In early science fiction criticism, James Blish (1921-1975) is generally ranked right behind Damon Knight as one of the pioneers. Blish was part of the left wing leaning “Futurians,” a group of New York based science fiction fans in the late 1930s, though Blish was apolitical or possibly right wing.

In early science fiction criticism, James Blish (1921-1975) is generally ranked right behind Damon Knight as one of the pioneers. Blish was part of the left wing leaning “Futurians,” a group of New York based science fiction fans in the late 1930s, though Blish was apolitical or possibly right wing.

He broke into science fiction magazines in 1940, had a stint in the U.S. Army in WW II and then returned to science fiction after the War. He is probably best remembered today for the Star Trek Log books adapting Star Trek episodes into prose. I was just in the local Barnes & Noble bookstore today and saw a hardback of Star Trek adaptations that included Blish.

Blish wrote scathing book reviews for mimeographed fanzines in the 1950s under the pseudonym William Atheling, Jr. Many were collected into the books The Issue at Hand (1964) and More Issues at Hand (1970).

The tone of these books reviews is very similar in tone to Damon Knight. In fact, Blish said:

“If it’s decent criticism of science fiction that we’re looking for, there is at the moment only one place to find it within our microcosm: In the book reviews of Damon Knight. The book reviews of the professional magazines are seldom better, and usually worse, than the little ghettos reserved for us in the Sunday book section of daily newspapers.”

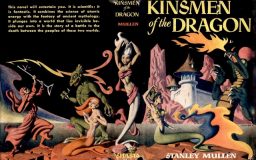

One intersection between the two I have found is both demolished a novel, Kinsmen of the Dragon by Stanley Mullen. Mullen appeared to be a weird  fiction fan, published a small press magazine, The Gorgon, had some stories in science fiction in the 1950s, and then faded out. I have not read the novel but Blish had this to say:

fiction fan, published a small press magazine, The Gorgon, had some stories in science fiction in the 1950s, and then faded out. I have not read the novel but Blish had this to say:

“His plot summary of Stanley Mullen’s Kinsmen of the Dragon for instance, is perfectly suitable to the preposterousness of its content.”

From the synopsis of the novel, Mullen appeared to attempt to use fantasy elements with science fiction explanations. The overpraised magazine, Unknown/Unknown Worlds did this. There were a number of stories and novels including William Tenn’s “Medusa was a Lady!,” Theodore Sturgeon’s “Excalibur and the Atom,” and Lester del Rey’s “When the World Tottered” that tried to explain myth with science.

Blish was vicious when it comes to fiction that he does not “get.”

“I don’t know how else one can account for the grand passions that have been raised by Edgar Rice Burroughs, H. P. Lovecraft, A. Merritt, and a number of technically still living people whom the law of libel forbids me to mention.”

Blish devoted a whole chapter in More Issues at Hand named “The Monstrosities of Merritt.”

“Writers who undertake straight fantasies–defined as stories with a supernatural element which is never explained away, but without, usually any primary intent to horrify–have a marked tendency to tell them through their noses. This habit of intoning is usually attributed to an attempt to create a ‘poetic’ atmosphere, but I think it is equally due to history–that is, the desire to make the end-product sound like Malory, Beckford, or an ancient manuscript. Often, as in the case of H. P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith and A. Merritt, it is disastrous.”

Blish discusses Merritt’s prose style in negative terms. He asks the question:

“Why, then, has this crude performance been so highly touted for so many years? Nostalgia may provide one answer.”

Back in the late 70s, Ace Books used to include generally boring and quasi-academic sounding essays by Sandra Miesel at the end of some novels. “The Mana Crisis” from Larry Niven’s The Magic Goes Away had this to say:

“Logical fantasy is distinguished by its playful attitude toward the fantastic. It stresses ingenuity more than glamour and comedy more than melodrama. It is informal, sometimes to the point of flippancy. It may treat serious matters but without solemnity. The enterprise is fundamentally an intellectual game.”

