THROWBACK SF THURSDAY: Changa’s Safari by Milton Davis

Thursday , 11, May 2017 Book Review 15 Comments Teen boys get a bad rap. David Hartwell sneered that “the Golden Age of Science Fiction is 12.” John Rogers gibed that “There are two novels that can change a bookish fourteen-year old’s life: The Lord of the Rings and Atlas Shrugged. One is a childish fantasy that often engenders a lifelong obsession with its unbelievable heroes, leading to an emotionally stunted, socially crippled adulthood, unable to deal with the real world. The other, of course, involves orcs.” And this while 22% of 13-year-olds say they “never” or “hardly ever” read for pleasure, versus 8% a few decades ago. And while 30% of girls read daily, only 18% of boys do.

Teen boys get a bad rap. David Hartwell sneered that “the Golden Age of Science Fiction is 12.” John Rogers gibed that “There are two novels that can change a bookish fourteen-year old’s life: The Lord of the Rings and Atlas Shrugged. One is a childish fantasy that often engenders a lifelong obsession with its unbelievable heroes, leading to an emotionally stunted, socially crippled adulthood, unable to deal with the real world. The other, of course, involves orcs.” And this while 22% of 13-year-olds say they “never” or “hardly ever” read for pleasure, versus 8% a few decades ago. And while 30% of girls read daily, only 18% of boys do.

I don’t get why we denigrate books as written for 12-year-old boys. If a book can get a boy excited about reading, that’s a magical book!

The problem is even worse for African-Americans. 23% of white Americans say they haven’t read a book in the past year. That’s a shame. 29% of African-Americans said the same. That’s a travesty. And where do you see all of the conversation around diverse voices focused? Octavia Butler, Sam Delaney, and N.J. Jemisin aren’t going to get black boys reading. But Changa’s Safari? This is a book you can hand a kid and light a fire for reading that will never burn out. And you will enjoy it too.

I saw Davis speak on a panel at JordanCon and walked away so impressed I swung by his author’s table the next day. I asked about a certain pulpy sound to Changa for the obvious reasons, and Davis described him to me as “Conan with a job.” Sold.

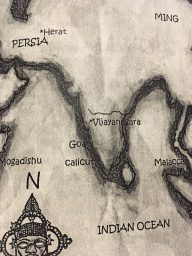

The job being merchant on the 15th century, pre-Portuguese Swahili coast of Africa. Captaining your dhows personally can make for some adventures, and Changa goes armed with sword, throwing knives, and wrist knife. He is accompanied by a sorceress, Panya, and a silent Tuareg who fights with takouba and scimitar. The adventures in volume 1 (Davis has a 2nd and 3rd volume out, with a fourth to come) start on the east African coast but range all the way to Mongolia. There was a rich trading economy at the time from stretched from the Swahili coast to the Middle Kingdom, all facilitated by Arabic merchants.

The job being merchant on the 15th century, pre-Portuguese Swahili coast of Africa. Captaining your dhows personally can make for some adventures, and Changa goes armed with sword, throwing knives, and wrist knife. He is accompanied by a sorceress, Panya, and a silent Tuareg who fights with takouba and scimitar. The adventures in volume 1 (Davis has a 2nd and 3rd volume out, with a fourth to come) start on the east African coast but range all the way to Mongolia. There was a rich trading economy at the time from stretched from the Swahili coast to the Middle Kingdom, all facilitated by Arabic merchants.

Changa’s Safari is novel-length but is really three novellas. The first, The Jade Obelisk, is a rather standard sword and sorcery yarn involving an evil sorceress, a demigod for an ally, and hyena-men mooks in Zimbabwe. A Certain Spice sees Changa embarking for Asia after an emissary from the Chinese emperor lands in Sofala. The third novella, The Emperor’s Ransom, continues the story from the second, with Changa getting roped into recovering the Chinese emperor from Mongol captivity, with Davis filling a gap in the real history. The structure keeps things punchy, and the stories get better as they go along. There are also advantages to writing the stories together versus the patchwork publication by pulp magazine. Pretty much my only complaint about the Silver John stories was the limited continuity.

