Spend enough time reading science fiction, and readers will come across the idea of the Big Three of classic science fiction. Always a controversial selection, as the list of worthy grandmasters of the genre exceeds the places available in any Big Three, the current consensus is that Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, and Robert Heinlein represent the Big Three of science fiction. Except for those who prefer the acrostic list of Asimov, Ray Bradbury, and Clarke as the ABCs of science fiction. In either form, the Big Three are held up as the leading lights of the past era, referred to as the Golden Age or the Campbelline Age. But this view is from the safety of fifty years’ reflection. Did the readers of the Golden Age share this modern conceit?

Spend enough time reading science fiction, and readers will come across the idea of the Big Three of classic science fiction. Always a controversial selection, as the list of worthy grandmasters of the genre exceeds the places available in any Big Three, the current consensus is that Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, and Robert Heinlein represent the Big Three of science fiction. Except for those who prefer the acrostic list of Asimov, Ray Bradbury, and Clarke as the ABCs of science fiction. In either form, the Big Three are held up as the leading lights of the past era, referred to as the Golden Age or the Campbelline Age. But this view is from the safety of fifty years’ reflection. Did the readers of the Golden Age share this modern conceit?

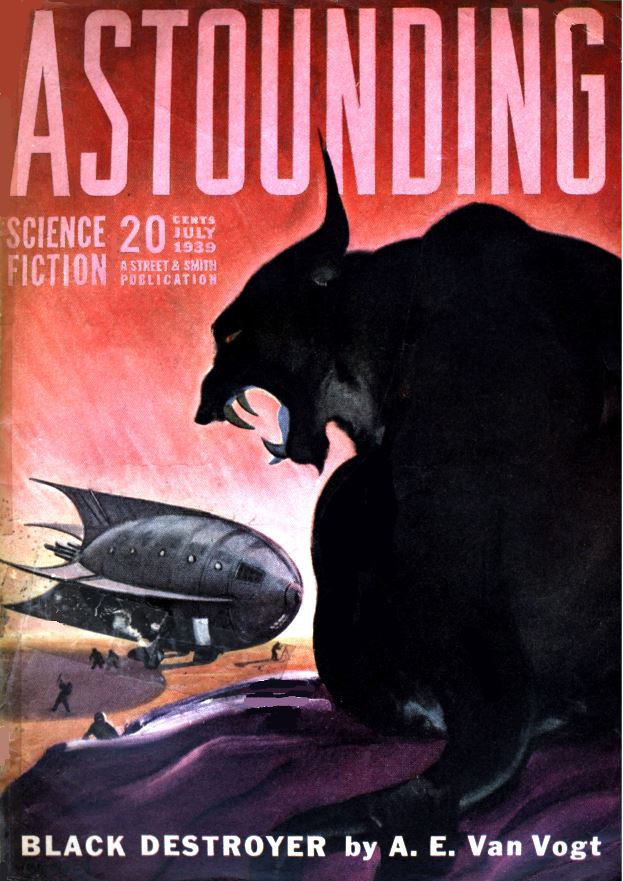

First, let’s narrow down what is meant by the Golden Age of Science Fiction. Depending on the critic or the fan, this could be as short as from 1939 to 1943 or as long as from 1939 to the early 1970s. And this vast range is further compounded by the fact that many of the same authors and editors who opened the age were still active at the close. John W. Campbell, who opened the Golden Age as the editor of Astounding Magazine with A. E. van Vogt’s “Black Destroyer”, continued to edit Astounding until his death in 1971. Asimov, Bradbury, Clarke, and Heinlein, who wrote highly-regarded short stories in the 1940s, released just-as-influential novels and collections in the 1960s and beyond, even into the 2010s in the case of Bradbury’s A Pleasure to Burn. However, lost in the glow of longevity are the turbulent 1950s, when science fiction was yet too small for writers to specialize in the genre, and many of the cherished writers of the 1940s left science fiction for Hollywood and other, more lucrative writing pursuits. Even Asimov seemingly left science fiction in the mid-1950s, only to return with 1966’s Fantastic Voyage, when the market could finally support dedicated science fiction writers. Therefore, for the sake of this article, the Golden Age instead will refer to the time when the first generation of Astounding writers–Henry Kuttner, van Vogt, Asimov, and Heinlein–were initially active, from 1939-1955.

Sources close to that time, such a 1959’s Fancyclopedia 2, offer different views of the term. The Big Three, as a consensus of the leading authors of the genre, starts to take a familiar shape as early as 1949. Fancylcopedia 3 describes the Big Three as:

Later, the Big Three was more likely to refer to towering figures among pros during the Golden Age. Two were indisputable: Robert A. Heinlein and A. E. van Vogt who almost defined the new SF of 1938-1948. (The third of the Big Three was usually whoever among Asimov, Bradbury and Clarke the speaker liked best.)

Like Asimov, van Vogt would take a hiatus from writing science fiction in the 1950s, with L. Ron Hubbard’s Dianetics claiming his imagination and fandom’s politics claiming his reputation. Although he returned in the mid 1960s, he never reclaimed his earlier place in the imagination of readers. But the earliest version of the Big Three referred not to authors but to the three highest regarded magazines of the time. This usage lasted from 1939 to shortly after 1959, and the listing of the best magazines shifted with prestige, circulation, and, most important to a readership eager to try its hand at writing, acceptance rate.

To the surprise of no one, Astounding was the permanent fixture of this Big Three. Campbell’s term as editor raised the magazine’s prestige to the point that it became the sole survivor of Street & Smith’s various pulp purges. However, from its founding, Astounding provided two important requirements not found in other science fiction pulps of the day–it paid well and, most significantly, it paid on time. Its companions included Amazing and Wonder Stories, then Famous Fantastic Mysteries and Unknown, with Unknown soon to be replaced by the “Standard Twins” of Thrilling Wonder Stories and Startling Stories, until, in 1949, Fantasy & Science Fiction and Galaxy joined Astounding as the bedrock magazines of the 1950s. Weird Tales did not make this list for a trio of reasons: a boycott of writers when Farnsworth Wright was let go as editor, the subsequent move away from science fiction, and an noncompetitive rate per word compared to Astounding and others.

It may be that in the future, the Big Three of Science Fiction may take on another shape. However, the proliferation of science fiction titles and the fragmentation of readership into finely-graded niches might lead one to believe that the current trio of Asimov, Clarke, and Heinlein might remain definitive for a good while.

I’m fine with Heinlein and van Vogt. Asimov? Gimme a break. Clarke could do “sense of wonder” fairly well, but I’d still rather read Bradbury in many ways. Also, Ray never talked trash on the pulps. Quite the opposite.

Somebody needs to edit Fancyclopedia:

“The third of the Big Three was usually whoever among Asimov, Bradbury and Clarke the speaker liked best.”

“Whomever.” One of the joys of reading the pulps is that the level of English is actually higher than what is considered “good English” now, even in “literary” circles.

There are some who would say the pulps were the golden age of SF and Campbell with his “big men with screwdrivers” was an also ran. I say this as a Heinlein fan.

-

I was more interested in the fact that the Big Three originally referred to magazines, not authors. I’m also increasingly convinced that we look back through a glass darkly at science fiction history because of the 1970s.