Sword & sorcery as a fictional genre had its origin in the weird fiction pulp magazines of the late 1920s into the 1930s. There was a forgotten variation in Planet Stories in the 1940s. Then it disappeared from the magazines for the most part in the 1950s.

There was a renascence in the digest magazines in the early 1960s. A new interest in Edgar Rice Burroughs and Doc Savage prompted first reprints of sword & planet fiction. Mass market paperbacks by Ralph Milne Farley and Otis Adelbert Kline and then new fiction from Gardner Fox and Michael Moorcock (as Edward Bradbury) brought swashbuckling with a sword back in fashion.

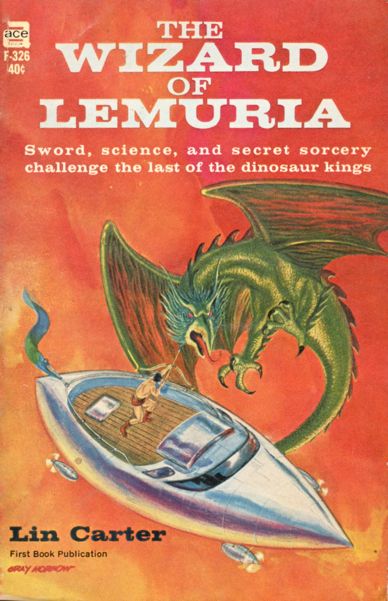

Sword & planet opened the door for sword & sorcery in a new format: the mass market paperback. The writer who was first was Lin Carter. The Wizard of Lemuria was the first sword & sorcery novel by a writer who did not start in the pulp magazines. The Wizard of Lemuria (Ace Books, 1965) was not Carter’s first novel, but it was the first to be published. Wizard introduced Thongor of Lemuria as the hero center stage and offered much of what readers would come to recognize as the Lin Carter style. Edgar Rice Burroughs was the most readily apparent influence on Lin Carter’s plotting and prose in this and subsequent books.

Carter’s Lemuria combined elements of Burroughs’ Barsoom and Pellucidar, only a Robert E. Howard-style barbarian stalked across the resulting continent. Thongor is probably Carter’s best-known character, larger than life and more heroic than most he would create. Carter describes Thongor in this passage from The Wizard of Lemuria:

“A bronzed giant, naked save for leather clout and black cloak, standing atop the parapet, a longsword in his hand. Golden eyes blazed in a clean-shaven face, and a long, wild mane of black hair fell to the naked shoulders.” (p. 18)

Against a backdrop of the lost continent of Lemuria, located in an area now occupied by the Pacific Ocean 500,000 years ago, Thongor, a mercenary from the wintry northland of Valkarth, kills a superior officer in a duel over an unpaid wager. Imprisoned, he escapes through the aid of a friend and steals a prototype airship. The craft is attacked by a giant “lizard-hawk” and, damaged, subsequently crashes into the jungle. Sharajsha, a wizard with uses for a swordsman of Thongor’s prowess, aids the barbarian and repairs the airship. He means to enlist Thongor on a quest to defeat a conspiracy by a remnant of the Dragon Kings. The Dragon Kings once ruled all of Lemuria millennia before and plan to retake the continent from humankind when the stars are right. Along the way, Sharajsha and Thongor steal a star stone in order to forge the Sword of Nemedis, a weapon that acts as a talisman of power against the Dragon Kings. There are various adventures including rescuing the captive Princess Sumia. Thongor is a man of action:

“Therefore, he sprang, taking the spearmen off guard. From complete immobility he flashed into action. Whirling on his heel, he leaped at the first spearman, felling him with a straight-armed blow to the jaw and wrenching the long spear from his slack hands. Whirling again, he charged at the dais. A guard interposed, but Thongor ran him through the belly and the man fell, clutching with numb hands at this tumbling guts. In a flash he was up the marble steps Drugunda Thal was rising to his feet, features working with terror. Thongor swung the steel base of the spear at his head, knocking the Sark sprawling.” (p. 59)

Thongor destroys the Dragon Kings with the magic sword, which becomes an energy weapon when activated. This was a plot Carter would repeat- a rugged adventurer falling into a quest with a older mentor/wizard/scientist who provides arcane knowledge to foil a conspiracy to conquer the world (or galaxy). A beautiful princess or slave girl is generally saved along the way; sometimes an evil femme fatale is part of the story to tempt the hero. Providential divine or semi-divine intervention is required to defeat the villain at the novel’s climax. Carter was fond of using magic weapons, talismans, and amulets, many of which resemble what The Encyclopedia of Fantasy terms “plot coupons.”

