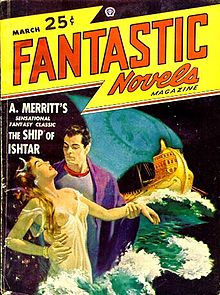

The divide between what readers are supposed to like and what they actually like can be no clearer than it is in the career of A. Merritt. The most popular story of all time according to the readers of Wonder Stories magazine back before the Campbellian Revolution had fundamentally transformed science fiction? The Moon Pool by A. Merrit. The most popular story that Weird Tales published in its heyday? The Woman of the Wood by A. Merritt. The story selected as the readers’ favorite out of fifty-eight years of Argosy magazine? The Ship of Ishtar… by A. Merritt.

The divide between what readers are supposed to like and what they actually like can be no clearer than it is in the career of A. Merritt. The most popular story of all time according to the readers of Wonder Stories magazine back before the Campbellian Revolution had fundamentally transformed science fiction? The Moon Pool by A. Merrit. The most popular story that Weird Tales published in its heyday? The Woman of the Wood by A. Merritt. The story selected as the readers’ favorite out of fifty-eight years of Argosy magazine? The Ship of Ishtar… by A. Merritt.

The man was simply a giant among giants. And he stood head shoulders above popular authors even outside of his genre. A lot of us keep saying that fantasy and science fiction went downhill once Star Wars and Shannara made such a big splash. A lot of us take it for granted that fantasy was this tiny scene dominated by weirdos and misfits up until then. But it wasn’t always that case. Sure, people take it for granted that you can just extrapolate backwards from someone else’s second hand accounts of what things were like in the sixties. But history won’t cooperate. Fantasy and science fiction was tremendously popular in the twenties and thirties. It’s what people people wanted to read!

How then could a guy that held the title Lord of Fantasy lapse into outright obscurity…? Well, it was not due to his successors besting him on the basis of raw quality. A. Merritt was actively erased from science fiction as if he were some sort of literary Trotsky. A clique redefined the genre specifically to exclude the sort of scientific romances that established it in the first place. The weirdos gradually took over. And science fiction suffered a well deserved loss appeal in the process. To add insult to injury, the opening stages of this debasement is referred to as “the Golden Age” even by people that would actually prefer the older stuff!

What was the key to A. Merritt’s success? Let’s take a look at the first part of The Ship of Ishtar and see what we find:

A tendril of the strange fragrance spiralled up from the great stone block. Kenton felt it caress his face like a coaxing hand.

He had been aware of that fragrance–an alien perfume, subtly troubling, evocative of fleeting unfamiliar images, of thought-wisps that were gone before the mind could grasp them–ever since he had unsheathed from its coverings the thing Forsyth, the old archaeologist, had sent him from the sand shrouds of ages-dead Babylon.

Once again his eyes measured the block–four feet long, a little more than that in height, a trifle less in width. A faded yellow, its centuries hung about it like a half visible garment. On one face only was there inscription, a dozen parallel lines of archaic cuneiform; carved there, if Forsyth were right in his deductions, in the reign of Sargon of Akkad, sixty centuries ago. The surface of the stone was scarred and pitted and the wedge-shaped symbols mutilated, half obliterated.

Notice he presents something weird or uncanny from the first sentence. The second introduces a note of beguiling allure. The third engages the senses while setting the action in the mundane present. The following paragraph then introduces an ancient artifact and ties it to an actual historical figure.

What an opening!

Following a brief jaunt into the unknown, Merritt feeds the reader just enough facts to keep them going:

The inscription might have given some clue had it not been so mutilated. In his letter Forsyth had pointed out that the name of Ishtar, Mother Goddess of the Babylonians–Goddess of Vengeance and Destruction as well –appeared over and over again; that plain too were the arrowed symbols of Nergal, God of the Babylonian Hades and Lord of the Dead; that the symbols of Nabu, the God of Wisdom, appeared many times. These three names had been almost the only legible words on the block. It was as though the acid of time which had etched out the other characters had been held back from them.

Kenton could read the cuneatic well nigh as readily as his native English. He recalled now that in the inscription Ishtar’s name had been coupled with her wrathful aspect rather than her softer ones, and that associated always with the symbols of Nabu had been the signs of warning, of danger.

Notice that he introduces real mythological figures as if they are true. Just as the author of Beowulf connects Grendel to the lineage of Cain and Edgar Rice Burroughs traces his Plant Men back to the Tree of Life, Merritt takes something legendary and writes what it would be like it if it were true.

But all of this is to set the stage for what really counts:

They slipped from the cabin. She ran to an inner door; dropped a bar across it.

She turned, back against it; then stepped slowly to Kenton. She stretched out slim fingers; with them touched his eyes, his mouth, his heart–as though to assure herself that he was real.

