of my favorite books. A thrilling masterpiece of fast-paced creativity and high adventure from start to finish. Its protagonist is Hiero Desteen, a powerful telepathic Christian warrior riding a “morse”, a mutation of a moose and a horse, in a post-nuclear wasteland filled with oddities, horrors, and endless danger. He befriends a telepathic bear, fights the nefarious Brotherhood of the Unclean, and saves a half-naked black princess.

In a perfect world, Sterling Lanier would be more famous for writing Hiero’s Journey than for championing and publishing Dune, impressive as that contribution was. Jeffro did a fine job analyzing the book in Appendix N: The Literary History of Dungeons and Dragons, including spotting the blemishes I either missed or ignored in my youth.

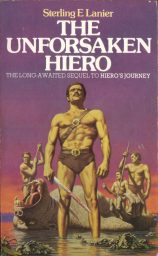

However, this is not a review of that classic, but its far less-heralded sequel, The Unforsaken Hiero.

Published ten years after the original, in 1983, it was surprisingly difficult to find. I located it in the same place I have many obscure science fiction and fantasy works; in an online library on the Russian Internet.

Jeffro mentioned that in the original, Hiero’s rescued damsel Luchare being a princess was irrelevant to the plot. Someone must have informed Lanier of this same fact, because the sequel, after a brief introduction and recap, has Hiero and Luchare traveling to her father’s kingdom in the south.

I wish it had stayed irrelevant.

The king is a bore. The descriptions of the society bare-bones and superficial, but far too long. The few named characters can safely be forgotten. The villains, who Hiero is not able to figure out before it’s too late, should be immediately obvious to even the youngest and most inexperienced reader. Unlike the originality and exuberance of Lanier’s post-apocalyptic wilderness and animals, his human societies are bland and colorless.

Amusingly, the lone, bright exception is the hopping, kangaroo-like creatures that the military rides into battle. So again, the animals.

The beginning also features a jarring, even immersion-breaking passage;

When they had passed, another company approached, this time a caravan of gaudily clad merchants newly come from the South and stained with travel. Some bore the marks of recent battle, and Hiero knew they would report, as all travelers did, to the court newsmen, whose business it was to know and collate whatever passed throughout the kingdom. Many of these newcomers bore a six-pointed star as a symbol, and Hiero knew them for Davids, the other odd religion of his new country. They seemed identical to all their fellow citizens, being both rich and poor and occupying all places in society. But, though believers in the one God, they had no prophets or saints at all, their priests relying only on certain secret books, never shown to any but coreligionists. Both they and the Mu’amans held high places at court, and some were hereditary nobles; but in private life they kept much to themselves and seldom intermarried with the mainstream of Christianity. Yet Lu-chare and Danyale trusted them implicitly. “I wish I could be as sure of my fellow churchmen as I am of the Davids and the Mu’amans,” the king had said bleakly. And indeed, many of both were in the royal guard and the local militia units which made up the realm’s army when assembled.

Why was this included? These hamfisted analogues of the Jews and Muslims are never mentioned again.

Despite the rough beginning, the book picks up when Hiero once again finds himself trekking through the wilderness. There, he must rely upon his Christian faith to survive, and Lanier, trained anthropologist and cryptozoology enthusiast, allows his imagination to run wild in creating fantastical flora and fauna.

The descriptions and battles, while not on par with the original, are nevertheless vivid and exciting. And this is where the book keeps getting better and better, culminating in Hiero being mentally pulled to an ancient, abandoned valley by a strange being. Here is what he beholds;

Stretching out around them as far as they could see was a shore of bones, moss-covered and old, with a few whiter and newer additions. They had come upon a graveyard of a strange and horrible kind.

How many generations, how many lives of the world outside, must have been spent to create that vast and moldering wrack of skeletons, not even the inhabitant of the lake could have said.

There was no discrimination among the relics of the past. Skulls of the giants, with crumbling tusks many yards in length, were piled in heaps, mingled with the slender crania of the hoofed runners on the grass. Savage fangs, half-buried under the lichen and mildew, showed that meat eaters were not exempt. The femurs and hoofs, the occipitals and astragali of hordes of smaller beasts were inextricably entwined through and over the huge ribs and metacarpals of the greatest brutes. From dead eye sockets, the ghosts of reptiles stared in empty equality at the mammals. All of evolution had met in the common fate of their mortality. The only conquerors were the dampness, the mold, and the swirling mist. The only epitaph was silence.

This scene, and what follows possesses an incredible majesty; a hero standing before the bones and ghosts of the mighty past. And meeting the titanic, unique being who has lived through all of it. It was here, regardless of the content before or after, that the book hit an exceptional high point for fantasy, right up there with anything in the first book. There might be few such moments in The Unforsaken Hiero, but they make the book memorable and worthwhile.

