The war lords and bandits of Western China thought all visitors were fair game—until they ran into Norcross and his hard-boiled black army from the American Expeditionary Forces.

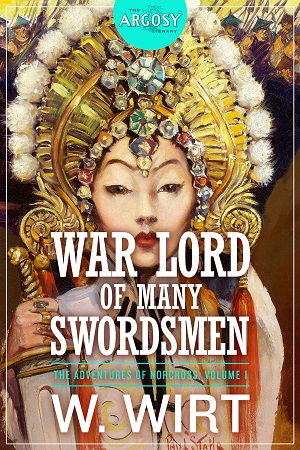

Starting in 2015, Altus Press has rereleased the stories that filled the first and the greatest of pulps, Argosy Magazine, with its Argosy Library line. With over thirty volumes, stories by well-known pulpsters such Lester Dent, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Otis Adelbert Kline, Max Brand, and Abraham Merritt have returned to print for the first time in years. Alongside these more familiar authors, Altus has introduced new generations of readers to George F. Worts, Loring Brent, Victor Rousseau, and many, many others, drawing from 96 years of pulp adventures and packaging them with the gorgeous covers from the pulp age. And it was the striking painting of a Manchu princess standing in front of her army that drew my attention to War Lord of Many Swordsmen, the first collection of the adventures of John Norcross by chinoiserie enthusiast and former lawman W. Wirt. Within its pages are two short novels detailing the adventures of Norcross, his infantry company of black soldiers, and his adopted sister, Princess Ch’engyuan.

The first adventure, “War Lord of Many Swordsmen”, interrupts Norcross’s pursuit of a legendary lost Zulu impi regiment into China. A wealthy donor hires his company of black WWI veterans to retrieve a sealed cylinder from a Chinese fortress city. Along the way, they rescue the exiled Princess Ch’engyuan and her betrothed, formerly of the same fortress city where Norcross’s treasure lies, ousted by a warlord supported by the same Russian and British spies sent to frustrate Norcross’s mission. Ch’engyuan and Norcross forge an alliance. He will help liberate her city and she will help him find the cylinder. But before they can reach Ch’engyuan’s city, Norcross’s company must first march through the Chinese hinterlands, with Russian Cossacks, Manchu bandits, and the Zulu impis barring his way.

Let’s start with the elephant in the room. Racism. The second most common accusation used to dismiss the pulps. Frankly, if you’re the type of person that the language of Huckleberry Finn and Mark Twain sends to fainting couches, “War Lord of Many Swordsmen” is not going to change your mind. Wirt uses the dialects of his time, including those now deemed too controversial for some schools. But, if like an adult, you determine a person’s character by their actions instead of their words, you will be pleasantly surprised. Norcross’s company is elite, expert with their weapons and their dress, and lack the sad sacks, shirkers, and blue falcon dregs that afflict many a regiment. They are professional, disciplined, proud, and almost gleeful killers who show initiative in the absence of orders. They are proper fighting-men who have beaten the best that the Germans, the Zulus, and the Manchu have thrown at them. Wirt never indulges in the casual colonial racism of black soldiers being inferior to whites, the white man’s burden, or the even more dismissive need for white officers to make non-white soldiers fight. The white officers are Irish, Germans, and Jews, the least welcome of European ethnic groups in WWI American society, sometimes even less so than blacks. In short, Norcross’s soldiers, black and white, are formidable men and are given the respect due their prowess. And their foes–renegade Zulu impis, Cossack horsemen, and Manchu war lords–are fearsome opponents worthy of such men. The inevitable vices of the villains are those common to all men, not to any one race. And while Ch’engyuan and Norcross indulge in a bit of culture clash between America and Manchu, neither is seen as superior to the other.

I suspect that the almost chessboard fairness of the story is designed. “War Lord” was written in the years after Charlie Chan, when writers started intentionally creating characters and stories to counter the blatant racism of the Yellow Peril. And the forces arrayed against each other are near peers. The machinations of the British Katherine Dudley are set against the efforts of the Anglo-Saxon John Norcross. The black AEF troopers stand against the Zulu impis. Manchu warlord squares off against Manchu warlord. Miss Dudley even serves as the counterpart to Princess Ch’engyuan. The forces are almost equally arrayed, although Norcross’s side still suffers the numerical disadvantage. But this parity of races and sexes is not used to turn the story of a crack company of American veterans sent to retrieve a special device from the backwater of China into a social sermon. This chinoiserie is built on the thrill of the exotic, and black machine gunners and Zulu impi, Chinese princesses and British spies, and Cossack chieftains against American officers make this round of the Great Game stand apart from the Indian and Afghan trappings of the genre.

A story like this lives and dies by the adventure. This short novel affords little time to develop the cast beyond Norcross and Ch’engyuan with more than a line of description and a unique–and usually grating on the page–dialect. Instead, Norcross and his troops march from challenge to challenge in pursuit of a sealed metal tube hidden in China, encountering the exotic and strange along the way. And there’s nothing stranger than an improbable remnant of the shattered Zulu nation camping in the Chinese mountains–except the contents of the sealed tube. Towards the end, misdirection and machination add variety to the campaign, providing a change in pace from the constant chivvying the AEF soldiers endure. The story is proto-military fiction, from before the days where beans, bullets, and tactics tied up the description in the story, and it would take little to update this into something akin to Rogue Warrior and its many copycats. Drawn out to a longer length, the double time cadence of battle and exotic discovery would grow tedious, but the shorter length ensures that the adventure wraps up before it wears out its welcome.

All in all, “War Lord of Many Swordsmen” is a fine example of an adventure pulp and one that challenges the common assumptions of racism surrounding the pulps. It is unfortunate that the science fiction boom at the end of the pulps overshadowed adventures like these. Fortunately, the Argosy Library now offers enthusiasts a chance to rediscover one of the most popular genres of pulp fiction.

Thanks for the review, Nathan! I’d been wondering about this. Altus is putting out some great reprints.

Interesting. I have never heard of Wirt, but everything you have to say about him makes me want to check him out.