The Pulpish Master: Rafael Sabatini

Saturday , 26, August 2017 Authors, Before the Big Three 9 Comments

It’s practically impossible to find a picture of Sabatini without a suit and tie, including one where he was fishing!

When I mention bold fighting heroes laughing at death and their enemies, odious and powerful villains, non-stop action and adventure in picturesque settings, and brave, beautiful, worthy women, what writer comes to mind? For most readers of this blog, it would be Robert E. Howard. But another name fits equally well, that of the great Rafael Sabatini. Around the same time that Howard was writing his pulp fantasies, Sabatini was producing historical fiction with a very similar aesthetic. The settings are different, but there is a good deal of similarity in their adventures. In fact, given how well-read Howard was, I wouldn’t be surprised if he was very familiar with Sabatini’s work, which first became popular in the 1910s.

In some cases, a writer’s life has seemingly little influence on what or how they write. In Sabatini’s case, however, it explains a lot.

Born to an English mother and an Italian father in 1875, Sabatini lived all over Europe and spoke five languages before he learned English. However, he chose to live in England from the age of 17 to his death in 1950 and wrote exclusively in that tongue, since “all the best stories are written in English”. And indeed, there is a very powerful love and appreciation of English history and culture in Sabatini’s writing. It goes even further, however, as Sabatini’s protagonists frequently embody the best of the English character. Honorable, brave, intelligent, and tough, facing even the most hopeless and deadly situation with grim determination and a joke on their lips. It should be noted, however, that Sabatini’s Anglophilia never goes overboard. Not only are there numerous distinctly English villains of the worst variety, but oftentimes even the institutions of government are shown to be wholly corrupt, as in Captain Blood, discussed further below.

And yet, Sabatini is very different from the English adventure writers of the period, like a Sir Anthony Hope. (The Prisoner of Zenda). Nowhere in his stories does one find the temperance or moderation of the English protagonist. On the contrary, there is volcanic passion and anger! And frequently a deep, thirsting desire for revenge. Despite their honorable natures, Sabatini’s heroes can be very cruel indeed towards their enemies. In this we likely see influence from Sabatini’s Italian half.

Lastly, Sabatini’s parents were both opera singers. And in their son’s stories, there is a very strong theatrical element. The witty rejoinders, the buffoonish comedic relief, and the violent emotional reactions would be perfect on a stage. On that last point, Sabatini accomplishes a singularly difficult task. He deftly avoids melodrama or what I call emotional melisma; the feelings are tremendous, but never over-embellished, out of proportion to what is occurring, or overly fixated upon. I despise melodrama, but can connect to the emotions of Sabatini’s protagonists. In particular, that’s because the dominant force in his stories is one of revenge

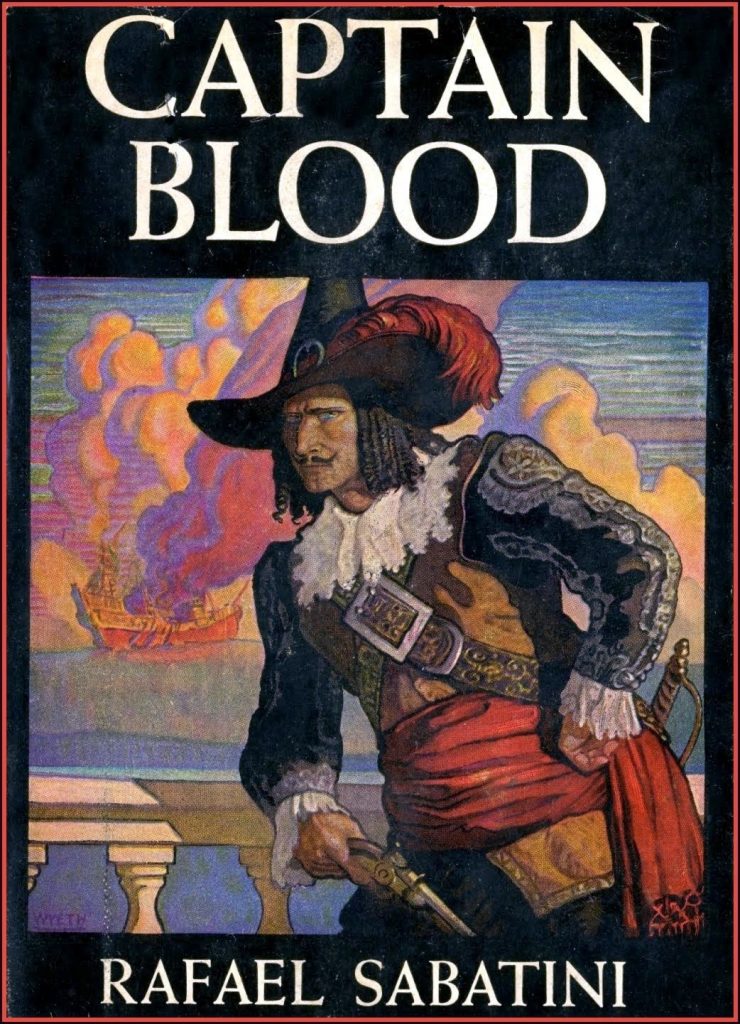

A fine N.C. Wyeth cover.

