To upset the stable, mighty stream of time would probably take an enormous concentration of energy. And it’s not to be expected that a man would get a second chance at life. But an atomic might accomplish both—

Allan Hartley, a dying soldier on a nuclear battlefield closes his eyes, and his life appears to flash before him. But it stops when he’s thirteen, and on the day before the atomic bomb drops in Japan. With all the memories of the future, Allan remembers what also happened on this day, and sets out to change the future–by preventing a murder.

Allan Hartley, a dying soldier on a nuclear battlefield closes his eyes, and his life appears to flash before him. But it stops when he’s thirteen, and on the day before the atomic bomb drops in Japan. With all the memories of the future, Allan remembers what also happened on this day, and sets out to change the future–by preventing a murder.

But Allan also must prove to his father that he is who he says he is, a version of Allan from 1975 with 30 years of life experiences that a thirteen-year-old could never have had.

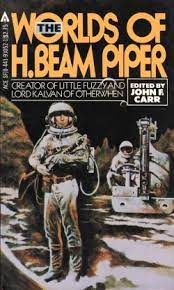

H. Beam Piper started his science fiction career with “Time and Time Again”, joining April 1947’s Astounding roster of A. E. van Vogt, Hal Clement, Henry Kuttner, and C. L. Moore. From this first story, Piper would begin to explore one of the two common fixtures of his fiction: time travel and the historical aftereffects of nuclear war. While he would build longstanding series around each, “Time and Time Again” stands outside the Paratime and Terro-Human History series. However, the 1970s nuclear war that claimed Allan Hartley’s future dovetails nicely with the the 1973 war that created the Terro-Human Future History, of which Little Fuzzy and Space Viking are a part.

The war, however, is just a mechanism to jar Allan back in time, and give him a reason to spend most of the story exploring theories of time travel with his skeptical father. It is curious to see a multiverse idea roundly discarded for something resembling an eternal view of time, where all points might be seen and accessible from any other. But all the exposition on time travel pulls the story down, as it comes after the dramatic conflict of the story–whether Allan is correct about the man he has accused of wanting to kill his wife.

Theory, after all, isn’t as interesting as practice, and while Allan being right goes a long way to helping his father believe him, that doubt needed to linger longer through the conversation instead of being resolved too early. Structurally, the revelation that Allan’s choice is correct should be at the climax and resolution, but that is both a beginners’ mistake and an editorial choice of an editor known to favor theory and conjecture over drama.

“Time and Time Again” is still serviceable science fiction, and a far improvement of the average from that of ten years earlier. Piper’s penchant for space operas have yet to be revealed, but, even in the ending, his characters are men of decisive action rather than navel-gazing theorists. In another magazine besides Astounding, Piper may have received guidance to play towards that strength.

The man who introduced me to the hypnotic pull of military history and one of my favorite authors. Salute, H. Beam Piper!