Taking this tact, Bewitched is superior to Le Mort d’ Arthur.

Blish made some hilarious comments in hindsight. He reviews Poul Anderson’s story “The Immortal Game.”

“Over this mechanical performance broods the spirit of Anderson the Barbarian, Thane of Minneapolis, Bard of Scandinavianism–the side of the writer’s personality, in short, which emerged during his long apprenticeship to Planet Stories. Nobody should need to be reminded that Anderson can write well, but this is seldom evident while he is in his Scand avatar.”

This is in incredible statement. Poul Anderson is a favorite science fiction writer of mine and part of the reason is this “Scand avatar” aspect to him. Anderson breathes some real humanity into his fiction of the future by the infusion of the spirit of the past.

Blish piles on in a footnote:

“Readers debating sword-and-sorcery tend to shed their heads as well as their shirts, as the recent Tolkien craze amply demonstrates.”

James Blish’s “criticism” comes off as being a Minnie Me to Damon Knight’s Dr. Evil. Knight and Blish were acting like commissars purging groups deemed heretical after the revolution. There is a hatred for things that preceded the current (at that time) generation. They attempted to belittle, mock, and expel fantastic fiction did not fall in line with the new orthodoxy. This was a new era of science and those old traditions and superstitions were to be done away with. Their reviews were part of a codification of the narrative that gained hold after WW II.

James Blish’s “criticism” comes off as being a Minnie Me to Damon Knight’s Dr. Evil. Knight and Blish were acting like commissars purging groups deemed heretical after the revolution. There is a hatred for things that preceded the current (at that time) generation. They attempted to belittle, mock, and expel fantastic fiction did not fall in line with the new orthodoxy. This was a new era of science and those old traditions and superstitions were to be done away with. Their reviews were part of a codification of the narrative that gained hold after WW II.

The comments about Poul Anderson or Tolkien are at the least, funny in retrospect if not embarrassing.

Given Blish’s adulation of James Joyce, I was always suspicious of his critical opinion.

-

I usually employ “liking Joyce” as a litmus test myself.

-

And it is quite an efficient, unerring one. Moorcock, for example, once wondered how is it that people tout LotR in century that produced Ulysses!

Joyce is ever so good for detecting certain… types. Only thing he’s good for, actually.

-

Personally, I use “liking anything by Joyce after Dubliners”. (Not that the latter is anything great, but it’s a decent short story collection, which is more than can be said for his later work)

-

Not to turn this into a music blog, but this all reminds me of the academy’s response to ballet music, impressionism, etc.

That is, near the beginning of the 20th century, we have composers like Tchaikovsky, Debussy, and Holst. So the academy responds with Schoenberg, Berg, and Cage. Then composers like Bernstein, Williams, and Hisaishi flee into the motion picture industry and composers like Uematsu, Mitsuda, and Wise flee into video games.

To combat that, they’re now trying to standardize motion picture music so that, for instance, all Marvel movie music sounds like interchangeable generic atmospheric music. No more leitmotifs so that all the heroes are interchangeable.

I never read any of Blish’s novels, so I might be mistaken here, but is it not true that several of them have strong religious and occult element? His “Black Easter” is characterise as occult thriller, and other of his novels apparently mix SF and supernatural. Non of it is characterised as humorous or satirical.

That seems to be completely at odds with distaste for serious supernaturalism expressed in those quotes.

-

Most people differentiate between fantasy and mythology on the one hand, and religion and occult on the other.

He seems to be criticizing those elements of supernaturalism he disdains (doesn’t believe), while being perfectly willing to use those elements he finds palatable (does or could believe).

Perhaps he was afraid of the Norse mythology of Tolkien returning, so didn’t want people using it; while he never believed that occultism would ever get a foothold, and therefore was reasonable story material.https://en .wikipedia. org/wiki/Heathenry_(new_religious_movement)

-

People also like to claim some supernaturalism is for children while others is for adults. (Like polytheism is for children, while monotheism is for adults. Or, magic is for children, miracles are for adults.)

