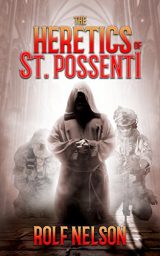

The Heretics of St. Possenti, by Rolf Nelson, presents the story of a disillusioned bishop heading off into the American backwoods to establish a monastery dedicated to the usual sorts of monkish activities. You know the kind: growing their own food, praying at regular hours, singing matins every midnight, studying the bible, learning a trade, practicing close order combat drills, making and selling ammunition on the open market, scaring away Federal officials by using threats of violent resistance…the usual.

The Heretics of St. Possenti, by Rolf Nelson, presents the story of a disillusioned bishop heading off into the American backwoods to establish a monastery dedicated to the usual sorts of monkish activities. You know the kind: growing their own food, praying at regular hours, singing matins every midnight, studying the bible, learning a trade, practicing close order combat drills, making and selling ammunition on the open market, scaring away Federal officials by using threats of violent resistance…the usual.

Wait, what?

The Heretics of Saint Possenti represents the best that literature has to offer. On the surface, it’s the story of how a new monastic order might spring up in these days when civilization teeters on the precipice of the next great turning of the wheel. When presented with the challenge of bringing men, particularly young men, back into the folds of the Catholic Church, Bishop Thomas Cranberry wisely looks to the most vulnerable men in American society – those with nothing left to lose and those most in need of a life line. He finds them in the backalleys and bars of anytown USA, almost all veterans who have been ill served by the country that spent their youth and sanity overseas in the pursuit of vague promises of building a better world. The Bishop approaches the problem of bringing men into the Church in a novel way – by listening to them and realizing that the modern palliatives of “man up”, “drug up”, and “shut the hell up” just don’t work in a country that views them as disposable and that rejects men’s need for camaraderie, physical competition, and quiet contemplation.

After a slow introduction in which Bishop Cranberry simply meets and listens to a cross section of men in his town, he learns that there is far more to modern masculinity than the seminary ever suggested. The lack of action early in the book is counterbalanced by frequent discussions about masculinity that we aren’t supposed to have in these modern, “enlightened” times.

The Bishop closes his mouth and learns from a wide range of men – surprisingly thoughtful men, he finds – and experiences the revitalizing power of strength training and combat sports. Over the opening quarter of the book, he slowly develops a plan so audacious that he dare not reveal the particulars until he has already proven its effectiveness. With a small investment from his local Cardinal, Bishop Cranberry takes the lost men of his town, those heathy enough in mind and body to still desire a way out of their predicament, and gives them something to live for. They find a patch of woods where they can be free to work on themselves – mind, body, and spirit – and where they can help each other recuperate from the trauma of their modern lives.

Interwoven and buttressing the story of the monastery itself are the stories of the men who help the Bishop establish this strange new monastery. Some were chewed up by a military industrial complex focused more on finances than the welfare of the men it claims to serve. Some were ground down by the self-contradictory demands of a culture that demands they be strong enough to surrender at a moment’s notice to the latest whims of the nearest victim group. And some just want to be a part of something bigger than the next quarterly profit report. Their stories are poignant, and provide the glue that holds together a novel that often diverges into philosophical debates about the nature of manhood, self-defense, meditation, sexual mores, and the finer points that distinguish one rifle from the next.

It’s an odd sort of book that sometimes feels like a post-apocalyptic novel, albeit one in which the blasted wasteland that surrounds the monastery is spiritual rather than physical. With numerous digressions into the sort of logistics porn that runs through more traditional post-apocalyptic fare, these passages underscore the valuable effects of self-sufficiency on a man’s psyche. The discussions about firearms, ammunition, and the economies of both fit into the narrative naturally and unobtrusively, with a man’s view of firearms revealing much about his character.

