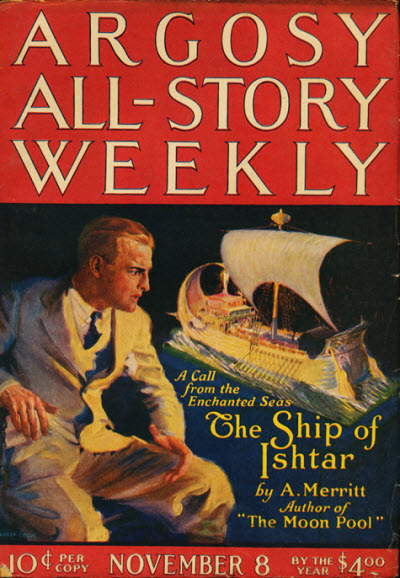

Walk through the aisles of any Barnes & Noble and you see the same cover concept over and over: a brilliantly dressed female hero, standing around… looking cool! It is the very antithesis of dynamism. Nothing is at stake. Nothing is happening. There is no danger. There is nothing to thrill or titillate. Decades ago, paperback covers would promise all manner of wonders and adventure. Today’s books offer little more than a mirror to an essentially effeminate audience. And judging a book by its cover really is a safe bet in this case. After all, how often do we have to be told by secondary characters that a heroine really is heroic and admirable and inspirational…?

Walk through the aisles of any Barnes & Noble and you see the same cover concept over and over: a brilliantly dressed female hero, standing around… looking cool! It is the very antithesis of dynamism. Nothing is at stake. Nothing is happening. There is no danger. There is nothing to thrill or titillate. Decades ago, paperback covers would promise all manner of wonders and adventure. Today’s books offer little more than a mirror to an essentially effeminate audience. And judging a book by its cover really is a safe bet in this case. After all, how often do we have to be told by secondary characters that a heroine really is heroic and admirable and inspirational…?

Heroism in the age of the participation trophy is merely just another term for protagonist. And there is no consciousness of just what is lost when traditional archetypes are given arbitrary sex changes. The only reason this is possible is because contemporary tellings of old style adventure stories have quietly redefined, dumbed down, or cut out entirely anything related to men and manhood.

That sounds crazy, but it certainly explains the bizarre things that are done when iconic characters are translated into film these days. In The Lord of the Rings, Aragorn has travelled the world and served in the armies of two nations. He has spent decades fighting fell things in the North and discreetly protecting the Shire. He knows himself and he knows what must be done. His only doubt pertains the question of when and how. In contrast to this, the Aragon of film is all about “becoming”… and he even has to be scolded by his future father-in-law in order to get on the right track. A character which is the very picture of maturity is reduced to the sort of identity crisis that is beneath even the most immature hobbit.

From Unforgiven to Superman Returns and on to Elysium, we are presented with heroic looking figures that don’t even rate a steady girlfriend. I’m not exaggerating when I say this, either: Samwise Hamfast was twice the man of any of them.

And that’s why picking up an old classic is as shocking as it is. For many of us, this is going to be the first time we see men portrayed in fiction with anything remotely like normal, real-life motivations. Consider:

“Sigurd, Trygg’s son, am I! Jarl’s grandson! Master of Dragons!” His voice was low, yet in it was a clanging echo of smiting swords; and he spoke with eyes closed as though he stood before some altar. “Blood brotherhood is there now between us, Kenton of the Eirnn. Blood brothers–you and I. By the red runes upon your back written there when you thrust it between me and the whip. I shall be your shield as you have been mine. Our swords shall be as one sword. Your friend shall be my friend, and your enemy my enemy. And my life for yours when need be! This by Odin All-Father and by all the Aesir I swear–I, Sigurd, Trygg’s son! And if ever I break faith with you, then may I lie under the poison of Hela’s snakes until Yggdrasill, the Tree of Life, withers, and Ragnarak, the Night of the Gods, has come!”

I love this. In the first place, you have this Norseman dropped into the story straight out of legend and myth. The situation in this book is just so out there, too: a magic ship, unfamiliar Babylonian goods, weird magic. And Merritt just drops in one of the most iconic characters out of all history, myth, and legend just because he can. In a similar vein, the invocation of Ireland here is oddly comforting– an example of contrast that is lost when a fantasy presented as a self-contained Never Never Land with no connection to the real world. But there’s more: Loyalty. Brotherhood. Dreadful oaths. Invocations of gods and fathers and grand-fathers!

Is it fair to say that contemporary film is short on this sort of thing…? Well, maybe there are some exceptions. The trend I’m seeing lately in everything from The Fast and the Furious to The Flash television series is ensembles made up of characters that don’t have families and that don’t aspire to form families to refer to refer to their group of adventuring buddies as their “family.” Rather than the sort of edge that you see with old Sigurd here, you get some airy sort of sentimentality. Maybe I’m sort of throwback or something, but that sort of thing just doesn’t strike me as corresponding to reality. It certainly doesn’t resonate with anything that really drives me. It’s awkward. Fake. Cringeworthy.

