He likes it that way. The whole “lonely hero” thing.

He likes it that way. The whole “lonely hero” thing.

The other day, with my wife out of town and having set aside my work at the early hour of 8pm, I was looking for something to watch. I would up watching Hellboy for the first time in at least a few years. I was immediately struck by how pulpy it is. A quick Google search confirms I am not the first person to have the thought, but there is more to it than immediately meets the eye.

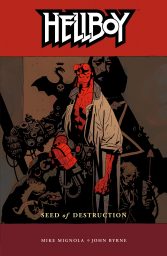

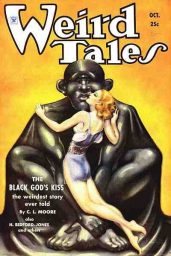

Hellboy is totally pulp. And not just because it has a tentacled space monster. Mike Mignola, the writer-artist of the original comic, points to Lovecraft, but he also points to Robert E. Howard. And not just to Conan but to Solomon Kane. And not just to Howard but to Manly Wade Wellman. Now you have my attention.

Mignola—and Guillermo del Toro, through his film adaptation—haven’t just created the superficial sort of homage to the pulps that you more typically see. It goes beyond throwing in some tentacles and vivid imagery (let us all pause and give thanks for Guillermo del Toro). Hellboy is pulp in every sense of the word.

How so? Read on and find out. (With the caveat that I’ve never read the comics and haven’t seen the second movie in a long time, so I will be focusing entirely on the first movie.)

The defining moment is right at the beginning. Professor Bloom offers Sgt. Whitman a rosary. The sergeant offers Professor Bloom a revolver in return. Hellboy is the sort of story where both come in handy.

It is set within a Christian worldview. Not in that it in any way proselytizes, but in that the mythology borrows heavily from Christianity, without subversion. Professor Bloom’s Catholicism is established early. When asked if he believes in Hell, he doesn’t mock the questioner, but rather states outright that “there is a dark place.” Hellboy’s appearance is that of a traditional devil. And, uh, his name is Hellboy. Abe had a reliquary for a minute there; its loss is a signal of the danger he is in. When Agent Myers tosses Hellboy Professor Bloom’s rosary at his point of greatest temptation, the cross burns his palm.

It is set within a Christian worldview. Not in that it in any way proselytizes, but in that the mythology borrows heavily from Christianity, without subversion. Professor Bloom’s Catholicism is established early. When asked if he believes in Hell, he doesn’t mock the questioner, but rather states outright that “there is a dark place.” Hellboy’s appearance is that of a traditional devil. And, uh, his name is Hellboy. Abe had a reliquary for a minute there; its loss is a signal of the danger he is in. When Agent Myers tosses Hellboy Professor Bloom’s rosary at his point of greatest temptation, the cross burns his palm.

It is a tale of good v. evil. Professor Bloom, Hellboy, Abe, Liz, Myers—all have a moral core and clearly are on the side of the “good.” The only possible exception being Jeffrey Tambor’s bastard bureaucrat of a boss, and even he gets a bit of heroic redemption. The bad guys, on the other hand, are unremittingly evil. No backstory is told to explain away their vile behavior. Indeed, backstory only serves to underscore just how evil they are. When Professor Bloom contemplates Kroenen, he doesn’t ask what must have been done to him to make him so evil; he asks “what horrible will could keep a creature such as this alive?” Agent Myers’ role in the plot is as moral guide, taking over for Professor Bloom. “In medieval stories, there is often a young knight who is inexperienced, but pure of heart. . . . You will help him, in essence, to become a man.”

Hellboy is a man of action. He doesn’t wait around for Type 2 permits before engaging in a little amateur demolition when his enemies are on the other side. (Trigger warning: Nazis get punched. And shot. And bayonetted.). Violence and action are accepted methods of dispute resolution. “What makes a man a man? A friend of mine once wondered. Is it his origins? The way he comes to life? I don’t think so. It’s the choices he makes. Not how he starts things. But how he decides to end them.” Hellboy and his team exist for those times in which things need to be ended with extreme prejudice.

Hellboy fully commits to its pulp ethos in the final act. Rasputin tempts Hellboy not with dominion over earthly kingdoms but with the life of his soulmate, Liz. This is sticking a barbed tentacle right in one of my sore spots. How often in Hollywood have we seen our so-called hero refuse the call to fight for Man, only to reverse course after his family is threatened or harmed? It presupposes that we are so selfish and small that we would never fight for more than our own little tribe. It’s a narrow, mean concept of heroism that isn’t at all heroic, and disparages the family by association. In the more usual sort of story, that is. But Hellboy looks not just to the love of his life, but to what he was taught by his father figure, to what his brother figure even then is reminding him of. Knowing it will cost Liz her life, he rejects evil and strikes against it. Liz is only saved after he fully commits to that sacrifice. And after he threatens to pull a Jirel of Joiry.