That way, they can say they are mature while you are stuck in youth. Therefore your arguments and values are invalid from the get go.

The idea is to be able to find a way to disqualify your beliefs (or personality) before the debate begins, so they don’t ever have to actually defend their values and politics. -

Well, I can imagine mental gymnastics needed to justify it. Metaphors, way to approach and explore social and psychological issues, etc, etc…

-

Blish is an odd one. He corresponded with Lovecraft and wrote a story using Chambers’ THE KING IN YELLOW. Blish was also a fan of Cabell, who definitely wrote snarky fantasy.

I’ve read BLACK EASTER and it reads “straight”. By that, I mean Blish gives the impression that Hell is real and as depicted in the Bible. His afterword indicates that he researched the occult stuff and took it seriously. He may’ve considered himself some sort of Christian. His afterword would seem to indicate that. His novel about Roger Bacon was certainly sympathetic. An odd man.

https://infogalactic.com/info/James_Blish#After_Such_Knowledge_2

-

“A Case of Conscience” was very much written as this strange take on Christian SF, with shades of “Perelandra” to it.

Funny thing, that novel. First portion of it makes one think how he is getting “demolishment” of strawmanned and simplified Christian outlook, but then, latter on, novel affirms it. Almost as if he wanted to lure atheist SF readers in, and then…It’s a pretty meh novel, mind you, with no artistry to it, and I never seeked anything else by him. But, there’s that.

-

-

Mythos scholar, Chris Perridas, on Blish and HPL here:

http://chrisperridas.blogspot.com/2011/02/james-blish-1937-eldritch-goo.html

I’ve tried reading Blish. Twice. It didn’t take either time. Poul Anderson’s work, in particular his Scandinavian-influenced work such as “Time Lag”, the story we published in There Will Be War Volume II, is vastly better than anything Blish ever produced.

I hope Knight and Blish eventually managed to consummate their bromance at some point. One of the great tragedies of SF litcrit, if not.

Poul consistently infused his SF tales with a tinge of the Norse sagas. One can be reading an Anderson story set in the Crab Nebula or whatnot and then Poul will slip in a simile to wolves or the aurora borealis or a sword. Such prose makes such unseen and, at times, utterly theoretical wonders far more tangible. Asimov, with his “streets of Brooklyn”/Navy shipyard background, never even attempted such things and his leaden prose suffered for it.

Poul had the mind of a scientist, but he was a Romantic at heart. I’ll take him over any of the “Big Three”, even Heinlein. He thought just as big and wrote better. Plus, there wasn’t a major drop-off in quality during Poul’s later years like there was in that of the divine “Three”.

Mike Resnick curbstomps Blish in regard to A. Merritt here:

Who’s the prophet now, Blishy Boy?

This desire to expunge fantastic from genre fiction makes folks like him look remarkably closed-minded and weak. “Art must conform to my own world-view, anything that doesn’t conform to it must be either removed or deliberately mocked.”

“Logical fantasy is distinguished by its playful attitude toward the fantastic. It stresses ingenuity more than glamour and comedy more than melodrama. It is informal, sometimes to the point of flippancy. It may treat serious matters but without solemnity. The enterprise is fundamentally an intellectual game.”

I can’t help but think of that recent article about Gaiman. There is something to be said for how he cannot help but treat anything uncanny, mythological, religious with a dose of irony. I suppose that he’s a true torchbearer of this mindset among speculative fiction authors.

-

I’m sure Gaiman would’ve sold to Unknown, no problem. Unknown was built upon a snarky and “sensible” approach to the fantastic, though there were outliers like Wellman — who got his break in Weird Tales.

Even Anderson’s weaker stuff is still very strong, and RW has yet to read anything from him that isn’t good.

I read not too long ago Blish’s Star Trek novel, Spock Must Die! I believe it was the first official Star Trek novel.