Men are of course motivated by a strong desire to maintain honor and win respect. If your aesthetic requires you to treat them as being interchangeable with women, you’re necessarily going to lose that. And there is more to men that just that, of course. There is also the matter of the acquisition of female companionship. The strangeness you tend to see on that point are the countless men in the media that placidly accept their place in some shade of romantic exile. That is by far the most off-putting aspect of everything from Luke Skywalker to Ender Wiggin to Superman to Finn. And let me tell you: it wasn’t like that in the twenties.

No, when Merritt was writing those sorts of bloodless mannequins would have been the exception rather than the rule. And the resulting drama when they actually went after what they wanted was downright explosive:

“What will this liar, weakling, and slave gain if he kills the black priest for you?” he asked bluntly.

“Gain?” she repeated blankly.

“What will you pay me for it?” he said.

“Pay you? Pay you! Oh!” The scorn in her eyes scorched him. “You shall be paid. You shall have freedom–the pick of my jewels–all of them–”

“Freedom I shall have when I have slain Klaneth,” he answered. “And of what use to me are your jewels on this cursed ship?”

“You do not understand,” she said. “The black priest slain, I can set you on any land you wish in this world. In all of them jewels have value.”

She paused, then: “And have they no worth in that land from whence you come, and to which, unchained, it seems you can return whenever danger threatens?”

Her voice was honeyed poison. But Kenton only laughed.

“What more do you want?” she asked. “If they be not enough–what more?”

“You!” he said.

“Me!” she gasped incredulously. “I give myself to any man–for a price! I–give myself to you! You whipped dog!” She stormed. “Never!”

Up to this Kenton’s play with her had been calculated; but now he spoke with wrath as real and hot as hers.

“No!” cried Kenton. “No! You’ll not give yourself to me! For, by God, Sharane, I’ll take you!”

He thrust a clenched, chained hand out to her.

“Master of this ship I’ll be, and with no help from you–you who have called me a liar and slave and now would throw me butcher’s pay. No! When I master the ship it will be by my own hand. And that same hand shall master–you!”

“You threaten me!” Her face flamed wrath. “You!”

She thrust a hand into her breast, drew out a slender knife–hurled it at him. As though it had struck some adamantine wall, invisible, it clanged, fell to her feet, blade snapped from hilt.

She paled, shrank.

“Hate me!” jeered Kenton. “Hate me, Sharane; For what is hate but the flame that cleans the cup for wine of love!”

Finally.

A character that’s like me!

A guy with emotions like mine, motivations like mine, and with drive and tenacity and daring to spare. And while all of us have varying degrees of style when it comes to execution and delivery, there is no doubt: this really is the baseline for normal when it comes to men.

And that sort of thing is just gone.

It’s the absence of this sort of thing that explains the static nature of today’s fantasy and science fiction book covers. Because if guys like this are on stage, there will be a reaction. There will be something at stake. Anything could happen really, but one thing is sure: the stock standard fantasy heroine will not be able to get away with just standing around… looking cool.

That just isn’t an option when guys like this are around.

Yeah, the Kenton/Sigurd dynamic is great. The Persian and Gigi are pretty awesome as supporting characters as well.

Sharane is no shrinking violet. She’s fought the priests of Nergal for, literally, thousands of years. She and her handmaidens are effective archers. Noblewomen have been trained to the bow for millennia. What they are NOT is shock troops for close combat. Close reading of “Queen of the Black Coast” shows that Belit was an archeress, but no swordswoman at all.

Sharane, like Belit, is all in for her man once she decides he is the ONE. Which is how it should be.

I had forgotten all about Sigurd. It has been too long since I read this book, and I think I loaned it to someone. Bugger.

Deuce, I see what you mean about the elements in Queen of the Black Coast that Howard took from Merritt’s classic.

Damn but Merritt was good at this.

The sort of cover you lambast has become a blur. I spend too much time with writers, seeing their cover reveals, yawning. I love those o!d sci fi covers. They started out as paintings, a lot of them. Some horrible, some weird, but always an interesting dynamic going on.

To offer some defense of Card, Ender was shown as a sad failure for reasons including his lack of a family. Savior of the human race, and he winds up raising some studly xenador’s kids on Planet Brazil, and it is shown as a sad thing. When his soul is given freedom to choose, he chooses to abandon his hermitage with Novinha and be with Peter, in effect abandoning the feminine side of his personality (and allowing Jane to claim hers) for the adventures of Peter and Wang-Mu. Miro is another example of a hero who gets the girl, and he has to climb over a torture fence to do it too.

It’s notable that the core Ender saga ends with a double wedding.