Hellboy fully commits to its pulp ethos in the final act. Rasputin tempts Hellboy not with dominion over earthly kingdoms but with the life of his soulmate, Liz. This is sticking a barbed tentacle right in one of my sore spots. How often in Hollywood have we seen our so-called hero refuse the call to fight for Man, only to reverse course after his family is threatened or harmed? It presupposes that we are so selfish and small that we would never fight for more than our own little tribe. It’s a narrow, mean concept of heroism that isn’t at all heroic, and disparages the family by association. In the more usual sort of story, that is. But Hellboy looks not just to the love of his life, but to what he was taught by his father figure, to what his brother figure even then is reminding him of. Knowing it will cost Liz her life, he rejects evil and strikes against it. Liz is only saved after he fully commits to that sacrifice. And after he threatens to pull a Jirel of Joiry.

It’s not a perfect movie. It’s not a great movie. Hellboy was made during that dark time when filmmakers could do a lot of things with CGI that they really shouldn’t have (the Star Wars prequels are the worst violators, of course, but this holds back the Lord of the Rings movies, and the Gone and Sixty Seconds and Dukes of Hazzard remakes each have a really egregious CGI car jump). Ron Perlman carries the movie, and John Hurt and Doug Jones are excellent, but Selma Blair and Rupert Evans are dull as dishwater. The plot is a bit of a mess, and the villains a little too boring, and not nearly weird enough (Kroenen not included). But it is not hurt by embracing the pulp ethos. Quite to the contrary, that is why it is still worth picking up today.

As you entered the lobby there was an inscription: “In the absence of light, darkness prevails.” (In Absentia Luci, Tenebrae Vincunt). There are things that go bump in the night, Agent Myers. Make no mistake about that. And we are the ones who bump back.

Next week: is Hellboy hard science fiction?

H.P. is an academic, attorney, and “author” (well, blogger) who will read and write about anything interesting he finds in the used bookstore wherever he happens to be for the moment. He can be found on Twitter @tuesdayreviews and at Every Day Should Be Tuesday.

Right on! Very nearly the same review I would’ve written.

Mignola’s entire literary universe pretty well exemplifies the “pulp fiction” concept/ethos/aesthetic. Mignola throws in what will make for a great, fast-moving story, unbound by any particular “genre” constraints. ENTERTAINMENT is the goal.

-

I definitely want to pick up the comics in the near future.

It is. Such a good comic AND movie, which is rare.

You should really read the comics. They are a unique blend of pulp and mythology. The art is so moody and perfectly adapted to the whole story style. Great, fun stuff!

The movie is pretty good. I think it pales compared to the comics, but it’s probably about as good as you can hope for from a big budget film.

I don’t think Del Toro really groks Hellboy as much as he thinks because he loads him up with quirks like cat hoarding and being a slob and the whole “he’s just an overgrown teenager” angle, which sort of misses that what makes Hellboy appealing (at least to me) is how disarmingly non-freakish he is once you get past his appearance. He really is just a regular dude who punches monsters in the face for a living, same as a plumber fixes toilets. Del Toro’s Hellboy is a bit too switched on and obnoxious all the time.

I was re-reading the original miniseries recently and I remember one of neatest scenes is in the middle of all the Lovecraftian craziness, Mignola throws in a random scene of aliens monitoring the situation on an extra-dimensional space station. They never show up again and, at least as far as I’ve read, they’ve never been explained. It’s just that kind of universe.

The comics are the best, and the first movie’s pretty terrific too. Mignola’s in-universe character, Lobster Johnson, is pure pulp hero greatness.

I love both the Hellboy comics and the movies. They do differ on some key points. The Hellboy and Liz Sherman in love plot line in the first movie is one example.

I dearly love the scene towards the end of the movie where Hellboy is holding Liz Sherman’s dead body. He seems to whisper in her ear and suddenly she seems to snap back to life. She asks him:

“In the dark I heard your voice, what did you say?”

Hellboy: “I said, “Hey, you on the other side, let her go. Because for her, I will cross over…and then you will be sorry!”

Now that is both badass and romantic; a tricky combo to pull off.