The Three Epochs of RPGs

Wednesday , 14, January 2015 Ken Games, Tabletop Games, Traveller, Uncategorized 3 CommentsThere are lots of ways to slice and dice the history of RPGs, and people like Sandy Antunes have written some incredible histories of the founding of the era. Me, I’m a game designer. I write rules. Writing rules for games is one of the weirdest kinds of writing to contemplate, because it’s a combination of programmer’s high and writing procedures manuals…for how to have a particular kind of fun. My perspective on the history of roleplaying games stems from a rules writer’s perspective, and isn’t quite congruent with the conventional view.

To me, the three epochs of RPGs are differentiated by what the games attempt to do, and how they’re trying to go about it. The first era had very little architectural design in the creation of the rules engine. Character customization was minimal, and the play itself was the reward; one of the great underappreciated rules of D&D was that your experience was based on the gold recovered, not the things you killed or the challenges met. In a very real sense, roleplaying games of this era treated characters as disposable artifacts: If you died, you’d be reintroduced with a new character found somewhere else in the dungeon. Much of the reward of play wasn’t “I came up with the perfect plan, and we executed it” – it was “I totally talked my way out of a situation where I shoulda died.” The play style rewarded was one of at-the-table improvisation, and an adventure was more of a sketch that everyone filled in. One of the reasons for the “sketch an adventure” method of creation was a combination of publishing schedules (TSR was trying to release around 20 32-page modules per year at its peak) combined with a bit of conservatism about not killing the goose with the golden egg.

To me, the three epochs of RPGs are differentiated by what the games attempt to do, and how they’re trying to go about it. The first era had very little architectural design in the creation of the rules engine. Character customization was minimal, and the play itself was the reward; one of the great underappreciated rules of D&D was that your experience was based on the gold recovered, not the things you killed or the challenges met. In a very real sense, roleplaying games of this era treated characters as disposable artifacts: If you died, you’d be reintroduced with a new character found somewhere else in the dungeon. Much of the reward of play wasn’t “I came up with the perfect plan, and we executed it” – it was “I totally talked my way out of a situation where I shoulda died.” The play style rewarded was one of at-the-table improvisation, and an adventure was more of a sketch that everyone filled in. One of the reasons for the “sketch an adventure” method of creation was a combination of publishing schedules (TSR was trying to release around 20 32-page modules per year at its peak) combined with a bit of conservatism about not killing the goose with the golden egg.

Traveller’s original character generation system (rolling for lifepaths to see what skills you got, and maybe dying in character creation) is a product of this era – and it provided a “solo play” mode for the game. Every Traveller player I know from this era can tell me war stories about rolling up dozens or hundreds of characters that never saw the table in actual play. Most also have a story about this character who got utterly fantastic skills…and who died because they pushed their luck one time too many through the careers choice.

The second epoch is differentiated by more detailed character creation rules, and in particular, character creation rules where players get to choose things about their characters. I trace this back to The Fantasy Trip, and later Man-to-Man by Steve Jackson. Both of these are clear predecessors of GURPS. Steve himself says that Champions was an influence, but I think there’s a decent argument for parallel development.

The second era of roleplaying games wasn’t a sharp transition. D&D and AD&D met the demand for “more character creation options” with more classes, a bolted on skill system, and then later, kits for D&D 2nd Edition. It didn’t become a true “second epoch design” until 3rd edition.

In this era, game rules were meant to definitively define the world. D&D picked this up and ran with it, and GURPS tried to define the world-by-physics model. Champions, which had spawned Justice, Inc, and a few other very similar games, codified to the Hero System in this span of time.

Once character customization became a standard practice, the RPG industry exploded. Prior to player-choice driven character customization, the secondary market for products was books of monsters and 32-page adventures that barely broke even. Both books sold to game masters, but not to players as much. Now that there were character choices to be made, character creation was, to quote Robin D. Laws, “Buying the Sears Catalog of Superpowers.” Now, new products – so long as they had additional options for character creation – would sell to roughly 60 to 80% of the customer base that bought the basic game.

This era of RPGs also made licensed RPGs a viable publishing niche. If you’re using the RPG to define the world according to a set of rules, you can use an RPG to define the setting of a movie to a fare thee well. Ghostbusters RPG by West End Games was the first really successful movie tie-in RPG, and it spawned the Star Wars Roleplaying Game using the D6 system.

