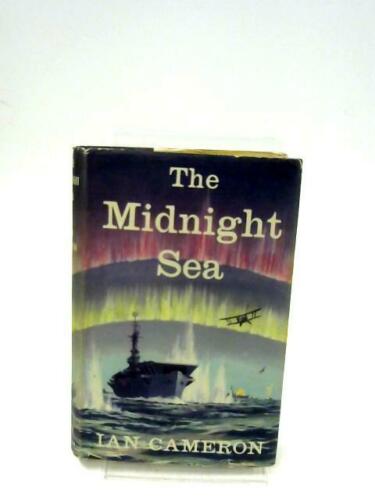

THE MIDNIGHT SEA by Ian Cameron

THE MIDNIGHT SEA by Ian Cameron

Reviewed by Richard Toogood

THE MIDNIGHT SEA opens, evocatively, on the bleak snow swept runway of Benbecula aerodrome in the Outer Hebrides. It closes upon an ebbing tide of the Kola Inlet. And dividing the two are twelve tumultuous days occupied with what Sir Winston Churchill described as “the worst journey in the world”: an Arctic convoy to Soviet Russia in the depths of the winter of 1944.

The book was the first published novel of the reticent English writer Donald Gordon Payne (1924-2018). It drew heavily upon his own wartime experiences as a pilot in the Fleet Air Arm where he flew the Fairey Swordfish on both Atlantic and Arctic convoys.

The book paints no sentimental portrait of this primitive machine which harkened back to the days of the Red Baron. Of flimsy construction and unarmed the Swordfish was cannon fodder for the likes of the Junkers-88. Its feeble Pegasus engine was also a precarious commodity to stake one’s life on in adverse conditions. This is brought home in one particularly poignant episode in the book when a returning patrol finds itself unable to make headway against a prevailing wind and simply runs out of fuel before it can catch up with the convoy, consigning its crew to a ghastly death. And yet for all its faults and fragility it performed a critical service in reconnaissance for convoys running the gauntlet of the German wolfpacks.

The complement of fifteen Swordfish and eight Wildcat fighters of the British aircraft-carrier HMS Viper is the chief focus of THE MIDNIGHT SEA. It bonds together two otherwise estranged characters: Captain Hugh Jardine and his son who, as the carrier’s only qualified batsman, has the grueling responsibility of landing every returning aircraft upon the often wildly pitching flight deck. As conditions deteriorate and the danger increases their respective duties come to exact a terrible physical toll upon both men.

Payne was far from being alone in possessing the credentials necessary to write such an authentic story of the Arctic campaign. The celebrated Alistair Maclean launched his own literary career at around the same time with the similarly inspired HMS ULYSSES. But the voice of experience is incoherent without a born writer’s gifts to lend authority to its words. And the book profits greatly from Payne’s efficient understated style that can still deliver a descriptive flourish when appropriate. Such as when a salvo from the German heavy cruiser Brandenberg is said to result in columns of water hanging, poised “like phantoms draped in transparent veils of spray”.

The tension begins to ratchet incrementally as Jardine marshals his small defensive screen of destroyers, corvettes and aircraft against a German armada of cruisers, U-Boats and land-based bombers. And if these fabricated foes do prove less daunting and rather shorter on resolve, courage and deadly efficiency than the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe were in actuality then it must be borne in mind that the book was published in 1958 when memories of the war were fresh, and its wounds still raw, and no one was overly bothered in massaging the ego of a beaten enemy.

There is no such artistic latitude to be found in the book’s description of the Arctic elements. These are written of with appropriate awe and respect. Never more so than when the convoy sails into a ferocious storm which convulses the sea into mountainous peaks and cavernous troughs of freezing water. Under such conditions even a 16-000-ton aircraft-carrier is relegated to the status of a child’s bath-time toy. But running in counterpoint to this are snapshots of serene beauty: the eddying flicker of the aurora borealis, the fleeting scuttle of a blood-red sun along a black horizon, the ominous dancing spirals of sea-smoke. The savage majesty of the nature of the north in all its tempers.

Payne would shortly afterwards bring his keen eye and descriptive powers to bear on the opposite extremity of the Australian Outback. His novel THE CHILDREN, written under the alternative alias of James Vance Marshall, was the source for Nicolas Roeg’s celebrated film Walkabout.

It is certainly possible to make the case that, in the long run, few operations damaged the German war effort more grievously than the Arctic convoys. Because as Napoleon had discovered over a century earlier with his ‘Spanish ulcer’ of the Peninsular War, the terrible attrition of the second Russian front consumed vast quantities of the Wehrmacht’s manpower and equipment to calamitous consequence. And sustaining that front was the business of the convoys. The price the Germans extracted from them for doing so was very heavy. Between 1941 and 1945 more than a hundred merchant vessels were sunk along with twenty warships. The cost in allied lives was in excess of 2700.

For many years British veterans of the convoys believed their war service to be a forgotten one. No campaign medal recognized their sacrifices because it was not considered politically expedient to acknowledge the aid afforded to a wartime ally who had since become a peacetime foe. To their credit the grateful Russians never shared this mulish attitude and were more than willing to bestow their own decorations on veterans of all nationalities. It was not until 2012, more than seventy years after the campaign had begun, that the British government finally sanctioned the striking of the Arctic Star.

But no medal can ever be anything more than a mute lump of medal. It can tell no one anything about the incredible fortitude and courage of a generation of men who endured appalling hardships in the service of a crucial cause. Who fought a war in the most unforgiving of all theatres and paid a grievous price in the purchase of victory.

A medal can convey nothing of this. But THE MIDNIGHT SUN does, and anyone with an interest in this neglected campaign will find it well worth their while in hunting down a copy.

Dedicated to the memory of John Hall AB, and all the crew of HMS Goodall. The last British warship to be lost in the western theatre of WW2: 29 April 1945.

A fine review! Good to see Mr. Toogood at the CH Blog.

‘But no medal can ever be anything more than a mute lump of medal. It can tell no one anything about the incredible fortitude and courage of a generation of men who endured appalling hardships in the service of a crucial cause. Who fought a war in the most unforgiving of all theatres and paid a grievous price in the purchase of victory.’

Indeed.