The book also shatters a number of common misconceptions about who monks were and how they lived. Scholars of the post-Enlightment years have foisted onto the public a one-dimensional view of monasteries as grim and soulless places populated entirely by weak men condemned to live out their days in gray drudgery. The Heretics of St. Possenti presents monks as they really were – strong, but often damaged, men seeking escape from the secular world for a time for reasons as varied as the men inside the cloistered walls. Some are stoic and no-nonsense, some are smart-alecs, and some are just not meant for the live of a monk. All have their time on stage, and all bring both joy and sorrow to the monastery as they underscore the hidden costs of society’s destruction of the ties that once bound good men together as a community.

The success of the monastery is shown in a series of third-act vignettes. When the original class of monks completes their term of service and return to the world full time, they act with swift certainty in the face of danger. They confront the challenges of modern life head on, and with the support of other men who have their backs come what may make the world a better place to live. This final vision of men who stand together, for the good of each other rather than as a sacrifice to ephemeral notions of “it takes a village”, is one sure to chill the bones of any globalist-minded reader who manages to survive the preceding two acts that strip away their delusions and show men as they are, not as the left wishes them to be.

It’s not a book for everyone. The close-minded and pessimistic will find their worldview challenged, as will those who view any expression of masculinity toxic. Open-minded men seeking answers – and the women seeking to understand what drives western men – will find this book a fascinating look at everything from friendship to survivalism to religious practice in a secular age and even the politics of the Catholic Church. If you can handle the idea of warrior-monks operating on a cancer ridden culture with all of the bloody tools at their disposal, give The Heretics of St. Possenti a shot – you won’t regret it.

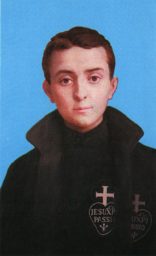

Saint Possenti himself

This review glossed over the striking contrast present in men dedicated to the Church who spend their days practicing close combat, at the shooting range, and working in an ammunition factory. It seems self-evident to anyone who knows the role the Church and its men have played in defending Europe from barbarian hordes of many different stripes, but for those interested in one aspect of that relationship, here’s the story of Saint Possenti, the patron saint of handgunners and the monastery’s name-sake (from gunsaint.com):

In 1860, a band of soldiers from the army of Garibaldi entered the mountain village of Isola, Italy. They began to burn and pillage the town, terrorizing its inhabitants.

Possenti, with his seminary rector’s permission, walked into the center of town, unarmed, to face the terrorists. One of the soldiers was dragging off a young woman he intended to rape when he saw Possenti and made a snickering remark about such a young monk being all alone.

Possenti quickly grabbed the soldier’s revolver from his belt and ordered the marauder to release the woman. The startled soldier complied, as Possenti grabbed the revolver of another soldier who came by. Hearing the commotion, the rest of the soldiers came running in Possenti’s direction, determined to overcome the rebellious monk.

At that moment a small lizard ran across the road between Possenti and the soldiers. When the lizard briefly paused, Possenti took careful aim and struck the lizard with one shot. Turning his two handguns on the approaching soldiers, Possenti commanded them to drop their weapons. Having seen his handiwork with a pistol, the soldiers complied. Possenti ordered them to put out the fires they had set, and upon finishing, marched the whole lot out of town, ordering them never to return. The grateful townspeople escorted Possenti in triumphant procession back to the seminary, thereafter referring to him as “the Savior of Isola”.

Jon:

Thanks for the review. I really should add this book to the queue.

Just a couple of tidbits for our non Catholic friends:

St Gabriel Possenti’s vowed name was Gabriel of our Lady of Sorrow. He never became a pries as he died of TB but did make his vow as a Passionist.

Strictu sensu, St Gabriel Possenti ISN’T OFFICIALLY a patron saint of handgunners but popular piety does play an important roles. I do hope he becomes the patron saint.

Sorry tobe a tad pedantic but I commend Rolf for choosing the saint and reflecting on how the Church and the church fathers throughout the ages have held that bearing arms for self defense and thee common good is licit and legitimate.

xavier

Fight Club for Christians. I am about 25% into the book. It is very good.