The Iron God and The Lair of the Grimalkin

Saturday , 30, November 2019 Uncategorized Leave a comment Jack Williamson’s career in science fiction is long and distinguished, starting with his first story, sold to Hugo Gernsback in 1928, and enduring into the 21st century. He is perhaps best known for his Legion of Space. And, to be fair, I wish my introduction to him was there.

Jack Williamson’s career in science fiction is long and distinguished, starting with his first story, sold to Hugo Gernsback in 1928, and enduring into the 21st century. He is perhaps best known for his Legion of Space. And, to be fair, I wish my introduction to him was there.

Instead, curiosity got the better of me when I saw “The Iron God” in SFFAudio’s Public Domain files. The combination of dive bombers attacking a metal giant and a science fiction story published in Marvel was too much to pass up.

Unfortunately, time has not been kind to “The Iron God”, as its hopeful optimism, mad science, and star child tropes have been ground into dust over the resulting seventy and more years as science fiction magazines, books, and drive-in movies have copied the same themes and plot elements. And the sea change that accompanied post-modernism shifted views about science away from the path to a rosier dawn towards the leading suspect of who will kill our tomorrows. From that vantage point, the clumsy attempt of a mad scientist to create a New Man who would not heed the Old Lies serve more as a warning against secret kings than a reproach of a species that kills what it doesn’t understand.

That said, the reason “The Iron God” does not shine has more to do with the dross that followed it than it’s own faults. At best, it is average. Really, the radioplay of the doomed dive bombers is the highlight.

Pulp fiction’s fascination with Colonel Percy Fawcett continues, as the mad scientist father of the Iron God disappears into the South American jungles. However, it has changed from men of action and science like Doc Savage into brilliant lab rats content with mere moral victories.

I’ll try Williamson again, as his presence inspired and shaped much of traditional science fiction since before the Campbelline Age. But this time, I’ll stick closer to the beaten path

For five years, from 1943-1948, Richard Shaver exploded on the scene with his Shaver Mystery, an X-Files-like set of mysteries filled with secret worlds and hidden cavern cities, much to the frustration of science fiction fans. During this time, Amazing‘s circulation swelled to nearly 200,000 per issue. (Weird Tales and Astounding averaged 50,000) Meanwhile, SF fandom tried to cancel Shaver through boycott and letter-writing campaigns, creating an ugly tradition that still carries on to today. 1948, Amazing stopped publishing the Shaver Mystery, for reasons unclear, and Shaver spent many years chasing after the success he once had.

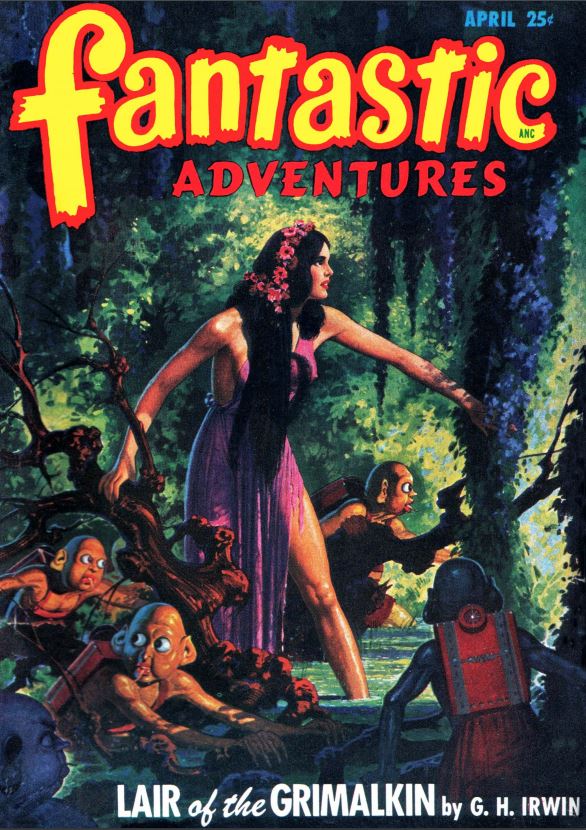

“The Lair of the Grimalkin” is one such attempt under the pen name G. H. Irwin, a sword & planet tale set on Venus. Here, Venus is a green Hell here, teaming with a mix of life and chemicals that limit Earthmen to small sections of the planet. But the lush life covers vast mineral wealth, so men repeatedly set forth into the jungles. They just don’t come back.

Tempted by riches and the verdant hellscape, Hal has a line on a massive deposit of platinum in the well-named Swamp of Despair, and the story begins with preparations for an expedition that’s most likely doomed.

Tempted by riches and the verdant hellscape, Hal has a line on a massive deposit of platinum in the well-named Swamp of Despair, and the story begins with preparations for an expedition that’s most likely doomed.

Then, deep in the Venusian Amazon, Hal finds the rarest flower on the planet–a human woman surviving where explorers never did. Her jungle home is threatened by the Grimalkin, a kind of dragon, so Hal decides to play St. George.

But things aren’t as they seem, as a failed attempt at killing the alien Great One lands them in captivity, alongside the girl, in a Venusian village. Shaver doesn’t bother filing serial numbers off of dragon myths here, so Hal and his companions have to escape–or be dinner. The resulting fight rages across Venus, back to the Earthman domes before the dragon finally is slain, and Hal earns his babies ever after ending.

I was expecting dreck from Shaver, as his memory is maligned even to this day. This wasn’t bad. Frankly, “The Lair of the Grimalkin” holds up better as a story than Williamson’s “The Iron God.” There’s more humanity to this transplanted jungle adventure, for one. Shaver has imagination, to be sure, but he needs an editor. The folksy style doesn’t lend itself well to the exposition needed for worldbuilding and Shaver’s fascination with making up his own language.

For a man who is derided for his fascination with the paranormal, Shaver’s chemistry is surprisingly crunchy. More than one compound and ore that sounded like blatant unobtanium actually exist with the compositions Shaver describes.

There are massive Lost City of Z resonances here, which shouldn’t be a surprise as pulp was smitten with the real-life adventures of Colonel Percy Fawcett, who inspired elements of the adventure pulps, hero pulps, and the weird pulps.

As a result, I would love to see what Shaver might have done in an Argosy-style adventure. He had the formula and the verisimilitude. But the paranormal and the pseudoscientific were instead his fascination–and his reputation among the “notables” of science fiction fandom suffered for it.

Please give us your valuable comment