I thought it was okay. It’s dry but in a sort of interesting way in that although it lacks the sense of adventure of the series, Blish did a nice job of fleshing out the crew’s responsibilities in a way the show never had time for.

The funny thing is that there’s this one paragraph in which Kirk muses over human women’s interest in Spock that Kirk basically compares to jungle fever (I think the book was written in 1971?). It’s literally just like one paragraph and at the time was regarded as progressive, but every time I see retrospectives of this book now people fixate on it. Sometimes it’s the ONLY thing about the book they want to talk about and of course Blish gets nailed for racism.

The cover artist for KINSMEN OF THE DRAGON is Hannes Bok, for those keeping score at home. He was huge during that era. Got his big break from A. Merritt at The Atlantic Weekly.

All of you should track down a copy of Blish’s _Cities In Flight_, a fixup collection of four short novels in what’s called his “Okie” series. They’re about Earth cities flying around the Galaxy looking for work. The first one, kind of an “origin story” for the others, is slow, but the three set aboard space-faring New York are absolutely splendid.

Bonus points for explicitly using Oswald Spengler as his muse for these stories.

If Blish were indeed “right wing,” he kept some strange company. He was a member in the 1940s of the Vanguard Amateur Press Association, a Communist-leaning (“the Party is the vanguard of the proletariat”) apa. He also published an incredibly obtuse and conniving review of Clark Ashton Smith, “Eblis in Bakelite,” that is such a hit piece that I suspect if Blish were alive today he would be writing for SALON or MOTHER JONES.

For what’s it’s worth, both Blish and Knight dabbled in the Fortean borderlands of fantasy and sf.

Blish’s Jack of Eagles played with Fortean notions. I’m not sure how seriously Blish took Fort. The novel seemed an attack on van Vogtian plots. (It also used some time theories of J. W. Dunne — extensively mined by H. Beam Piper for the Paratime stories.) Knight wrote a biography of Fort.

I suspect Blish may have been one of those that thought styles of literature should always be evolving and that sf should embrace the newest trend: modernism.

But, as someone once said, experiments in art, like in experiments in evolution, usually fail.

I still plan to sample his fiction at some point, since it seems to be unusual if nothing else. His tastes and his remarks about prose style don’t inspire confidence, though…

One of the reasons you might write criticism is to play with

over-statement, so you might actually take some snide remarks by

“Athleling” with a grain-of-salt. I remember Athleling also

commenting on how in the good old days writers were more creative

about what “rays” could do (I don’t know what he made of Thorne

Smith’s “Night Life of the Gods”…).

I would say the trouble with the Athleling material is that it’s

a self-conscious attempt at “raising the standards” of the field

but often it’s just an effort at importing the values of the

academic literary world, without necessarily thinking very hard

about what Science Fiction is actually good at doing that might

be different from standard Literature. (In particular, the very

common foreground/background inversion often seems to have

escaped Blish in his commentary.)

I gather that many people commenting here are unfamiliar with Blish’s

SF, which is actually well worth reading– the Star Trek work was

near the end of his life, when I suspect he knew he was dying of cancer.

I’d recommend starting with the “Cities in Flight” collection,

which centers on a particularly dream-like image that I think has

now wedged itself in our consciousness (it recurs in places like

“Macross 7”, for example).

The book “Jack of Eagles” that someone else mentioned is also a

pretty interesting one. It tries to take psychic powers

mumbo-jumbo and ground it in physical reality (it’s one of the

few SF books I remember that uses equations in the text… Poul

Anderson’s “Tau Zero” is the only other one).

“The Quincunx of Time” is strange one that has some subtle

heaviness to it that I like quite a bit.

Oh: James Joyce. I think you need to hear “Finnegan’s Wake” read

aloud in a thick irish accent. It’s essentially “blarney”–

a massive pile of over-intellectualized humor.

(I find a better litmus test is Delany’s “Dhalgren”. If you

don’t like Dhalgren, that’s okay, but if you can’t grok that it

was phenomenally successful, then you’ve got problems.)