His heroes rarely thwart the conspiracy by their own strength or intelligence. Intervention by a higher power saves the day again and again, but also detracts from the heroism that is of course a hero’s reasonfor being.

The Wizard of Lemuria did not meet with approval in all quarters. A review in Amra V2 #36 (Sept. 1965) by Archie Mercer stated,

“The only such distinguishing feature I am able to discern in The Wizard of Lemuria is that it is entirely derivative of other works in the genre, with no obvious originality whatsoever.”

In the same issue of Amra, Harry Harrison said :

“He has done such an incompetent job that for a few moments there I though he was writing a parody of swordplay-and-sorcery…Why does this book offend me? Because there is not an ounce of originality in it. The people, machines, names—everything has been assembled out of an old box of Burroughs and Howard fragments.”

Harrison went on show some examples of inconsistencies and summed it up at the end with:

“Am I being cruel? Perhaps. But Lin Carter was cruel to me. He promised me an ‘action packed novel’ with ‘vivid sword-and-sorcery impact’ and he did not deliver. I read his book and I was not satisfied. I wish he would go away and think about what I have said, then sit down and try to write a more consistent and interesting book of his own.”

Neither abashed nor deterred, Carter followed in 1966 with Thongor of Lemuria published by Ace Books. Thongor of Lemuria was a direct sequel to The Wizard of Lemuria and continued the adventures of Thongor on the path to empire and more sequels. Both had covers painted by Gray Morrow.

Neither abashed nor deterred, Carter followed in 1966 with Thongor of Lemuria published by Ace Books. Thongor of Lemuria was a direct sequel to The Wizard of Lemuria and continued the adventures of Thongor on the path to empire and more sequels. Both had covers painted by Gray Morrow.

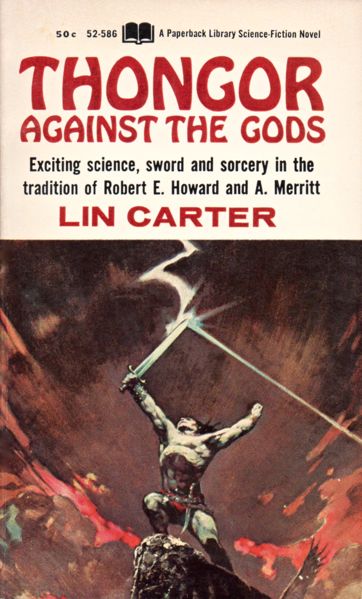

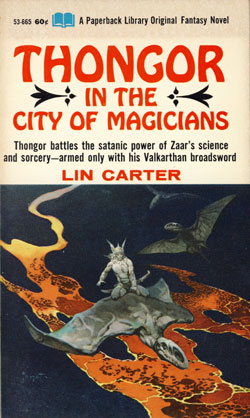

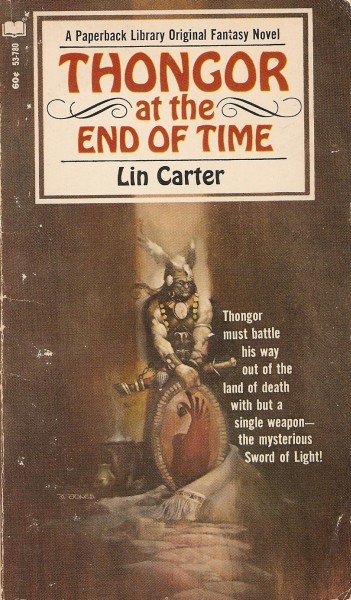

Carter would switch Thongor to Paperback Library with Thongor Against the Gods in 1967 and Thongor in the City of Magicians in 1968. He had the luck of covers painted by Frank Frazetta. Both covers are classic Frazetta and iconic. Thongor at the End of Time (Paperback Library, 1968) would have a cover by the up and coming Jeff Jones.