Later on, Hiero gets involved in more adventures. There is a town plagued by an unseen force the villagers are convinced are ghosts and must be placated. The reality is even stranger. This episode reads like a good mystery mixed with life-and-death combat and fantasy.

This part of the book is not without its flaws, though. In the original Hiero’s Journey, we only get brief glances of the villains, The Brotherhood of the Unclean, through Hiero’s eyes. Thus, while we know they possess tremendous telepathic powers, inventions, influence, and malevolence, they remained mysterious. As with Luchare’s royal roots, it should have stayed that way.

In the sequel, we get an omniscient third person narrator’s view of the Unclean’s highest, innermost councils. And far from being a group of brilliant, confident villains, they resemble a bunch of squabbling, peevish, lower-level minions. They’re constantly blaming one another for failures, offend each other, and have a comical, superstitious fear of Hiero. They reminded me of a group of bickering old wives rather than supremely powerful warlocks that have possibly lived for centuries.

Not only is this disappointing, but it makes Hiero’s struggle against them less engrossing and suspenseful. After all, since the antagonists come off as inferior to the leaders on Hiero’s side, Abbot Demero and Brother Aldo, why would they have trouble defeating them? One doubts how big of a threat they really are.

Near the end, Hiero meets up with members of his own nation, the Metz Republic, and we are treated to several large-scale battles. The first, a naval engagement, is picturesque and memorable, doing a particularly fine job of describing a burning town being bombarded and the ensuing panic.

The last one is the climactic battle against the Unclean, with each side gathering all available allies. This, unfortunately, is very underwhelming. The description is bare-bones, the clash has few surprises, and Hiero plays a seemingly insignificant role, his military rank aside. The book ends with a whimper instead of a bang.

Thus, the sequel features a poor beginning and a lackluster ending, but a very good middle portion that occasionally hits dizzying highs.

It also bears mentioning that the book has an odd perspective. On the one hand, it has a distinctly Christian hero frequently relying on his faith to survive. One of Hiero’s later allies is a young priest whose most powerful trait is his radiant holiness, having an especially close connection to the divine, and thus able to see the future. On the other hand, it has the aforementioned, silly virtue-signaling about other faiths being good.

There is also a nauseating feminism, with women in the Metz military being just as competent and tough as the men.

And yet, there is an astonishing passage in support of racial homogeneity. The Metz Republic’s major advantage over the neighboring Otwah League is the purity of the Metz blood. The Otwahns, having more racial diversity, are less united, and have more internal bickering.

How this jives with Hiero marrying the black princess Luchare, or the easy intermingling of various tribes and kingdoms that is seen as natural, is anyone’s guess.

Overall, even with the flaws, the book’s strengths make it a decent read. I would recommend it to others who loved Hiero’s Journey, although one shouldn’t expect the same level of quality. Those with cooler feelings about the original can likely skip it.

It’s a shame the series ended the way it did. Lanier had originally planned for it to be a trilogy. On a curious note, there were apparently some unofficial Russian sequels released after Lanier’s death in the later 2000s. No clue on whether they are any good, but like me, the authors came to the conclusion that there were many more adventures to be told of Hiero Desteen and his post-apocalyptic world.

I loved the first book in the series. Flaws notwithstanding, I really need to dig this one up.

https://everydayshouldbetuesday.wordpress.com/2016/09/08/throwback-sf-thursday-hieros-journey-sterling-lanier/

Truth be told, I am yet to read the first one. (and I suppose that I am not alone, given the lack of comments9 It is in the context of Appendix N that I’ve heard of it in the first place, probably around here.

Though, I think that we’re all beyond expressing surprise at something that was once widely read falling into near complete obscurity.

Props for bringing forward Sterling Lanier. I read both books years ago and enjoyed them both! Lanier is rather obscure, have you ever read anything by Frank Stockton? He might be worthy of your consideration.

Long ago, I read the two Hiero books. I agree there’s a drop-off in quality with the second novel. Lanier’s Metz Republic being racially homogenous is mildly amusing, since the “Metz” itself is a reference to the Metis of Canada. I assume that Lanier was referring to the fact that the Metis/Metzans had a strong, single ethnic identity while the Otwan state contained several ehtnicities.

It’s been a long time, but I recall enjoying Lanier’s MENACE UNDER MARSWOOD more than the second Hiero book:

https://vintage45.wordpress.com/2015/11/18/menace-under-marswood-sterling-e-lanier-1983/

I wish SEL had lived to publish No3 . Both journey and unforsaken are magnificent . My first copy of Heiro’s journey has long since disintegrated and I, like many of you ,would love to know the end.