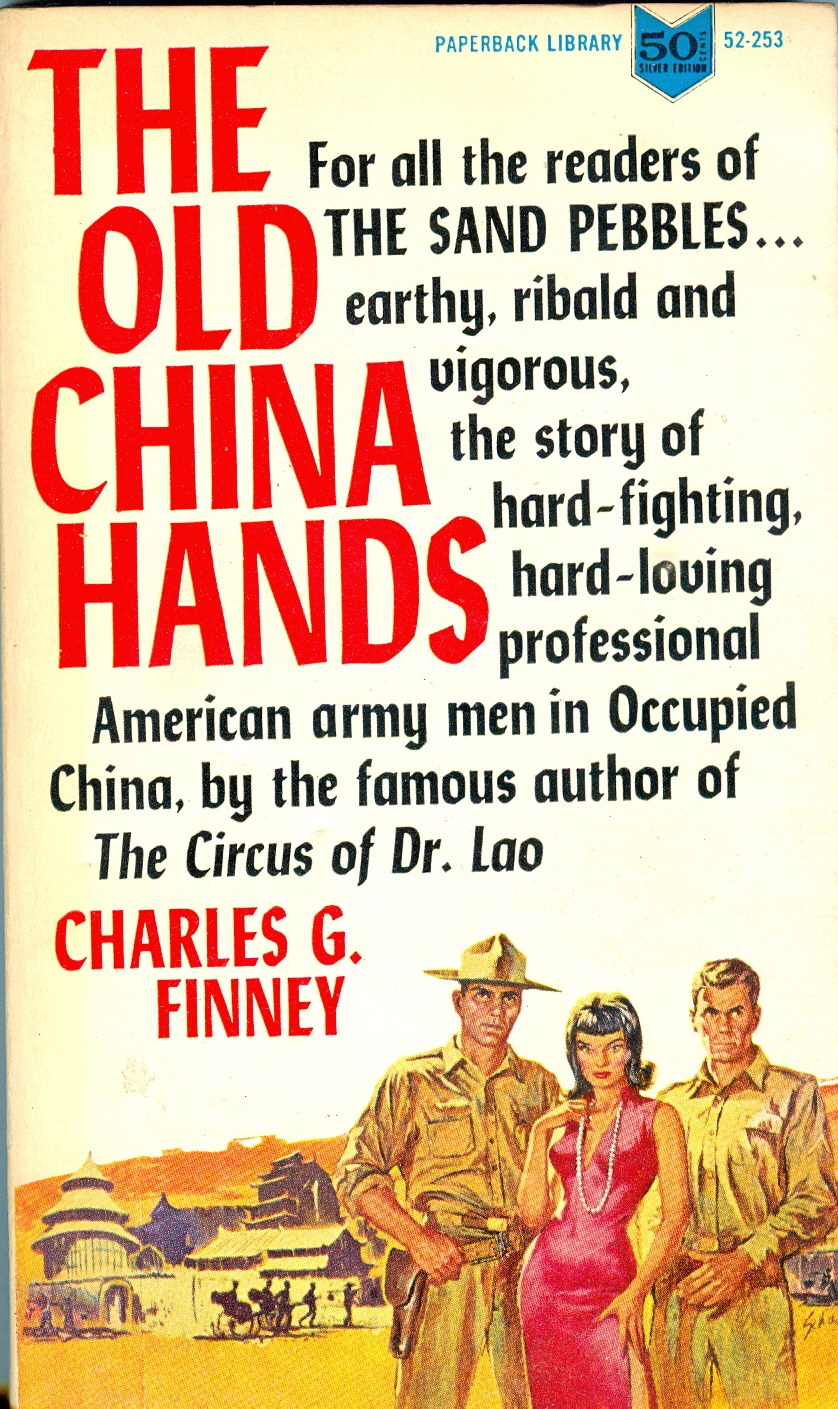

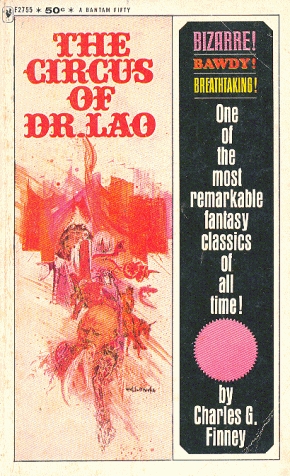

The Old China Hands by Charles G. Finney. I picked up this paperback probably 5 or 6 years ago at Windy City Pulp & Paperback Show. Finney (1905-1984) is best known for writing The Circus of Dr. Lao (1935). You may have seen the 1963 movie with Tony Randall and Barbara Eden. The novel was a huge influence on Ray Bradbury.

The Old China Hands by Charles G. Finney. I picked up this paperback probably 5 or 6 years ago at Windy City Pulp & Paperback Show. Finney (1905-1984) is best known for writing The Circus of Dr. Lao (1935). You may have seen the 1963 movie with Tony Randall and Barbara Eden. The novel was a huge influence on Ray Bradbury.

Finney served in the U.S. Army with the 15th Regiment, which was stationed in Tientsin, China from 1912-1938. The 15th Infantry Regiment was sent to Tientsin during the Chinese Revolution. It’s job was keep the road open to Peking so there would be no repeat of the siege of the foreign legations as happened in the Boxer Rebellion. There were also British, French, Italian Marines, and Japanese military contingents in Tientsin.

This book was published in hardback in 1961. The success of Richard McKenna’s The Sand Pebbles spurred a paperback reprint in 1963 for The Old China Hands. A few sections of this book appeared in The New Yorker in 1959 and 1960. The book is a series of episodes, almost vignettes of life in the Old Army in a foreign land.

