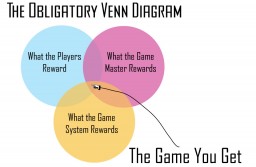

In my post last week, I posted up this Venn diagram, which is part of my philosophy about game design. While there are proponents of several models of how RPGs work, including the three-fold model, the actor-response model and the “story model,” I look at roleplaying games as the intersection of three different reward mechanisms. The game you get is the place where those rewards overlap and compete with each other.

In my post last week, I posted up this Venn diagram, which is part of my philosophy about game design. While there are proponents of several models of how RPGs work, including the three-fold model, the actor-response model and the “story model,” I look at roleplaying games as the intersection of three different reward mechanisms. The game you get is the place where those rewards overlap and compete with each other.

Those three reward mechanisms are what the rule system rewards, what the game master rewards, and what your fellow players reward.

Those three reward mechanisms are what the rule system rewards, what the game master rewards, and what your fellow players reward.

Rule system rewards are the easiest to quantify: If a rule system says that taking an ability X is useful in circumstance Y, players who take ability X are going to seek out as many opportunities as possible to get into circumstance Y. The “advantage” and “disadvantage” rules in games from Champions onwards are examples of this kind of reward as applied to character creation, and as my essay last week pointed out, proved to be publishing gold mine for RPG publishers: Books with character creation and optimization options sell to a much larger percentage of the player base of a game.

Other rule system rewards include how treasure and the material rewards of adventuring are divvied out. One of the greatly underappreciated rules of Basic Dungeons & Dragons was tying the gold recovered from adventuring to the character’s advancement and giving it priority over what they killed.

Game master rewards are part of the social contract. At their most basic level, it’s the choice of adventures and setting the challenges. If your game master likes running games of political intrigue, political intrigue will be rewarded. If your game master likes running kick-in-the-door-murder-and-loot, home invasion and looting will be rewarded in the game.

A subtler form of game master reward is signalling behavior. If you’ve ever played a game where the same six skills keep coming up, that’s the game master making a reward out of a common set of tropes and mechanics. Sometimes, this is just lazy game mastering, and sometimes it’s unquestioned assumptions. In “Old School” play styles, where much of the world is based on the game master “fairly” interpreting circumstances and filling in the gaps, game master rewards tend to trump system rewards. This is one source of the nostalgia many players have for the days when systems didn’t offer much that was nailed down, and being clever at the table was worth more than your “build.”

Player reward mechanisms have always been present. Sometimes, it’s the roleplaying itself. Everyone who’s played in the hobby enough to want to keep at it has memories of sessions where the party never picked up dice, but talked in character with each other for hours. In Finland and Scandanavia, this led to what’s called Nordic LARP. Many newer games, such as Robin Laws’ Dramasystem or Vince Baker’s Apocalypse World (and the wonderful hack of Apocalypse World covering D&D tropes, Dungeon World) all have mechanisms where other players determine some of the rewards of the game, in a more purely mechanical context.

If you look at games as reward mechanisms for certain types of behaviors, emergent properties become evident. Systemic rewards have an emergent property of perceived fairness. I say that this fairness is perceptual only – everyone has played games where an option was significantly better than the others available in the game. Most people who’ve sat at a roleplaying game table have also seen games that have been derailed by “Well, the rules don’t say I can’t do it…” when a player’s vision of how the fiction of the game differs from the game master’s or the other players.

Game master rewards also have some emergent effects – the game master is usually the final form of appeal on rules and setting disputes. Some games – Old School style D&D for example – pretty much require that the game master rewards be more important than the systemic rewards. The downside of over-reliance on game master rewards is that the game often devolves into “who’s best at buttering up the GM?” I’ve seen more than a few game groups fracture over perceived favoritism by the game master.

Player reward behavior often acts as a counter-pressure, or diffusion, of the “butter up the GM” parts of roleplaying games. They’re also comparatively new – they’ve only been widely used for a decade or so, and they tie into the third epoch of roleplaying games in my last post: When your game focuses on inter-character relationships as a source of conflict, drama and “powering up”, the players need to have a say in who gets rewarded for what. Useful game mechanics include Sorcerer‘s system of handing out by player acclamation. I’ve used this myself with Minimus, where describing a failure can get a player nominated for a bennie – a situational bonus to roll twice and take the better result. Cartoon Action Hour has a similar mechanic.

At their current state of development, mechanical support for player rewards are heavy handed. It is easy for players to chase after die roll modifiers with pro-forma sketch-behavior meant to trigger the rewards. This is a beautiful example of playing the rules, not the game, and isn’t an indictment of the rules so much as it’s recognizing a mismatch between a player’s style of play and a given rule set.

When looking at specific games, realize that the sizes of those three circles will vary depending on the game. GURPS, and to a lesser extent the d20 engine’s games and descendants, are all about the systemic rewards. The game rules are meant to be a bedrock of fictional (or fairly realistic) physics, with the GM acting as a guiding hand, and player rewards largely limited to roleplaying opportunities. Some of the other games I’ve mentioned here have much smaller circles for systemic rewards and larger ones for player rewards or game master rewards.

Even different editions of the same game can have significant variation – imagine how that diagram would look – and where the relative area of overlap is – for each of the different editions of D&D from Moldvay BECMI through to 5th edition. While I’m much more of a fan of player-reward driven games, I’m aware that this is far from the only way to play, and that tastes matter. I’m also aware that there are several different play styles, and different types of players, and you really can’t make a roleplaying group out of only one or two types of players, you need the entire taxonomy.

Which may make an interesting topic for a future post…

What I missed for a long time were the old “build a wizard’s tower” rewards, where once you achieved a certain rank, your quest to gather the men and materials and land to establish a keep pretty much became the driving impetus for a campaign.

The only time I actually played a campaign through to the completion of a wizards tower (or keep of any sort!) was as a party member (not the obsessive high-level Magic User bent on getting his tower and necessary spell components), but it was thoroughly satisfying.

In fact I’d say it was the best end to any long-running campaign I ever participated in…except that the actual ending of that campaign was even better. Soon after the ribbon cutting, one of our other guys in the party accidentally blew the entire thing–and the party– up with a thermonuclear bomb he’d been unwittingly toting around.

I would usually award points for overcoming a challenge, however it was done. So, you could kill the threat, sneak past it, or reason with it. Whatever worked. The more players are encouraged to think outside the box and be creative, the more fun I had as a dungeon-master. I got to the point of wondering “what will they do next?”. Tactically, This made encounter design more fun: what will the monsters/opposition likely do? Will the players be able to surprise me? I always made sure there was at least one way to win/succeed, but was willing to accept other logical outcomes.

Then, there was 4th Edition, which killed role-playing altogether. Set, inflexible encounters are OK for video games, but don’t expect a paper game to compete with a video game unless there is more flexibility, role playing or something else.