Davis edited the Griots sword and soul anthology, reviewed here by Morgan, with Charles Saunders. Saunders has his own sword and soul hero, Imaro. Changa is a welcome addition to the niche sub-genre. Changa’s Safari stands up well against Robert E. Howard’s better imitators and is the better for the African influence (the “soul” in the “sword and soul”). Africa is vastly underappreciated in fantasy. The locales and source mythos keep what might otherwise seem a by-the-numbers sword and sorcery tale fresh. The stories are peppered with just enough Swahili to give them a flair of authenticity without leaving the reader confused. Davis adds distinct weapons like wrist knives (basically, big bracelets with sharpened edges that were used like a parrying dagger). Men fight on foot because the tsetse fly makes keeping herds of horses infeasible. Leaving Africa, Changa encounters pirates and komodo dragons and eunuchs and Mongols, not to mention sorcerers and demons and fire-mages. Mongols, in particular, deserve more faithful representation in fantasy.

Davis edited the Griots sword and soul anthology, reviewed here by Morgan, with Charles Saunders. Saunders has his own sword and soul hero, Imaro. Changa is a welcome addition to the niche sub-genre. Changa’s Safari stands up well against Robert E. Howard’s better imitators and is the better for the African influence (the “soul” in the “sword and soul”). Africa is vastly underappreciated in fantasy. The locales and source mythos keep what might otherwise seem a by-the-numbers sword and sorcery tale fresh. The stories are peppered with just enough Swahili to give them a flair of authenticity without leaving the reader confused. Davis adds distinct weapons like wrist knives (basically, big bracelets with sharpened edges that were used like a parrying dagger). Men fight on foot because the tsetse fly makes keeping herds of horses infeasible. Leaving Africa, Changa encounters pirates and komodo dragons and eunuchs and Mongols, not to mention sorcerers and demons and fire-mages. Mongols, in particular, deserve more faithful representation in fantasy.

It was interesting to read Changa’s Safari after reading Rick Stump’s analysis of the first Conan movie. Like Kull, and movie-Conan, Changa is a former slave and pit fighter. Like movie-Conan, Changa is motivated by avenging his father (but saving his mother and sister). Like movie-Conan, Changa spends a lot of time doing a lot of other things. But he will need money and power if he is to defeat the sorcerer who ruined his life. Davis keeps the backstory and motivation very light and subtle though. There is craft in that. Hollywood would dump an hour and a half of backstory on us. But these are universal themes. Davis knows we don’t need much to grasp what they mean to Changa. And like Howard’s Conan, Changa is “not just fierce and strong, [but] intelligent, insightful, and charismatic.”

The story lives and dies by the reader’s connection with Changa, and Changa is real in every way. The way nothing stirs his heart like a commercial proposition (he could be an honorary Scot). A corresponding gruff affectation that melts when it comes time to save someone. His relationship with Panya. His quieter relationship of mutual respect with the Tuareg. His discomfort with politics, even as his rising fortunes force him into a political role. The ambition that causes him to continually push farther and risk more. I feel like I know Changa. He’s that friend you stand in awe of and watch vicariously.

I have print copies of the first two volumes. There are some pretty annoying copyediting issues, but the covers are quite a bit better than the average self-published book, and they even contain black-and-white interior illustrations.

Volumes One, Two, and Three are all available in paperback and kindle at Amazon. I understand that a fourth and final volume is on the way.

H.P. is an academic, attorney, and “author” (well, blogger) who will read and write about anything interesting he finds in the used bookstore wherever he happens to be for the moment. He can be found on Twitter @tuesdayreviews and at Every Day Should Be Tuesday.

Sounds pretty good! Looks like I have new reading material to check out.

-

I think you’ll dig his work, Rawle. Milton’s entertaining to follow on FB. Where he finds the time with all his projects, I don’t know. He believes in getting things done. He’s grown from a first-time author to a one-man media powerhouse in 8yrs.