Sabatini wrote extensively over the course of his life, but without question his two greatest masterpieces are the aforementioned Captain Blood and Scaramouche. In the former, an Irish surgeon scorns an uprising against the English in the late 1600s but yields to his duties as a doctor to treat the wounded. Unfortunately, he is captured and sentenced to slave labor in the Caribbean by the courts, where Blood escapes his cruel master and embraces a new career, that of pirate. The ensuing battles and schemes, with enemies all around Blood, with only his courage, wits, and strength to save him, is as worthy a pulp adventure as one will find. It is notable, too, that despite being a fearsome corsair, Blood still preserves the dignity and honor of a gentleman, never resorting to wanton murder, rape, or any sinful, degrading behavior. Thus, not only is there the same high adventure in exotic, imaginative settings, but the book maintains a moral core, a feature central to the best pulps. And like a Conan, Blood is not above cruelly mocking and humiliating his enemies when he has them right where he wants them.

Scaramouche is uncharacteristic for Sabatini in being a wholly French tale, set during the time of the French Revolution. The epic begins with one of the best opening lines I have come across;

He was born with a gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad.

Thus we are introduced to Andre-Louis Moreau, a young man studying to be a lawyer. He is intellectually brilliant and wickedly funny, never taking anything too seriously, and frequently mocking his friend Philippe de Vilmorin for idealistically advancing the revolutionary cause. But as with Blood, all that changes one fateful day, when his friend Vilmorin, protesting the execution of a peasant for poaching on orders of the Marquis de la Tour d’Azyr, is goaded into a duel by the Marquis. Vilmorin barely knows how to handle a sword, while his opponent is one of the finest swordsmen in all of France. It ends in Vilmorin’s slaughter.

From that moment on, Moreau, a poor, scrawny bastard, holding his dead, blood-spattered friend in his arms, vows revenge on the powerful Marquis. And what follows is a magnificent adventure that spans the gamut of France on the eve of the Revolution, with Moreau and Marquis both keenly involved in its events. As befitting a Scaramouche of the stage, Moreau is constantly changing his profession, being at times a politician, a playwright and actor, and a swordsman. Every skill of which he uses against his nemesis, the Marquis, gradually becoming what the nobleman laments as the “evil genius of my life”. The whole book is thrilling from beginning to end, with exceptional variety. The part on the history of the French comedic theater is almost as exciting as the superbly described duels to the death. There is a distinct zest and passion through it all, ending in a perfect climax.

While not considered a pulp writer, I doubt anyone will begrudge me calling Sabatini a pulpish master. His stories bear the same heroism, moral core, intelligence, action, and manliness as the best pulps. I highly encourage the readers of this blog to discover his wonderful tales for themselves.

Anything by Sabatini is worth a look, but if you like swashbuckling adventure, you need to read Scaramouche and either Captain Blood or the Sea Hawk. I think your title of Pulpish Master fits him to a T.

Omni Omnibus!

It is worth noting that Sabatini also wrote two collections of short stories starring Captain Blood: “Captain Blood Returns” (aka “The Chronicles of Captain Blood”) and “The Fortunes of Captain Blood”.

I do think “Scaramouche” is one of the great romantic novels and for anyone who has not read it my earnest advice is: get yourself a copy soonest. It is a splendid read.

Right on! I consider Sabatini the greatest writer of the “pure” swashbuckler. Besides writing great action, he was also very adept at crafting quotable lines. REH was a fan.

Sabatini was absolutely a pulp writer, appearing alongside Sax Rohmer in UK pulps like Premier Magazine:

http://www.sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/premier_magazine

He was also published alongside Mundy, Haggard and Harold Lamb in the legendary pulp, Adventure. Sabatini achieved more mainstream success and acclaim in the 1920s, but his roots were in the pulps.

Wasn’t a movie done of Capitain Blood with Errol Flynn?

I’ve heard f him but wasn’t aware he was the authour.

As for the passoon, I wonder if we wasn’t happily playing along with the stereotype of the time. Not to diminish his sincere passion but I wonde.

Was his mom recusant? Just curious as it might provide some additional layers.

xaviee

-

Yes, the movie is a classic and quite faithful to the book. As I recall, the movie combines a couple of the female characters and tightens up the plot to fit within a normal movie run-time, which are reasonable changes, I think, and it’s somewhat vague about why Blood is sentenced to slavery, presumably to avoid offending parts of the audience (in the book, Blood is a Catholic who helps a wounded Protestant during the Monmouth Rebellion and since the Catholics win, he’s named a traitor. The movie just reduces it some unspecified civil war with no named denominations).

Sabatini ia a master, props on giving his props! Along those same lines, see also:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emilio_Salgari his, Black Corsair is a classic. See also:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Year_of_the_Horsetails

Though both books are Historical Fiction, both could, with mild tweaking, be Fantasy Classcs!

Sabatini is in my mind THE great writer of historical fiction. Dumas’ tales were good, but overlong and devoid of the level of passion and color Sabatini could inject; and Stevenson (who was undoubtedly a better stylist) did not write prolifically enough to match him; while I think that Hope and Orczy had lucky hits they could not quite reproduce. Meanwhile, there are no “bad” or even “mediocre” Sabatini novels. Captain Blood and Scaramouche stand a head taller than the others, perhaps, more by virtue of their size and density, but The Trampling of the Lilies (another French Revolution story), The Shame of Motley ( a renaissance tale in which the protagonist is a court jester) and The Strolling Saint (which is not an adventure at all, but a slow-paced and brilliant social commentary and character study) are all great works in their own right. And that is without mentioning all his other equally rollicking novels and his output of great short fiction (I’d particularly recommend his Casanova stories).

Many of his works, including Captain Blood, are available on Project Gutenburg. Everyone here who wants to write should check them out. Sabatini may have had his roots in the pulps, but in my mind he transcended them, not as a brilliant pulp-writer as a brilliant writer PERIOD.