THROWBACK SF THURSDAY: The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard, Part 3

Thursday , 26, October 2017 Book Review 10 Comments

My blood ran fire when the deed was done;

Now it runs colder than the moon that shone

On shattered fields where dead men lay in heaps

Who could not hear a ravished daughter’s moan.

With All Hallows’ Eve right around the corner, my coverage of The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard draws to a close. You can find my previous posts here and here. This post covers the final third of the book.

So now that I’m done, how does Robert E. Howard’s horror measure up? The first question to ask: measure up to what? I am woefully underread in horror. I would take Robert E. Howard’s horror over the Stephen King I’ve read. But I haven’t read Edgar Alan Poe since high school, and I haven’t read H.P. Lovecraft at all. I read The Turning of the Screw a few years ago, and it bored me to tears.

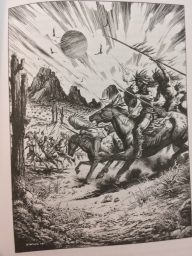

I’m hardly the best judge of horror. It has never grabbed me as a genre. But I did love these stories. I particularly loved Howard’s weird westerns, and the introductions to Solomon Kane and Bran Mak Morn have me excited to grab those collections. None of these alone will supplant Conan for me (yet), but this collection shows Howard undeniably had serious range as a writer.

Once again, the highlights are the weird westerns. There are three in this section of the book—The Man on the Ground, Old Garfield’s Heart, and The Dead Remember—and all three are tremendous yarns. Howard was just much better when he was playing in his sandbox instead of in Lovecraft’s. This section of the book also contains a pretty good barbarian, sword and sorcery story, The House of Arabu. The Hoofed Thing, like Howard’s Conan story Beyond the Black River, gives a prominent role to a heroic dog.

Once again, the highlights are the weird westerns. There are three in this section of the book—The Man on the Ground, Old Garfield’s Heart, and The Dead Remember—and all three are tremendous yarns. Howard was just much better when he was playing in his sandbox instead of in Lovecraft’s. This section of the book also contains a pretty good barbarian, sword and sorcery story, The House of Arabu. The Hoofed Thing, like Howard’s Conan story Beyond the Black River, gives a prominent role to a heroic dog.

In the comments to my first post, Paul Lucas mentioned Black Canaan, a story he characterized as “the most racist short story I have ever read, but also one of the most effective short stories.” I hadn’t read it at the time. As to the first assertion, I can’t agree, even if I only look at stories from this collection. The racial politics are baked into the story, but that will be true of any story set in the rural Deep South in the decades after the Civil War, at least if it is written with any realism. The surface level stuff like social structure and language isn’t jarring.

Much more jarring is the language that Howard uses in some of the earlier stories in the collection—language more likely to reflect Howard’s own views. We see this language even where Howard shows some sympathy toward the African-American character, such as in The Spirit of Tom Molyneaux. It is very in your face. (Although when Howard describes Ace Jessel’s opponent as “the very spirit of the morass of barbarism from which mankind has so tortuously climbed,” we know Howard had complex views towards barbarians.)

But the really troubling attitude comes up in some of his other stories, particularly The Children of the Night. The racism of The Children of the Night isn’t the visceral racism of the rural South, but the erudite racism of well-educated 19th century American sophisticates. The story opens with Kirowan, Conrad, and four others casually discussing skull formation. Pseudo-science like phrenology would power the eugenics movement and be welcomed with open arms by the Progressive movement. Progressive hero Oliver Wendell Holmes would write what might be the most shocking statement ever laid down in a Supreme Court opinion when he rationalized that “three generations of imbeciles is enough” in giving a constitutional OK to forced sterilization of “mental defectives.” We’ve largely memory-holed it, but these were mainstream views—at least among our would-be aristocrats—until the horrors of the Third Reich put a spotlight on the natural end of that particular road.

But the really troubling attitude comes up in some of his other stories, particularly The Children of the Night. The racism of The Children of the Night isn’t the visceral racism of the rural South, but the erudite racism of well-educated 19th century American sophisticates. The story opens with Kirowan, Conrad, and four others casually discussing skull formation. Pseudo-science like phrenology would power the eugenics movement and be welcomed with open arms by the Progressive movement. Progressive hero Oliver Wendell Holmes would write what might be the most shocking statement ever laid down in a Supreme Court opinion when he rationalized that “three generations of imbeciles is enough” in giving a constitutional OK to forced sterilization of “mental defectives.” We’ve largely memory-holed it, but these were mainstream views—at least among our would-be aristocrats—until the horrors of the Third Reich put a spotlight on the natural end of that particular road.