She cupped his hands in hers, and bowed, and set her brows against his wrists; the waves of her hair bathed them. At her touch desire ran through him, swift and flaming. Her hair was a silken net to which his heart flew, eager to be trapped.

He steadied himself; he drew his hands from hers; he braced himself against her lure.

She lifted her head; regarded him.

“What has the Lord Nabu to say to me?” her voice rocked Kenton with perilous sweetnesses, subtle provocations. “What is his word to me, messenger? Surely will I listen–for in his wisdom has not the Lord of Wisdom sent one to whom to listen ought not be–difficult?”

There was a flash of coquetry like the flirt of a roguish fan in the misty eyes turned for an instant to his.

Thrilling to her closeness, groping for some firm ground, Kenton sought for words to answer her.

Merritt wastes no time developing the sensuous romantic tension of the opening lines. By the end of the first section break, he not only leads the reader into an encounter with a goddess, but he has her flirting with the protagonist even as the suspense is developed.

I’m not sure how anyone could think it a good idea to change fantasy into something that isn’t really all this fantastic. But this… this is really something else. One thing is clear, though: Argosy’s readers had really good taste!

“Ishtar” was my introduction to Merritt and still barely edges out all his other novels in my book.

Back in the late ’50s, James Blish set the stage for the reading out of Merritt from the canon as a hack. Mike Resnick curbstomps Blish here:

Blish attacked many of the pulp stalwarts beloved by us here. You can check out a list of his reviews, which set an example for later cultural assassins, at his entry in the isfdb:

http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/ea.cgi?7

“weirdos and misfits”

That is one way to describe ***** **** **** * *** **** ********* *** *** **** * **** ****** **** **** ***** ***** ***** ****** * ** ***** *********** **** *** ****room or the closet, *** * ** **** **** ***** ** **** ** ***** graves

My wrath that burns brighter then a 1000 suns against this clique and the people in it aside this is very important:

“Sure, people take it for granted that you can just extrapolate backwards from someone else’s second hand accounts of what things were like in the sixties. But history won’t cooperate. Fantasy and science fiction was tremendously popular in the twenties and thirties. It’s what people people wanted to read!”

Weird Pulp was huge and its echoes are everywhere. Not the least of which can be found in what the “weirdos and misfits” made. Huge portions of which exist for the sole purpose of targeting and deconstructing those works that were built before them.

Pretty cool book available on amazon at

https://goo.gl/87ZkeT

A lot of the books you talk about are covered.

-

Yeah, that would pretty well cover it. I wonder what editions they’re using? Merritt, God bless ‘im, had a habit of revising texts, not always for the better. Also, editors would sometimes make him change story endings between the pulp appearance to hardcover editions; usually for a “happier” ending.

It would be great to see “authoritative” editions of all his novels. So far, that can only be said for THE METAL MONSTER and THE SHIP OF ISHTAR, in my opinion.

-

For example, Merritt’s preferred ending to Dwellers In the Mirage can be found only in the old Famous Fantastic Mysteries reprint magazine.

-

Exactly. Now, we could see ebooks/POD with the “best” versions. All it would take is the right editor(s). As I said, “Ishtar” and “Monster” are already out there in what I consider the “best” versions. I don’t think “Footprints” was ever significantly revised, so it would probably count (in my book).

-

-

A fantastic book by an author who should be better known. Maybe you can get him some of the acclaim that was denied him the past 30 years or so.

I’ll do my part: I’m going to Amazon and buy one of his novels as a gift. Then I’m going to strip every book by Blish from my library; they’re going to GoodWill before I lose my temper and burn them.

-

Sounds like a plan. Out of his numerous other targets, I recall Blish was also particularly savage to Clark Ashton Smith.

Damon Knight was a fellow traveler of Blish’s in many ways. He’s credited with bringing down AE van Vogt (who was a Merritt fan, BTW). Knight thought Robert E. Howard was entertaining trash.

http://robert-e-howard.org/SandRoughs13ss13.html

-

You’re just stoking the blood pressure now, deuce.

CAS AND REH? Knight is on the same list as Blish. Time I cleaned house.

-

There’s some hilarity to the fact that Blish is almost forgotten nowadays and that Damon Knight is certainly completely forgotten. Unlike CAS and REH. Amazon reviews for something like A Case of Conscience are also darkly fun in their own way, as it seems that latest generation of SF readers views Blish’s fiction as badly aged and overly religious. Wouldn’t be surprised if critics who followed in his footsteps view him in that same light.

-

Yep. Mike Resnick, who loves the “Bad” Old Stuff, predicted as much 20yrs ago:

Ah, the schadenfreude.

-

-