Tryst in Time: Cosmic Romance

Sunday , 29, September 2019 Authors, Before the Big Three, Fiction, Short Fiction 2 Comments The concept of imaging past lives, reincarnation, wandering egos has been an idea going back over a century in fiction.

The concept of imaging past lives, reincarnation, wandering egos has been an idea going back over a century in fiction.

H. Rider Haggard had the idea of past loves in She (1886). He returned with variations of the idea in The Wanderer’s Necklace (1914), The Ancient Allan (1920), and Allan and the Ice Gods (1927). Edwin L. Arnold had a different life per chapter in Phra the Phoenician (1890).

Edgar Rice Burroughs used the idea in The Eternal Lover in 1914. Jack London’s classic The Star Rover (1915) had episodes of a man in solitary confinement remembering past lives.

The idea had traction into the 1930s. Clark Ashton Smith in “Ubbo Sathla” (1933), Robert E. Howard’s tales of racial memory, and H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Shadow Out of Time” (1936) all used unique variations on the idea.

C. L. Moore’s “Tryst in Time” was in contrast to Howard, Lovecraft, and Smith. All three wrote of personalities traveling through the ages as an exercise in cosmicism. Moore took the cosmic adapted as a romance story. Romance as in love and not adventure.

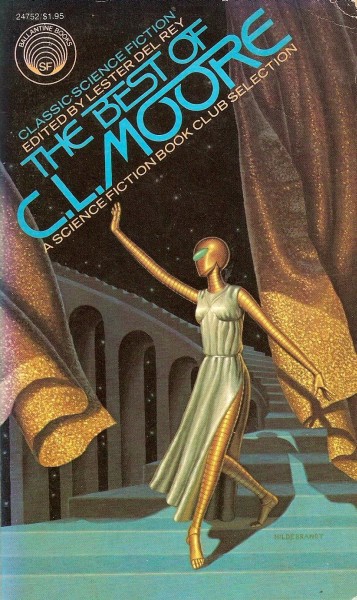

C. L. Moore (1910-1987) had exploded in Weird Tales in 1933 with her story “Shambleau.” She quickly became a favorite of readers of the magazine with her stories of Northwest Smith and Jirel of Joiry. F. Orlin Tremaine was the editor of Astounding Stories and quite willing to purchase fiction from writers normally associated with Weird Tales. Frank Belknap Long and Donald Wandrei both pretty much quit Weird Tales at this time. Astounding Stories paid on timely basis and Tremaine was more consistent as an editor in comparison to the capricious Farnsworth Wright at Weird Tales. C. L. Moore’s first story in Astounding Stories was “The Bright Illusion” in 1934.

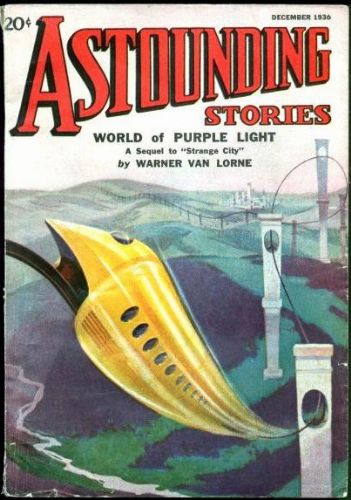

“Tryst in Time” (Astounding Stories, December 1936) was Moore’s third story for that magazine. C. L. Moore liked the bad boys:

“Eric Rosner at twenty had worked his way round the world on cattle boats, killed his first man in a street brawl in Shanghai, escaped a firing squad by a hair-breadth, stowed away on a pole-bound exploring ship. At twenty-five he had lost himself in Siberian wilderness, lead a troop of Tatar bandits, commanded a Chinese regiment, fought in a hundred battles, impartially on either side.”

She describes the scars from tigers, Chinese bullets, Russian “knouts,” and knives of “savage black warriors in African forest” upon “his great Viking like body.” He has a restlessness that was turning to ennui.

“Perhaps, in part, all this was because he had missed love. No girl of all the girls that had kissed him and adored him and wept when he left them had mattered a snap of the fingers to Eric Rosner.”

He develops an “antagonistic friendship” with a scientist, Walter Dow, who argue about true adventure. Dow invents a strap on time travel device. His view is the future is preordained and the past “fixed and unchangeable.”

Rosner first appears in Elizabethan times seeing a beautiful girl with “bright hair.” He moves on with his next stop in a Roman amphitheater, narrowly escaping a thrown spear. He sees a noble woman with “smoke-blue eyes.” The next stop is not given any time but appears to be some forgotten epoch in the ruins of a Cyclopean city. A badly wounded blue-eyed girl appears on the run from beast men. She uses a ray gun on a few of them and then herself. She is the same girl as in Elizabethan and Roman times. The unnamed narrator speculates the girl is “star-born.”

Rosner searches for the girl again finding her in some unnamed period as a captive in manacles of men who a short, hairy, dark, “crooked,” and look like gnomes. Rosner pulls his revolver and rescues the girl, Maia. They escape into the wilderness. She speaks a form of Basque which he happens to know. She leaves him as she is a betrothed to a priest and it is her duty.

He travels to time again to medieval France where he meets a pre-adult Maia. He finds her again this time in England of the witch trials. She is burning at the stake and he mercifully puts a bullet into her.

Oblivion takes him. When he wakes, he is in darkness. A voice speaks to him,

“I have waited so long. . . We have expiated the forgotten sins that kept us apart to the very end. Our troubled reflections upon the river of time sought each other and never wholly met. And we, who should have been time’s masters, struggled in the changing currents and knew only that everything was wrong with us, who did not know each other.”

A hand takes his and they step forward together.

I have never read a romance story or novel. Is the dialog like this? C. L. Moore mentioned in a letter in 1936 that she was attempting to write a story for the love pulps.

Moore is hazy on the time periods with her boiler place high medieval imagery she used in the Jirel stories along with some vague hints of alien humans in the distant past.

“Tryst in Time” is at its heart a romance story with science fiction trappings. It amazes me that Moore is (or was) held up as a science fiction icon. Was “Tryst in Time” conveniently memory holed? Just remember that your adventurer will develop ennui if he fails to find love.

Moore never claimed to be some badass chick or a riot grrrl. Rosner sounds like quite the bad boy,

“The Time Traveller” is at its heart a romance story with science fiction trappings. It amazes me that Wells is (or was) held up as a science fiction icon.