THROWBACK SF THURSDAY: The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian by Robert E. Howard

Thursday , 6, July 2017 Appendix N 12 CommentsHither came Conan, the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet.

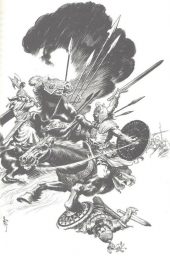

The first volume of Del Rey’s three-volume collection of Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories is my introduction to Howard and almost my introduction to Conan. The Del Rey editions collect the stories in the order that Howard wrote them rather than by publication date or plot chronology.[1] The first book includes a foreword by Mark Schultz and an introduction by Patrice Louinet. Both are excellent, neither denigrating the source material. Louinet is the editor, and Schultz contributed extensive illustrations (I understand these are missing from the Kindle version). He is no Frazetta—no one is—but I like Schutlz’s artwork a lot, and I find it supplanting Frazetta and the Ah-nold movies in how I picture Conan and his world. They do tend to be a little spoilery. The first volume also includes drafts, synopses, and, most notably, Robert E. Howard’s fictional history of the Hyborian Age.

The first volume of Del Rey’s three-volume collection of Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories is my introduction to Howard and almost my introduction to Conan. The Del Rey editions collect the stories in the order that Howard wrote them rather than by publication date or plot chronology.[1] The first book includes a foreword by Mark Schultz and an introduction by Patrice Louinet. Both are excellent, neither denigrating the source material. Louinet is the editor, and Schultz contributed extensive illustrations (I understand these are missing from the Kindle version). He is no Frazetta—no one is—but I like Schutlz’s artwork a lot, and I find it supplanting Frazetta and the Ah-nold movies in how I picture Conan and his world. They do tend to be a little spoilery. The first volume also includes drafts, synopses, and, most notably, Robert E. Howard’s fictional history of the Hyborian Age.

The stories in this volume are shorter than the stories in the other two volumes. I’m not going to review each, or even the volumes as a whole, really. You’ve probably read the Howard stories and Jeffro’s Retrospective post (if you haven’t, stop reading this and do both). I will save the reviews for the pastiches, but I do have plenty to say about Howard’s stories. I will have a whole lot to say about Conan before it is all said and done.

The dichotomy Howard draws between barbarianism and civilization is oft remarked on by commentators, not the least because Howard himself quite plainly lays it out. But there is more to it than a cursory, simplistic interpretation might imply. My impression of Conan was sealed by two of the first four stories—The God in the Bowl and The Tower of the Elephant.

In each, Conan is a young thief. He doesn’t wear his role as a barbarian in civilized lands as comfortably as he does as an older man. This is a Conan who reacts to his discomfort with civilized society with anger and violence. In The God in the Bowl, Conan is loath to admit he came to the Temple to steal, but he reacts viciously when the watch thinks to seize him.

In each, Conan is a young thief. He doesn’t wear his role as a barbarian in civilized lands as comfortably as he does as an older man. This is a Conan who reacts to his discomfort with civilized society with anger and violence. In The God in the Bowl, Conan is loath to admit he came to the Temple to steal, but he reacts viciously when the watch thinks to seize him.

“Back, if you value your dog lives!” he snarled, his blue eyes blazing. “Because you dare to torture shop-keepers and strip and beat harlots to make them talk, don’t think you can lay your fat paws on a Hillman! I’ll take some of you to hell with me! Fumble with your bow, watchman – I’ll burst your guts with my heel before this night’s work is over!”

In The Tower of the Elephant, Conan naively asks about the tower, brazenly declares he could burglarize it, and then kills the man for laughing at him.

It is not the loincloth that makes the barbarian.

Howard wove tales more distinctively American than George R.R. Martin, who sometimes gets called the American Tolkien. Howard’s are the true rivals to Tolkien’s English tales. The Hyborian Genesis essay from the Appendices suggests Howard conceived of Conan while wandering the Texas-Mexico border, with his “main occupation being the wholesale consumption of tortillas, enchiladas and Spanish wine” (Howard’s words, but after my own heart). His fictional history of his created epoch, The Hyborian Age, shows a rich appreciation for the often-bloody flow of people over time. Too little fantasy does. Howard, though, had the benefit of being from Texas. The flags of six different sovereigns famously flew over Texas over the course of just a few hundred years. The southern border has always been porous. At the time of the Texas Revolution, the Comanche probably still outnumbered both Anglo and Tejano Texans, and controlled more of Texas, including Howard’s future home.

Howard’s true forebears may not be modern epic fantasy, but rather post-apocalyptic fiction. The Mongol-inspired orcs from The Lord of the Rings literally dehumanize barbarians. Barbarians, of whatever sort, are usually explicitly evil or noble savages in traditional fantasy. Howard knew better, and while Conan never sets foot back in Cimmeria, he travels through the lands of many barbarians, from kozaks to Afghulis. Where so much fantasy uses whatever sort of barbarians as a foil, Howard saw civilization as inherently trending toward the decadence that would be its downfall. Fear of the same is much of what drives the popularity of zombie fiction today and leads people to make silly analogies between dystopian fiction and politics.