The second era of RPGs is still with us – Pathfinder picked up D&D 3.5’s rules base, tuned it up, and is now, nearly seven years after publication, hitting the “too many options, creaking and falling over…” RPG phase. You can tell that an RPG system has hit sclerosis when players talk about “builds” rather than “characters.”

The third era of RPGs almost didn’t happen. Its first real product was a game called Everway by Johnathan Tweet – and it pre-dates D&D 3.5. The third era of RPGs is focused on mechanical rewards for inter-character relationships. Inter-character relationships weren’t new to RPGs – but the concept that the game would reward you for them was. There had been games with political intrigue before, Vampire: the Masquerade and the other White Wolf Noun: the Gerund games are roleplaying games about clique rivalries. What made Vampire brilliant is that its clique rivalries resonate with the American High School experience, even to keeping your rivalries secret from higher authorities.

What made Everway different was that it could give bonuses based on your character’s motivations. Everway was a flop on the market, published by pre-Hasbro WoTC when they were flush with cash and before they purchased D&D from the shambling corpse of TSR. It vanished from the market fairly quickly – and is usually cited as an example of WoTC’s excesses in the era when it had more money than sense.

In a time when rules systems were bloating with quarterly or bimonthy releases of character options to scratch the “I want a character who’s Not Like Anyone Else’s” itch, Everway and its follow-ons were like trying to explain the taste of the color nine, since it was all about using different things – subjective things – to get the same bonus. Since those bonuses were largely handed out by the GM, this undermined the idea that the GM is the fair and impartial interpreter of the world. GMs are meant to be facilitators to explore conflict, moments of high drama and heroism.

While Everway was the first third-epoch RPG, or even a transitional form, the first widely copied third-epoch RPG is Ron Edwards’ Sorcerer. In Sorcerer, your relationship with the other player characters drive the bulk of the game. Your relationship with your demon – the entity that gives you power – is one designed to make characters (and to some extent, players) paranoid about messing up, and all of the mechanical advantages accrue from working over these relationships. Indeed, most of the usual tensioners in a traditional RPG “Do I succeed on task X?” are handwaved away as “Yes, you succeed.” Baker’s Advice definitely holds true:

“Only roll the dice when something interesting can happen from failure. Otherwise, say yes.”

One side effect of having character motivations and relationships be the character differentiation tools is that rules systems didn’t have to be encyclopedic tomes of every possible option under the sun, and little RPGs that were designed around three session stories (My Life With Master by Paul Czege) or even single sessions (Fiasco by Jason Morningstar) could stretch RPGs into different shapes and forms.

A complaint about third-epoch RPGs is that they aren’t really RPGs; they don’t have a fair and impartial judge interpreting rules from a book that you can also make a case from. They have a GM and other players making subjective calls about squishy human relationships, and some who are fans of the second-epoch design ethos claim they’re nothing more but slightly organized Mother-May-I sessions.

Anyone who’s played old school RPGs knows that that’s where the root of the hobby began: “I want to do X” “Yeah, sounds reasonable.” or “Yeah, that sounds risky. Still want to try it?”

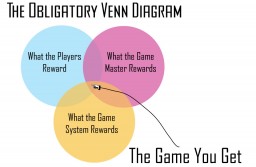

And since I’ve run longer than expected here, here’s the Obligatory Venn Diagram, which I mentioned last week and will go into more detail next week, when I put RPGs into a Skinner Box and see what comes out.

And since I’ve run longer than expected here, here’s the Obligatory Venn Diagram, which I mentioned last week and will go into more detail next week, when I put RPGs into a Skinner Box and see what comes out.

Yeah. I wouldn’t have guessed your timeline. I told ya I was just tossing darts!

Part of that is because, as much fun as I have had playing Dread or Dogs in the Vineyard occasionally as social/emotional game, they simply can’t compare to the crunch and evocation of a big, complicated and combat-oriented old rpg.

Then again, I loved Rolemaster’s massive catalog of crit charts. It was like the Sears & Roebuck of creative death scenarios.

-

Jeffro says:

“Yeah. I wouldn’t have guessed your timeline. I told ya I was just tossing darts!”

I’m not too humble to point this out, but… I totally called this!!!

-

Don says:

Ah Rolemaster the game that screamed for some kind of computer interface. So much so that my wife tried to build one on our Commodore 64.

It would be okay today with an ipad or something for each player.