The Word Made Flesh: On the Nature of Book-To-Film Adaptations (Part 1 – Literary Infidels)

Friday , 6, February 2015 Uncategorized 6 Comments

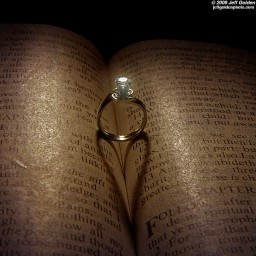

Do you take this book to be your lawfully wedded source material, to film and to direct, to love, honor, and obey, in production and in postproduction, keeping yourself solely unto its narrative for as long as you both shall live?

Picture courtesy of Jeff Golden, via Flickr

In the previous post, we looked at a few different book-to-film adaptations and answered the age-old question: which was better, the film or the book?

One of the common criteria for evaluating the success or failure of a film adaptation is its fidelity to the source material.

The truth is that fidelity, whether in the final product or even as an initial goal, is the exception to the rule.

Consider the vast attitudinal gulf that lies between J.R.R. Tolkien and Alfred Hitchcock on the subject:

The canons of narrative art in any medium cannot be wholly different; and the failure of poor films is often precisely in exaggeration and the intrusion of unwanted matter owing to not perceiving where the core of the original lies.

–J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter 210, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien

“There’s been a lot of talk about the way Hollywood directors distort literary masterpieces. I’ll have no part of that! What I do is to read a story only once, and if I like the basic idea, I just forget all about the book and start to create cinema.”

–Alfred Hitchcock, from an interview with François Truffaut, Hitchcock, p. 49

Poor Tolkien – he thought Hollywood just misperceived his intentions. What Hitchcock so frankly reveals is that filmmakers do not necessarily fail to apprehend ‘where the core of the original lies’; they aren’t even trying to apprehend it in the first place! By and large, they do not aim to be faithful. They are literary infidels – and they aren’t the only one.

Shakespeare famously borrowed plots — Hamlet was based on 12th century author Saxo Grammaticus’ Gesta Danorum (“Deeds of the Danes”). In Saxo’s version, Hamlet lives, and goes off to other adventures. Shakespeare, of course, opted for a slightly more downbeat ending.

‘Hey man’, an arrogant film director might say, ‘If Shakespeare borrowed plots and even changed them around too, what’s so wrong with that? Why can’t I add a little elf-dwarf romance to The Hobbit?’

First, because he is Shakespeare and you, Mr. Filmmaker, are not. Have a little humility. Yes, you can put your stamp on the material, just don’t stamp on it with your Orwellian boot; it’s not a face to be kicked in.

Second, because while in the process of adaptation you may end up borrowing plots, characters, and on rare occasions even the mysterious original ‘core’ of the material, what you are really wanting to borrow is the built-in fanbase of the book. Adaptation brings with it brand name recognition, literary cachet, and a marketing aura that brings box office gold. Any pledges of fidelity on your part are likely made to ensure that fans go see the movie. If all you want to do is ripoff some ideas and make it into your own thing, go do that. Make your elf-dwarf weepy romance fantasy, just don’t call it The Hobbit. Do as all other artists do and create by synthesis.

Now, Mr. Filmmaker, because of the unique challenges that every film production will face, I know you consider the screenplay more of a blueprint to follow than a bible to religiously adhere.

And this is true. A movie is written three times: on the page, in the camera, and in the editing bay. Sometimes a simple reaction shot from a talented actor can eliminate the need for an entire page of dialogue, or a moment of improvisation becomes the best line of the movie, or a location change will necessitate a rewrite. If they had followed the scripted version of the Ascent of Man section of 2001: A Space Odyssey (which was almost a word-for-word translation of the book) we never would have gotten the most famous jump cut of all time.

But sticking reasonably close to the source material and dramatizing its feelings and moods cinematically is not the same as inserting, in Tolkien’s words, “unwanted matter”.

Next week, we’ll take a look at some of the challenges inherent in translating a book to the screen.

“or a moment of improvisation becomes the best line of the movie”

I know.

Peter Jackson is on record as saying that while filming the LOTR movies, he and the writers kept finding the book’s ideas were better than theirs and discarding their ideas to film the book. I don’t know how true that is, but by the 3rd movie, he seemed to have “gotten Past” that feeling. And totally ignored it in the Hobbit.

-

Oh too true. I know that Return of the King would have been improved by Legolas sliding down the oliphant like Fred on the dinosaur when the whistle blows. But Tolkien had a story to tell and to narrate the slide and Legolas cutting the howdah off would have taken too long. God I hate Jackson sometimes.

And then you take a film like “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” and you wonder if the title was a mockery of the original story, since it bears no similarities to it at all. If I were to forget that it was a take-off of a Thurber short, I might say the film wasn’t stellar, but was saved by its lack of nihilism. And that’s ironic, I’d have to say.

Note that “2001: A Space Odyssey” the novel was written concurrently with the script. It was a collaboration with the filmmaker, so the film was *not* based on the book.

Similarly, “The Abyss” novel was written by Orson Scott Card based on James Cameron’s story, and I believe there was give and take in in story idea. There the novel is better because OSC is a much better storyteller than Cameron is.