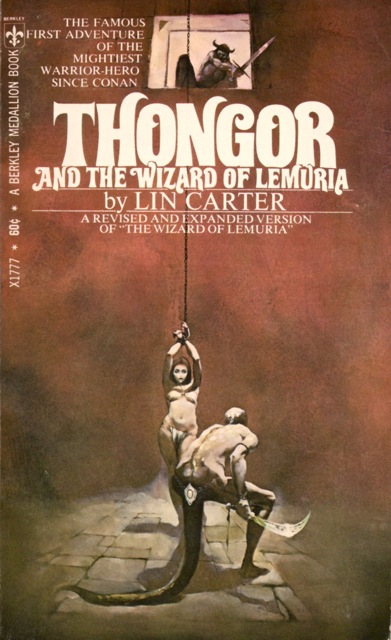

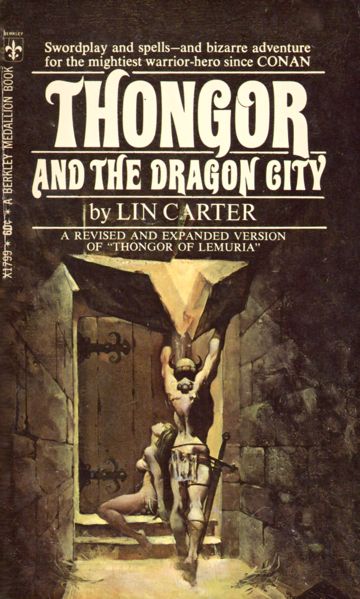

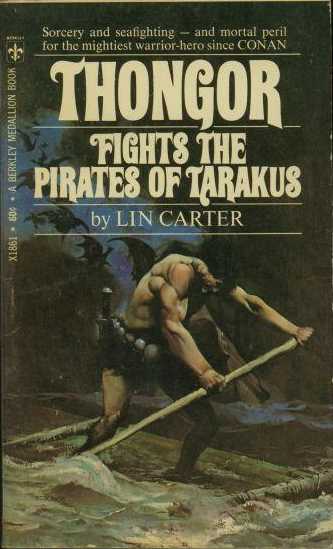

Carter would change publishers again. He expanded the first two Thongor novels with the title change of Thongor and the Wizard of Lemuria (1969) and Thongor and the Dragon City (1969) with Jeff Jones covers. The last Thongor novel, Thongor Fights the Pirates of Tarakus in 1970 again with a cover by Jeff Jones. None of the Jones covers look specific to Thongor. They could be used on any generic sword & sorcery novel. Warner Books and Berkley both reprinted the Thongor novels in the late 1970s during the sword-and-sorcery boom of that time.

The advent of original sword & sorcery anthologies gave Lin Carter an opportunity to write some shorter stories about Thongor. He went back to events before The Wizard of Lemuria to write two stories with a markedly reduced Edgar Rice Burroughs influence for anthologies edited by Hans Stefan Santesson. “Thieves of Zangabal” (The Mighty Barbarians, Lancer Books 1969) owes its plot to Robert E. Howard’s “Rogues in the House.” A priest hires Thongor to steal the magic mirror of Athmar Phong, a mighty sorcerer. Thongor battles a demon and manages to kill Athmar Phong, rescuing his new friend Ald Turmis in the process. “Keeper of the Emerald Flame” (The Mighty Swordsmen, Lancer Books 1970) had Carter recycling some elements used originally in “The Thing in the Crypt.” Thongor and his bandits find a lost city in the jungles of Lemuria. His men are killed one by one at night and he discovers an animated mummy of a once powerful wizard performing the crime. These stories are set on a small scale in comparison to the novels for Thongor. Carter had a tendency to overwrite and draw out his shorter Thongor stories during the final climax. Both of these stories could have been cut and not lost anything in the telling. Less would have been more in this situation.

Four more Thongor stories would appear in the Ted White era Fantastic Stories and The Year’s Best Fantasy from 1974 to 1980. Those stories have almost no Edgar Rice Burroughs influence and veer more to the Robert E. Howard side.

Carter attempted to bridge the gap between Burroughsian sword-and-planet and Howardian sword-and-sorcery by combining barbarian swordsmen with pseudo-science with a dash of Lovecraftian supernatural menace thrown in. Write a short novel in a pulp style derived from Edgar Rice Burroughs with some Dunsanian word flourishes and that was Carter’s style. If the fiction was a short story or novelette, it was a monster story that would not be out of place in a comic book.

He got to the paperbacks first.

Please give us your valuable comment