On an Earth far enough in the future to be depopulated and recolonized by the survivors from other worlds, nine castles are the sum total of civilization. Through technological marvels and a hierarchy of subordinate slave species, humanity rules its home world as feudal lords. Occasionally, the younger men would break from the unceasing pageantry of the castles to adventure among the Nomads, the indigenous survivors of Earth’s fall. This decadence is borne on the backs of the Meks, a humanoid species from another world who builds and maintains the technologies that fuel the castles’ war and pleasure machines.

On an Earth far enough in the future to be depopulated and recolonized by the survivors from other worlds, nine castles are the sum total of civilization. Through technological marvels and a hierarchy of subordinate slave species, humanity rules its home world as feudal lords. Occasionally, the younger men would break from the unceasing pageantry of the castles to adventure among the Nomads, the indigenous survivors of Earth’s fall. This decadence is borne on the backs of the Meks, a humanoid species from another world who builds and maintains the technologies that fuel the castles’ war and pleasure machines.

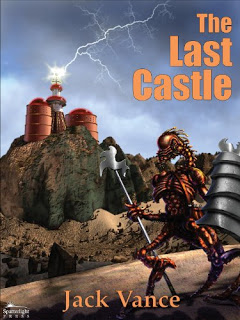

One day, the Meks vanish. All of them, leaving the castles bereft of the technological support needed for civilization. The castles limp along, until their slaves return and besiege the castles. One by one, the citadels fall until only Castle Hagedorn remains. Finally, the Meks levy their full might against the surviving remnant of civilization.

In The Last Castle, Jack Vance poses two conflicts. The action conflict is simple: can Castle Hagedorn survive the siege? However, it is clear from the eight fallen citadels that the existing social order cannot win against the Meks. So the more important conflict is whether necessity will drive the humans to radically reorder their society or if the inertia of tradition will rule. And even if necessity wins, it might be too little too late to ensure the castle’s survival.

The answer, of course, is for humanity to give up its slave races and abandon the castle, trapping the Meks inside. With the besiegers now the besieged, humanity’s survival is assured. The Last Castle, with its aristocratic decadence, still falls, and every man now lives by the sweat of his own brow.

The characters are stock, but the worldbuilding shines. From the various slave races to naming conventions to the Nomad tribes, Vance brings to life a strange future Earth full of wonders. The setting enlivens the formula of a last stand forcing social change; one that will reappear in The Miracle Workers.

I am forced to admit that I struggle to read Vance. I have repeatedly tried to start The Dragon Masters and others of his stories only to bounce off them. This is not because the quality of Vance’s writing is poor. Rather, like Gene Wolfe or John Wright, the writing is erudite and requires a closer read than normal. In the case of The Dragon Masters, the introduction of a sacredote in his cell required a fair bit of concentration to fully appreciate, often more than I can bring to the work in these busier days. But the adventure of a last stand made The Last Castle accessible from the first page. And while Vance is best known for The Dying Earth, I recommend reading The Last Castle as a way to ease into his strange and vivid worlds.

“the worldbuilding shines” – I read that book many years ago, but I think that is why it was rather panned. Why do you need such a complex world for a story this short? There was even a pedigree chart included, wasn’t there? I remember I liked reading it but it indeed makes you want to read more. A prequel maybe? Writers usually tend to exploit the worlds they create to the full extent. At least that is what we are used to.

The Lyonesse books are a good introduction to Vance as they are set on Earth in the relatively recent past, the Dark Ages, but are still full of magic and wonders. They show the same style and wit as his other works.

Vance did exploit some of his worlds, or more accurately he planned them as series, and he did revisit the Dying Earth eventually, for which we can be thankful.

Thanks for the review; you’ve made me want to read it, but I’ll have to buy it first.

Vance’s “Planet of Adventure” series and “The Five Gold Bands” may be his easiest reads. Lyonesse is pretty tough, especially the second one.