I got acquainted with Mr. Davis back in 2009 courtesy of Charles Saunders. I posted several times on the old Cimmerian blog about Milton’s projects:

http://leogrin.com/CimmerianBlog/saunders-changas-safari-and-meji/

I was preparing to review CHANGA’S SAFARI when we decided to shut down the TC blog. It’s a fun book. It’s obvious that it’s a first novel, but still fun.

I will say that Davis has worked hard at his craft and now he can hang with just about any of the S&S authors working today. His non-Changa tale in the new Skelos #2 is a standout in an issue with several other fine tales of S&S. Keep an eye on Milton.

-

Ooh, Skelos no. 2 has been sitting on my shelf. Now I have another reason to pick it up.

I saw definite improvement over the course of just these three stories. I’m looking forward to vol. 2. I think this book is better than Jordan’s Conan stories or The King of the Bastards, if not The Tritonian Ring.

https://everydayshouldbetuesday.wordpress.com/2016/02/24/review-king-of-the-bastards-brian-keene-stephen-l-shrewsbury/

I’d also recommend the works of Derrick Ferguson if you’re looking to show young, black men how reading doesn’t have to be dull and painful. His modern day adventures feature an action hero in the Carl Weathers vein. He even has a ‘prequel’ featuring young Dillon:

https://www.amazon.com/Young-Dillon-Shamballah-Derrick-Ferguson/dp/1497539900

I found them lacking in depth – they are unapologetically light, popcorn fare – but in many cases that’s just what you need to set the hook. And frankly, even if they don’t graduate to heavier or more srs fare…so what? Getting somebody from no reading to any reading is still a win.

-

“Action hero in the Carl Weathers vein” sounds right up my alley, but I wish more self-published authors would spring for Changa’s Safari quality cover art, not Young Dillon quality cover art.

Props on the Changa recommend! As evidenced by Davis’ Changa (very good character), Saunders founded a potentially productive sub genre with Soul and Sorcery. Here’s hoping for a broader audience for Davis and Saunders!

The Changa stories are terrific and deserving of better attention. They are some serious, old-school S&S using settings and cultures left egregiously untapped by the genre. I’ve reviewed most of them at my site or Black Gate.

Same for Milton’s excellent Griots anthologies. There are some topnotch authors I’ve rarely seen outside of these books, and it’s a damn shame.

Like Deuce wrote, Milton’s some kind of powerhouse – writing, publishing, editing, promoting – and he’s got a day job.

I don’t get how you read David Hartwell’s statement as a ‘sneer’. Looking at his book “Age of Wonders”, especially the first chapter, I get the impression that, if anything, he admires the twelve-year-olds who read science fiction, and thinks them rather normal than otherwise.

-

Hartwell himself leaves the sentiment largely unexplored, so we can argue over what he was implying. I tend to side with the VanderMeers:

“The reason readers argue about whether the Golden Age occurred in the 1930s, 1950s, or 1970s, according to Hartwell, is because the true age of science fiction is the age at which the reader has no ability to tell good fiction from bad fiction, the excellent from the terrible, but instead absorbs and appreciates just the wonderful visions and exciting plots of the stories.

“This is a strange assertion, one that seems to want to make excuses. It’s often repeated without much analysis of how such a brilliant anthology editor . . . would want to (inadvertently?) apologize for science fiction . . . .”

The Big Book of Science Fiction, xiv

I think Hartwell is not just being unfair, but wrong on the substance. My favorite book when I was 12 was . . . the Lord of the Rings. Yeah, that one holds up. And it is exactly the sort of book that people intent on presenting themselves as sophisticated love to denigrate. It is also one of the monumental works of literature from the past century, as Tom Shippey pretty dispositively shows in Author of the Century. A 12 year old can recognize that instinctively, even if they don’t fully appreciate the full richness of themes and the history behind it. It’s adults who trick themselves into thinking otherwise.