There was déjà vu reading this novel as I thought of a passage from Brian McAllister Linn’s Guardians of Empire, a book about the U.S. Army in Hawaii and Philippines.

“They were a lean sharp lot – their canvas gaiters scrubbed white, fitted over brilliantly shined shoes without a wrinkle, their uniforms made by Chinese tailors, at their expense, fitted their trim athletic bodies and bore no relation to the ill-shaped travesties of uniforms then issued to stateside garrisons. They could shoot well. Their drill was precise.”

Finney describes life in an exotic location. The 15th Infantry had Chinese houseboys to do laundry and shoeshines. The troops ate very well, went on long hikes, the shooting range. There were two battalions of the 15th in Tientsin. The first battalion was in Manila in the Philippines when Finney arrived. They kept a Chinese warlord’s army out of Tientsin in 1924. The warlord had a mounted unit of White Russians armed with Mauser pistols, lances, and da bao swords slung across their backs. They used the swords to decapitate enemy soldiers. The White Russians were wiped out a couple years later by the Chinese Nationalist troops of Chiang Kai-shek.

There were a number of foreign-born men in the 15th. One sergeant was a German who had served in the German Imperial Guard and won an Iron Cross in WW1.

“As did many of his German companions-in-arms, he left the Fatherland after its defeat and migrated to the United States. Soldiering was all he knew, and he joined the U.S. Army.” He refers to the 15th as “America’s Foreign Legion.”

Finney gives the impression that the Army guys just wanted quiet evenings to drink their beer. A brigade of Marines arrived (including pulp writer Arthur J. Burks) with Gen. Smedley Butler in command. The Marines were ready to slaughter all Chinese armies and raise hell. They got into a lot of fights. Finney did not seem to have a great opinion of the Marines.

Gen. Butler was not happy that the 15th Infantry had special drill rifles with highly polished stocks. He ordered the Marines to strip the varnish off their rifle stocks and polish them.

“A Springfield, of course, the most accurate and probably the comeliest military shoulder weapon ever devised.” Finney mentions men in the regiment who could hit targets at 600 yards. Growing up, there were a lot of old military veterans. They loved their Springfield ’03s.

There was a colony of retired Army guys in Tientsin they called “Old Fogies.” Finney also calls those with Chinese wives or concubines as “squaw men.”

Finney tones down the fightin’, drinkin’, and whorin’ in the book. There are flashes that these regulars could turn on a dime and get into a fight. A group took a trip to see the Great Wall of China on the Manchurian border. The train was running hours behind schedule and one soldier suggested busting up the train ticket office in retaliation.

The 15th was withdrawn from Tientsin in 1938 amidst growing fears of a clash with the encroaching Japanese. The 15th became part of the famed 3rd Infantry Division including Medal of Honor recipient Audie Murphy. George C. Marshall, later head of the U.S. Army in WW2 and Joe Stillwell are both mentioned. The 15th produced quite a few generals in fact. What is odd is a small contingent of the North China Marines replaced the 15th Infantry Regiment as caretakers of the barracks. The North China Marines in Peking, Tientsin, and Chingwangtao were forced to surrender on December 8, 1942 to the Japanese. A ship was on the way to evacuate them. A total of 203 marched into captivity. The State Department refused to evacuate them in time.

The U.S. Army may have been only 133,000 at the time but the men were hardcore and knew their business. Reading this book, there is a cultural resonance that intersects with much pulp fiction from the time.

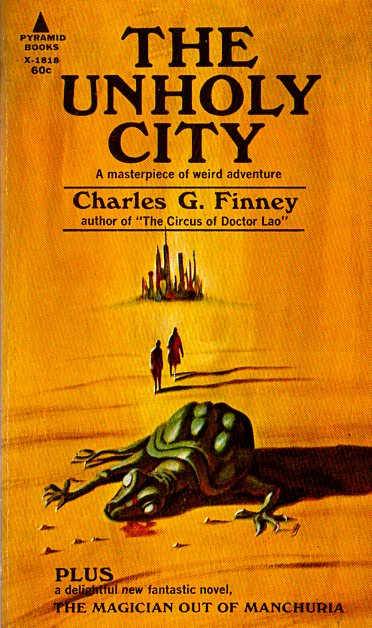

This post lead me into an interesting bit of bibliographic research. I already knew Finney’s name; I have copies of his novels “The Circus of Dr. Lao” and “The Magician Out of Manchuria”. So, I thought “The Old China Hands” would be worth reading if I could find a copy. I checked the catalog of my local library. Nothing at all by Finney. Then I went to Amazon. That is when things started to get strange. There were lots of titles by Charles G. Finney. However, almost all of them had titles like “How To Experience Revival”, “True Christianity” or “Holy Spirit Revivals”. WTH??

At first I thought it was just a confusing and annoying coincidence of names. Then I went to Wikipedia and discovered that Charles Grandison Finney (1792-1875) was a famous evangelist and a great-grandfather of Charles Grandison Finney the 20th Century author!

Curiously, there are many more books by Charles G. Finney the evangelist available than those of his great-grandson the fantasy author. I did find a Kindle edition of “The Circus of Dr. Lao” available at $14.95 (which I think is rather steep). As for “The Old China Hands” the least expensive paperback edition I could find was at $39.99.

I hope you paid less for yours.

I encounter a similar problem with Edward Frankland, a superb and now woefully neglected historical novelist. Book searches are invariably muddied by reams of material relating to his grandfather (after whom he was named) who happened to be an eminent Victorian chemist.