Howard, then, shows not just the prejudices of his geography but also those of his intellectual class.

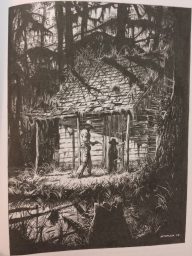

As to Lucas’ latter assertion, I wholeheartedly agree that Black Canaan is tremendously effective. It’s one of the longer stories in the collection, but I blew through it and it felt like quite a short story. Howard is masterful at slowly ratcheting up the tension throughout the tale. The entire thing is delightfully creepy. As Lucas notes, the role of race in the story makes it more effective as horror, not less. This is one reason while I’m leery of efforts to “reimagine” Lovecraft. If you excise the horrific aspect of a horror story, it isn’t really horror unless you add in something else horrific. And I don’t have to have read Lovecraft to think that his work is probably more effective as horror than as fantasy with tentacles.

Stories covered:

The Hoofed Thing

The Noseless Horror

The Dwellers Under the Tomb

An Open Window (poem)

The House of Arabu

The Man on the Ground

Old Garfield’s Heart

Kelly the Conjure-Man

Black Canaan

To a Woman (poem)

One Who Comes at Eventide (poem)

The Haunter of the Ring

Pigeons from Hell

The Dead Remember

The Fire of Asshurbanipal

H.P. is an academic, attorney, and “author” (well, blogger) who will read and write about anything interesting he finds in the used bookstore wherever he happens to be for the moment. He can be found on Twitter @tuesdayreviews and at Every Day Should Be Tuesday.

“This section of the book also contains a pretty good barbarian, sword and sorcery story, The House of Arabu.”

I personally consider THoA to be excellent and rank it equal to several Conan stories. It’s a pity that Howard never did more with Pyrrhas the Argive. He was deeply fascinated by the ancient, pre-Persian Middle East. Far moreso than he ever was by the Greco-Roman period.

I read “Black Canaan” years ago and didn’t registered any racism. It was simply a good story. I’ve reread it lately and only then noticed some attitudes that more progressive people might find objectionable. Well, that’s historical views of particular era I thought. It is still as a good story as I remember.

I don’t feel offended when I read about slavery or serfdom or civil wars. And now, even here in the dark heart of Alt-right I find people worrying how racist old stores can be.

I’m so happy we don’t have American cultural and racial problems.

-

Black Canaan is a case of a story perceived as racist now that probably would have been regarded as racially progressive in Howard’s time. His own views were complex and probably still developing when he died so young. Probably true of Lovecraft as well, which is why it bugs me when people condemn him for stuff he wrote early on that he had changed his mind on before he died.

-

I imagine new and racially improved Lovecraf as saying that browns and blacks have the same right as whites to go mad when R’lyeh rises.

-

How consistent is Howard’s purported racism? Because in my own slow-burn review of his non-Conan work, I keep tripping over counter-examples.

Take “The Noseless Horror” in which the protagonist initially ignores, then suspects Ganra Singh, the cliché Indian manservant of the murder of his host. By the end of the story…well, here, let me quote:

“If you hadn’t showed up just when you did, our bally ships would have been sunk. Ganra Singh, I’ve already apologized for my suspicions; you’re a real man.”

That doesn’t sound like the writing of a white supremacist to me.

-

Howard brings a racist worldview, but still treats people as individuals. (In that, he was no different than a lot of people, including Teddy Roosevelt.) So we repeatedly see strong, developed characters that Howard empathizes with like Ganra Singh or Ace Jessel. Howard was also a fan of introducing characters in an unflattering light and then giving them the opportunity to prove themselves.

Good series, HP. I’m looking forward to reading this volume sometime in the future.

I hope you do Solomon Kane next – he’s my favorite!

-

I do want to read Solomon Kane…but I also want to read Bran Mak Morn…and I still want to read Breckinridge Elkins…so we will see. But something else first, I think. Maybe some other sword and sorcery.

Black Canaan is definitely one of those stories where you need to keep the author’s opinions separate from the protagonist’s. I said it’s the most racist story I have ever read because the protagonist and especially the society are massively racist beyond anything I’ve ever encountered in any other story. For instance, the black people are definitely ‘presented’ as subhumans, but yes, they still did have some dignity. They were oppressed into subjugation/subhumanity rather than being ‘naturally’ subhuman. I was very careful in how I phrased my discussion of this.

That story and how REH created it needed more discussion, and I have just gone into this more on my blog, especially how REH’s mining of psychologically dangerous material affected both himself and the reception of weird fiction.

https://paullucaswriter.wordpress.com/2017/10/27/monsters-from-the-id/

Sorry for hijacking the thread!