Howard’s true forebears may not be modern epic fantasy, but rather post-apocalyptic fiction. The Mongol-inspired orcs from The Lord of the Rings literally dehumanize barbarians. Barbarians, of whatever sort, are usually explicitly evil or noble savages in traditional fantasy. Howard knew better, and while Conan never sets foot back in Cimmeria, he travels through the lands of many barbarians, from kozaks to Afghulis. Where so much fantasy uses whatever sort of barbarians as a foil, Howard saw civilization as inherently trending toward the decadence that would be its downfall. Fear of the same is much of what drives the popularity of zombie fiction today and leads people to make silly analogies between dystopian fiction and politics.

The Hyborian Age may be doomed, but Conan is not. Conan soldiers and thieves and drinks and kills through the Hyborian Age with joy and abandon. His only sorrow is behind him, in Cimmeria. Tis no surprise, then, that in Howard’s fictional history the remnants of the remnants of the Cimmerians would become the Gaels, “the men that God made mad, for all their wars are merry, and all their songs are sad” (Chesterton).

[1] Howard’s own reasoning is as good as any. “In writing these yarns I’ve always felt less as creating them than as if I were simply chronicling his adventures as he told them to me. That’s why they skip about so much, without following a regular order. The average adventurer, telling tales of a wild life at random, seldom follows any ordered plan, but narrates episodes widely separated by space and years, as they occur to him.”

I love this set of the Conan stories, I just finished re-reading my hardcover of The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian last month. I love these stories they are more a part of me than Tolkien ever has been. I feel like I’ve known of Conan all my life even before I ever read a single word that Howard wrote. I was 17 when Conan the Barbarian, the John Milius movie came out but I had already been a Conan reader before that. My first exposure to Conan was with the De Camp & Carter books. Before I read Donaldson, Kurtz, Eddings and eventually Tolkien (Tolkien came much later) there was Conan for me. Most days if you saw me at school I either had a Don Pendleton Executioner novel with my pile of school books or a Conan book.

Great post!

I’m not familiar with Mark Schultz’s art, but if these two pictures are representative of his work, I can see what you mean. If all three books have art like this, they would make a great gift (or the first book, a great introduction) for more than one person I know.

Thanks for the post.

-

The other two volumes have art by different artists, but they are all quite good.

-

Schultz got his start writing and drawing a post-apocalyptic adventure comic called Xenozoic Tales, which in the early 90s got a modest multimedia push as Cadillacs and Dinosaurs. (I guess he’s still technically creating the comic but the latest issue is something like 20 years late now….)

He’s not a bad writer and his art is just gorgeous, kind of in that Frazetta tradition but with his own spin on it.

I don’t remember where i read it and perhaps it is even in the forward of the book, but my understanding is the Conan reprints of the 60s and 70s were edited and this book (as well as the other volumes) in contrast reprinted the originals from Weird and elsewhere unedited.

-

I didn’t know that!

Hmm, I need take a look at these.

Thanks, HO!

-

From the editor’s introduction: “[U]ntil the present publication, Howard’s Conan stories had never been published as Howard wrote them, in the order in which he wrote them, in a uniform collection…. [N]ot only were [Conan stories] presented following someone else’s reconstruction of the character’s ‘biography,’ but pastiches of arguable quality (to say the least) were interpolated among Howard’s tales. Further, some of Howard’s own stories were rewritten, other non-Conan Howard tales were artificially transformed into Conan ones, and Conan stories that Howard thought too little of to finish were completed by other writers.”

I love these volumes. Pure Howard, without any later changes or pastiches, given to us as he intended. These volumes led me to Bran, Kane, Kull, El Borak, and more. Howard truly was one of the American masters, and it’s sad (and telling) that the usual suspects denigrate him.

Excellent write-up, HP! There will never be enough Conan/Howard posts to sate my eternal hunger.

I picked up the “The Conan Chronicles: Volume 1: The People of the Black Circle: People of the Black Circle Vol 1 (FANTASY MASTERWORKS) by Howard, Robert E. (2000)”

https://www.amazon.com/Conan-Chronicles-FANTASY-MASTERWORKS-Paperback/dp/B00MF1HCQ2

And vol 2 as well. I’m not enough of an aficionado to know if they are the “best” or “most authentic” version or not, but they are good.

The Mongol-inspired orcs from The Lord of the Rings literally dehumanize barbarians. Barbarians, of whatever sort, are usually explicitly evil or noble savages in traditional fantasy.

The author of the above seems to betray a fundamental misunderstanding of Tolkien. The orcs of Mordor are not in fact barbarians, except perhaps in the same sense as the brutal but highly-advanced “techno-barbarians” of Warhammer 40,000’s ancient Terran wastelands. What they are is the slave-soldiery of a sophisticated, technocratic empire that seeks to overwhelm all the lesser realms in the known world. Ironically, in the few brief glimpses the protagonists catch of them outside of open battle, Tolkien’s orcs display ample evidence that they would very much like to be free-booting barbarians in the mould of Conan, soldiering and thieving and drinking and killing through Middle Earth “with joy and abandon,” and that is perhaps precisely the reason why they are such detestable enemies, and slain without exception or mercy, unlike Sauron’s multifarious human servants.